Searching for Elizabeth Gould in the Archives of the Mitchell Library

‘Who was Elizabeth Gould (1804-1841), and why has her name now been elevated to equal status with that of John Gould?’ wonders Roselyn Russell (2009: 1), author of the recent biography The Business of Nature: John Gould and Australia (2011). While the taxonomist and natural history publisher John Gould is often regarded as the ‘father’ of Australian ornithology, having scientifically described almost two hundred new Australian species (Datta: 151), the important contributions made by his wife and principal artist, Elizabeth Gould, are less-well remembered. In 1838 the London-based zoological team travelled to Australia to collect and draw specimens for the seven volume publication, The Birds of Australia (1840-1848). The couple brought along their eldest son, John Henry, but left their three youngest children in London, in the care of Elizabeth’s mother and cousin. Residing in Hobart and the Hunter Valley, the Goulds spent almost two years in Australia, returning to London in 1840 with their hoard of sketches, field notes and study skins. Unfortunately, Elizabeth enjoyed only one year back in England designing and producing hand-painted lithographs for The Birds of Australia. She had completed 84 of the collection’s 681 plates, when she succumbed to puerperal fever in August, 1841, just four days after the birth of her eighth (surviving) child. She was thirty-seven.

Elizabeth Gould’s intriguing biography, her courage in leaving her children to participate in a scientific expedition, the controversy surrounding her contributions to the lithographic plates she co-authored with her husband, and her early death, demonstrated great potential for the explorations of historical fiction. However, eighteen months into my creative dissertation, a fictional memoir titled, Elizabeth Gould: A Natural History, I was yet to be convinced by Russell’s assertion that the zoological illustrator’s reputation had been significantly elevated. I had undertaken an extensive amount of research: a handful of biographies of John Gould, two volumes of published correspondence, numerous studies of his zoological works, along with histories of ornithology and lithographic print-making. I familiarised myself with Elizabeth Gould’s drawing and painting style, viewing many of the 600 lithographs she designed and produced during her eleven year career. To learn more about Australia’s bird species, I took walks with bird-watchers and became a volunteer taxidermist, making study skins of native birds at the Queensland Museum.

Elizabeth Gould (nee Coxen) was born in 1804, in Ramsgate, Kent (Chisholm: 1). Her father held a military posting with the British navy. She married John Gould in her mid-twenties and soon after began drawing and painting for him, illustrating the novelty bird species that turned up among the caches of specimens he taxidermied for clients. In 1830, when John Gould made the decision to produce and publish a subscriber-paid volume of hand-painted lithographs of Indian birds, Elizabeth Gould served as principal artist. Biographical legend has it that when John shared the inspiration for his publishing adventure with Elizabeth, she was incredulous, asking who would do the work of transferring the images onto stone (Bowlder Sharpe: xii). John, who did not possess the skills of fine drawing, uttered his infamous reply: ‘Why you, of course’ (Bowlder Sharpe: xii).

Before reaching the age of thirty, Elizabeth had designed and illustrated eighty hand-coloured lithographs, representing one hundred species of Indian birds, the majority of which were not previously known to science. In 1832, the plates, published at quarterly intervals in issues of twenty, were bound together under the Goulds’ first title, A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains. To reward Elizabeth’s achievement in creating the lithographed plates, the systematist, N.A. Vigors, who had assisted John Gould with the collection’s taxonomy, named a species of sunbird after her, Mrs Gould’s Sunbird, Aethopyga gouldiae. Elizabeth collaborated with her husband until her death, creating designs, drawings and lithographs for eight separate publications, including The Birds of Europe (1832-7) and monographs on the Toucan (1833-5) and the Trogon (1835-8) families. Elizabeth illustrated the avian specimens that Charles Darwin’s collected during his voyage of discovery on HMS Beagle and three collections that described Australian species. To acknowledge Elizabeth’s contributions to Australian ornithology, John Gould named the Gouldian Finch, Erythrura gouldiae, in her honour.

At the bottom of each plate in the Goulds’ first publication, A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains, is the artist’s signature, ‘Drawn from Nature and On Stone by E Gould.’ ‘Drawn from nature’ indicates that the species depicted had been taken from the study of a taxidermied specimen. This was to distinguish it from an image that was a copy of another illustration and therefore considered inferior. When plates for the Goulds’ second book, The Birds of Europe (1832-1837), were released, a significant change was evident in the bottom left-hand corner of each plate. Rather than acknowledging Elizabeth as the artist responsible for designing and colouring the lithographs, a new signature appeared, ‘J & E Gould del et lith,’ suggesting joint authorship in the form of a husband and wife collaboration. ‘Del’ referred to the practice of delineation, or the artistic composition of the drawing, and ‘lith’ to transferring the design onto limestone during the process of lithographic printmaking. In all subsequent volumes that John and Elizabeth Gould worked upon, plate authorship was recorded as a combined effort, even though it was commonly accepted that John Gould was an ornithologist, taxidermist, book-producer and businessman, not a visual artist (Jackson: 39). Rather than elevating Elizabeth’s significance as Gould’s principal artist, this arrangement obfuscated her artistic contributions for the next 170 years.

This shift in authorship intrigued me, and I was sure that it had impacted upon John and Elizabeth Gould’s working and intimate relationship. By this time I was struggling to continue with my first draft of the fictional memoir. In my anxiety to familiarise myself with the Goulds’ biography, I had become distracted by the myriad detail of bird lists, painting supplies, research expeditions, and publication deadlines. The more I delved into the archive, the more overwhelmed I felt by information and data, losing the focus of story and narrative. Unable to make progress with a chapter, I would compile lists, copying the working approach of John Gould. I created files in which I cross-referenced dates referring to Elizabeth’s pregnancies; I collected the names of each species designed and lithographed by her; I inventoried each Australian species John Gould described; I listed his collecting trips and the dates and the order of publication of plates in The Birds of Australia.

I wondered if viewing physical artefacts used by Elizabeth and John Gould might help reconnect me with the process of characterising Elizabeth as my point-of-view narrator. In my obsessive research, I had lost touch with the spark that urged me to explore the artist and mother’s hidden legacy. I decided to visit the Mitchell Library in Sydney, the repository of the largest collection of Gouldian material in Australia. The library’s archive includes original drawings, paintings, designs, templates, hand-coloured lithographs, field journals, correspondence and diaries.

In conducting my trip I hoped to achieve a number of aims. Primarily, I wished to discover a kernel or two about Elizabeth Gould’s habits and temperament by examining personal effects that had survived her. I hoped this contact would help me to channel the historical persona into the character I needed to produce for the page. I also wanted to train my eye to recognise Elizabeth Gould’s artistic ‘hand.’ And lastly, I sought answers to questions raised during my research into the collaboration in plate-design between Elizabeth and John Gould. For I was yet to find a single example of John Gould’s major contribution to lithographic plate design during the period Elizabeth worked as principal artist in his production house. Contrary to Russell’s assertions, from my investigations it seemed that John Gould’s standing in Australian ornithology and as a zoological illustrator had been preserved and even enhanced during the last several years. Since embarking on my dissertation, three new books exploring his life and works had appeared in the natural history book market. Conversely, Elizabeth Gould’s reputation had suffered the opposite effects, her importance as a lithographic artist not only obscured and forgotten, but her original works often attributed to her husband.

Elizabeth Gould’s plant album

I am during his absence drawing as many native plants as I can, I mean branches of trees, some of which are very pretty. (Sauer: 6)

I find amusement and employment in drawing some of the plants of the colony, which will help to render the work on Birds of Australia more interesting. (Sauer: 13)

I typed ‘Elizabeth Gould’ into the search aid Trove’s ‘pictures, photos and objects’ database, and seven links were returned. John Gould’s name elicited around 577. This was how I discovered ‘Elizabeth Gould’s plant album’, a collection of 76 drawings, paintings and sketches of plants, flowers, and occasional birds, created during her stay in Australia. The album was acquired by the Mitchell Library in the 1950s–it had been twice previously offered for purchase in the 1930s by the auction house Sothern. The plant album had been digitised by the library and before making my trip, I familiarised myself with the contents: hand-coloured fronds of acacias, eucalypts, casuarinas, native grasses and even a crimson Tasmanian waratah. Interestingly, a significant number of the backgrounds of the plates for The Birds of Australia showed plant and flower detail that was identical to the studies in Elizabeth’s plant album. Foliage, branch, gumnut, and flowering bud had been copied directly onto sketch paper and a thornbill, honeyeater, parrot or wren drawn perched on a branch, its diagnostic characteristics revealed by an appropriate parting of leaf and stem.

In my early reading about Elizabeth Gould, I’d encountered references to her described as a talented botanical artist with a background in flower painting and landscapes (McEvey 1973: 22). I had been unable to find any information about Elizabeth’s training in botanical drawing–Edward Lear claimed to have assisted with the foregrounds she painted on A Century of Birds for the Himalaya Mountains–and wondered if the plant album provided the source for these comments (Jackson: 35). While this was an interesting proposition, I had other reasons for subjecting the originals to a thorough examination. One of my ideas was to investigate the album for evidence that Elizabeth Gould made original contributions to The Birds of Australia, and did not merely act as handmaiden or studio copyist to the vision of John Gould, as suggested by art historian Allan McEvey (1967-68: 16). Eighteen months’ research had left me deeply unsettled by McEvey’s assertion that John Gould was the ‘guiding spirit’ behind all of the plates that bore his initial (1967-68: 16).To frame my research, I trained my focus on elements in the Gouldian ‘house’ style that might be attributed to innovations by Elizabeth Gould.

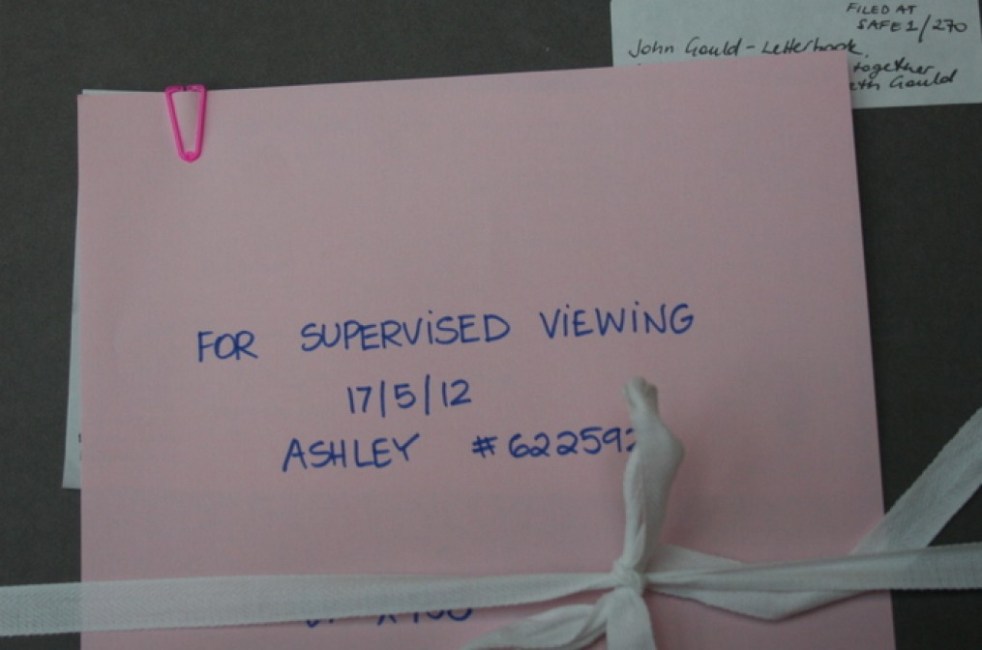

To view the album, a member of staff escorted me into an open-plan office space. My conditions of access were supervised and I was provided with various-sized magnifying glasses to decipher the album’s faded signatures, dates and marginal notes. On some pages there was a signature, ‘EG,’ ‘E Gould,’ on others, a few lines of handwriting recording collection details, a date and a place, ‘Yarrundi, May 1839’, or just simply the botanical name of the sketched plant. One interesting observation was that many of the drawings, especially the folio-sized images, were soiled, marked by what seemed like an oily, dirt-attracting substance that I thought might be lithographic crayon grime. This heavy use seemed evidence that the paintings were especially important to John Gould. Not only had the watercolours been preserved, they had been repeatedly consulted as references. Had they become a sort of template, I wondered, that John Gould and H. C. Richter, the artist he employed to replace Elizabeth, consulted during plate composition across the eight year production schedule of The Birds of Australia? Several of the drawings were torn and repaired, corners were missing and where inferior paper had been used substantial foxing had taken place. The drawings were made on different sizes and grades of paper, including Royal folio with watercolour markings, the smaller octavo, and the backs of recycled lithographs. What hadn’t captured my attention during my digital viewing of the record–but was obvious in the originals–was that in many of the sketches only the top leaves, buds and flowers of the plant specimens had been finished in watercolour wash, the lower branches and foliage left in pencil outline. It was as if Elizabeth had attempted to record as many native Australian botanicals as possible, for example, she made numerous studies of the densely-flowering acacia genus, but was time-poor and had to rush.

As part of my practical research I observed a wild Mistletoebird through binoculars; I cradled a taxidermied study specimen in my palms. I remember my awe at the diminutiveness of this tiny creature, no bigger than an elephant beetle, entombed in its moulded cube of museum Styrofoam. While I’d been casually watching birds for about a decade, it was only in the last few years that I’d become serious about identifying new species. It wasn’t until August, 2011, during a trip to the Wildlife Conservancy property Bowra Station, about twenty kilometres north-west of Cunnamulla, that I had first encountered the species. I’d tried to find it closer to home, but not been successful, though it resides wherever mistletoe occurs, maintaining a symbiotic relationship with the plant by dispersing its seeds in its droppings. As is sometimes the case with a newly observed species, I have since seen it several times. But there was something about my initial sighting of this energetic creature, chirping and flitting about, sharing its mistletoe home with a Singing Honeyeater, that gave me a quiet thrill. The adult has a diagnostic black stripe running down the middle of its underside, which helps distinguish it from the Scarlet Honeyeater, another miniscule red and black species that darts about at neck-craning heights. The Mistletoebird’s scarlet throat and chest plumage bleed at the mid-line into a white belly; its back, rump, tail and wings are glossy black.

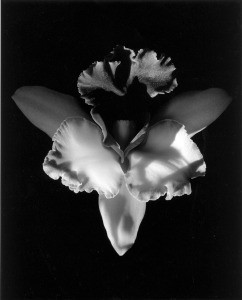

On plate twenty-one of the plant album I found Elizabeth Gould’s 1839 sketch of the Mistletoebird. The background foliage of a branch of casuarina, draped in flowering mistletoe and supporting a hammock-shaped nest, included a juvenile’s head just visible at the opening. The nest’s outer casting of spiders’ web, dried lichens and leaves had been figured with precise clean pencil strokes. This original drawing was sketched by Elizabeth at her brother, Stephen Coxen’s farm, ‘Yarrundi’, near present-day Scone. The species, a member of the flowerpecker family, isn’t endemic to Australia, and nor was John Gould the first to scientifically describe its morphology and habits. Most pertinent to my investigations, was that the unpublished sketch had become the design for the Misteltoebird plate in The Birds of Australia. Few details were changed. The pencil-sketched birds were invigorated with their plumage colours and diagnostic markings, the nest given its appropriate shadings and tones. McEvey, who confessed to twenty-years of puzzling over John Gould’s drawing ability, made the following comment about the occasional bird sketching in Elizabeth’s plant album:

Pencilled bird drawings are sharp and precise in their details showing feather groupings, and are quite different in character from Gould’s rough sketches [in the present illustrations]. (1967-68: 21)

If McEvey’s observations are correct, then the sketch provides documentary evidence that Elizabeth Gould was an original artist in her own right. She compiled studies for and then finalised–‘delineated’–the composition, tracing it onto the limestone printing block and selecting the paints and colours for the hand-coloured plate. While John Gould must have approved the image, does this gesture deserve the ‘delineation and lithography’ credit recorded on the bottom left hand corner of the plate?

That Elizabeth Gould’s plant album contained Australian birds perched on native Australian botanicals was also noteworthy because the depiction of the relationship between a bird species and the plants it foraged on or nested in was a deviation from early nineteenth century conventions of zoological illustration (Jackson: 16). Foliage generally worked like parsley garnishing a tray of sausages, a de-emphasised backdrop to the horn-shaped bills and streaming plumages of the novel bird specimens arriving at London’s docks from around the world. The field observations that accompanied specimens were inconsistent in their accuracy and attention to detail and thus of questionable scientific usefulness (Farber: 47). In their early works the Goulds’ were inspired by Edward Lear’s ground-breaking monograph, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots: the greater part of them species hitherto unfigured (1830-1832). Lear was a pioneer of natural history lithography, providing minimal plant details in the backgrounds of his bird lithographs to better showcase the texture and colours in his exotic subjects’ plumages (Jackson: 35). The backgrounds in the Goulds’ first collections paid scant attention to botanical detail, the generic foliage serving to highlight the features of the illustrated bird. It was a case of aesthetics trumping science.

Upon returning to England, John Gould, who had trained as a landscape gardener, offered the plant specimens that he and Elizabeth collected in Australia for sale, but they were passed over for being improperly referenced and preserved. This was ironic, given that in Gould’s own field of Zoology, improper handling, preparation and storage of specimens could result in the contagion of whole collections by mildew and insect infestation. Considering Elizabeth’s curiosity and enthusiasm about Australian native plants, and John’s lack of care, the question might be raised as to whose idea it was to depict the bird specimens in The Birds of Australia perched on the native species they nested in and foraged upon. Is it possible that Elizabeth Gould contributed to this important development in the Gould ‘house’ style?

As I closed the album and handed it back to its librarian-guardian, I felt close to my subject. The folio was an artistic repository of grief and what ifs with respect to Elizabeth Gould’s cultural reception. What might be her current reputation, I wondered, had she survived the birth of her eighth child and completed illustrating the plates for The Birds of Australia? I sensed, shearing in close, John Gould’s tragic loss of his beloved wife and principal illustrator. He had kept all of these bits and scraps of half-finished watercolours in a special album. He had consulted them time and again, studying them, touching them, laying them out in the studio for his new artist, H. C. Richter, to absorb. He had understood his deceased wife’s discovery in including sketches of native Australian plants, ‘rendering the works on [The] Birds of Australia more interesting’, as she put it in a letter to her mother (Sauer: 13).

‘Pattern plates’ for The Birds of Australia

One of the most important Gouldian records I travelled to the Mitchell Library to view were the ‘pattern plates’ for The Birds of Australia. The pattern plates were the original water-colour templates prepared by John Gould’s artists, Elizabeth Gould and H. C. Richter, for the colourists to hand-colour multiple copies of the lithographic impression and are regarded as one of the Mitchell Library’s treasures. To put the pattern plates into a financial context, in 2011, a complete edition of The Birds of Australia–seven volumes comprising 683 hand-coloured lithographs and accompanying letterpress–sold at auction for $230,000 (Collector Chat: 3).

Desiring a deeper connection with my subject, this record felt more significant than an original hand-coloured folio edition of The Birds of Australia, not to mention the digitalised JPGs of plates collected in my laptop’s hard drive. The pigments on the template lithographs had been selected and applied by Elizabeth’s sable brushes. However, the appearance of John Gould’s pattern plates was not what I had been expecting. I had imagined the record as a couple of large volumes, roughly bound together, a haphazard collection of what had been salvaged of the original 681 watercolour templates. Near the beak or foot of a honeyeater or rosella there would be inked instructions. On this latter point, my expectations were confirmed; some corners and edges of the plates contained marginalia in faded brown ink, corrections for the head colourist, Gabriel Bayfield, to pass on to his workshop: ‘feet rather too blue, and ‘a little warmer in the grey’. But my other anticipations were off the mark. The pattern plates for The Birds of Australia were bound in hand-tooled green Morocco leather, embossed with gold lettering on the spine and front, the binding John Gould recommended for his finished volumes. The record so accurately resembled the published folio that I experienced a moment of awful panic and rechecked the title on the spine, sure that I’d been given The Birds of Australia to browse rather than the record requested. The pattern plates were bound in taxonomic order, in identical sequence to The Birds of Australia, each illustrated lithograph accompanied by letterpress detailing the date and name of the ornithologist who first described the species, the scientific and common names, field observations regarding behaviour, distribution and the rearing of young, and plumage descriptions, all of the text prepared by John Gould.

Before her death, Elizabeth designed and lithographed nine of the ten templates of fairy wrens depicted in The Birds of Australia. In the Goulds’ era, members of the endemic Australian genus was known as warblers and considered ‘allies’ or distant relatives–according to the pre-Darwinian quinary system of taxonomy used by John Gould–of morphologically similar European song-birds. Their wide distribution, brightly-plumaged males, human-curious behaviour and co-operative breeding practices led to popular interest in the genus, which continues into the present. When the Goulds visited Australia, it was not just to collect bird specimens that they could taxidermy, mount and draw; John Gould was also concerned with obtaining field information using his own expert observation. He instructed his collectors to bring him the species’ clutches (eggs and nests). In the letterpress that accompanies the Blue Warbler (Superb Fairy-wren) plate, which depicts three subjects, a male in display and a female attending a juvenile in its nest, the field observations are as valid today as they were almost two hundred years ago. The dominant male shows full colour plumage only during breeding season, the species is socially gregarious, practicing co-operative breeding, and they incubate the eggs and rear the young of the Bronze Cuckoo parasite. Excluding the Superb Fairy-wren’s behaviour toward cuckoo eggs, all of these discoveries are depicted in the narrative of Elizabeth’s drawing. Her artistic observations of the species while they were out and about gathering food and nesting materials, showing their communication with one another, capturing their moving silhouette–a combination of diagnostic features, known in the birding world as a species’ ‘jizz’–are all evident in her meticulous lithograph. Any bird-enthusiast can immediately appreciate the tenderness, accuracy and care shown in Elizabeth’s depictions of this well-loved species.

Could it be that Elizabeth’s first-hand studies of fairy wrens influenced her drawing and composition in new and positive ways? There are certainly significant differences between the nine templates Elizabeth delineated and lithographed of the genus Malurus and the pattern plate of the Malurus pulcherriums, the Blue-breasted Fairy Wren, first described by John Gould in 1844, three years after Elizabeth’s death. The species was delineated and lithographed for The Birds of Australia by John Gould and H. C. Richter. Richter, who had not observed any species of fairy wren alive or in its natural habitat, resorted to block colour on the head and crown, failing to define the feather detail on the cheek, crown, ear-coverts, throat and forehead. Conversely, Elizabeth went to extraordinary lengths, with what must have been a single-haired brush, to show the barbs in each individual feather. This attention to detail is present in her depiction of eye-rings, bristles around the bill, and in the texture of the skin of the lower legs. Richter’s Blue-breasted Fairy Wren, when compared with Elizabeth’s Variegated, Red-backed, Splendid and White-winged Fairy Wren lithographs, lacks tone, depth and fineness.

Elizabeth Gould paid careful attention in colouring her Australian species, using a soft pallet of matt watercolours, nothing garish or overly bright, clumsy and unrefined. She deployed an array of painting tools and brushes for outlining the most minute detail, for example the scalloped edges of the breast feathers of her pale-headed rosella, and the scaly skin of her brush turkey’s feet. Other effects of Elizabeth’s fine technique include the light-reflecting finish she created to suggest the eye’s rounded orb, giving it a lifelike gleam, and detailing the tiny hairs on honeyeaters’ brush-like tongues. Some of the lithographs signed ‘J Gould and H C Richter’ show inaccuracies and infelicities in colour representation–vague and over-zealous application of black, and gaudy yellows, reds, and oranges. For example, in the drawings John Gould prepared for the Corivd family–crows, magpies and butcher-birds–there are issues with form and movement. A recurring inaccuracy occurs in the shape of the subjects’ heads and crowns, particularly if positioned with the neck at an unusual angle. The lack of tone built into the colouring may be responsible for the ‘flat’ rather than spherical rendering of the heads in several lithographs. It’s almost as if the pattern plate had been sent to the colourists before the last layers of tints and tones were added to complete the design.

Is it possible that Richter, who like Edward Lear, was eighteen when he began to work for John Gould, gave in to pressure to meet deadlines and rushed the templates he prepared for Mr Bayfield’s colouring workshop. While John Gould placed Elizabeth under immense constraints, improvements to her style and developments in her technique continued throughout her brief career. In The Birds of Australia, Elizabeth’s illustrative abilities reached their zenith, shown in such magnificent plates as the Satin Bowerbird, the Mallee Fowl, the Superb Lyrebird, as well as her wrens, rosellas and grass parrots, or, as they were known in the nineteenth century, splendid, beautiful and elegant grass parakeets.

Elizabeth Gould’s letters and diary

I also visited the Mitchell Library to view Elizabeth’s letters home to her mother and cousin, and the diary she kept while travelling in New South Wales. If it wasn’t for the persistence of Alec Chisholm, a journalist and amateur ornithologist, who visited Elizabeth Gould’s English descendants in the 1930s and uncovered fourteen letters and the diary, little of the thoughts, feelings, experiences and opinions of this pioneering lithographer would be known. In my search for a material connection with Elizabeth Gould, I discovered that she used every square inch of her correspondence paper. Paper, made from rags and imported from France, was a precious resource in the late 1830s. The Goulds brought many forms out to Australia: loose leaves for letters, lithographic paper, sketching paper, watercolour paper, notebook paper, and packing paper to protect their bird specimens from weeping blood onto their feathers.

In a letter to her mother, Elizabeth writes that John, in his enthusiasm ‘has already shown himself a great enemy to the feathered tribe, having shot a great many beautiful birds and robbed various others of their nests and eggs’ (Chisholm: 33). She does not, however, betray her own position. Rather, in her correspondence and diary Elizabeth Gould presents as a good Christian woman, a pious Victorian mother concerned with the welfare of her family and friends in England. She laments the small irritations of colonial life, the poor quality goods, for instance, the difficulties householders experienced with the convict ‘help’, before reiterating her longing to return home. Only occasionally does she allow a kind of tremulous excitement–in her responses to Sydney and Hobart’s natural landmarks and to the climate and flora–creep in. Elizabeth’s personal views about her artwork, apart from depicting herself as diligent and hard-working, are never elaborated. Her struggles and sufferings, her satisfaction at a technical or aesthetic breakthrough, are not shared with her home-readers.

While John Gould’s biographers have granted him traits of passion, eccentricity, genius and even ruthlessness, no critic has spoken in other than reserved and respectful (sometimes patronising) tones about Elizabeth’s temperament and personality[1]. As a biographical subject, she is presented as frustratingly one-dimensional: obedient, dedicated, and burdened by an excess of motherly concern [2].

Your letter of February has reached us and was read with mixed feelings of pain and pleasure–pain for the state of health in which poor Louisa has so long continued and pleasure that you, my dear Mother, are so very well and have escaped your usual attack during the winter. (Chisholm: 66)

I hope my dear Mother, we may meet again next year in health. (Chisholm: 66)

Although Alec Chisholm is fond of quoting Elizabeth’s yearning to reunite with her children, he does not mention the fact that the person she frequently worried about never seeing again, was her own mother. Elizabeth Coxen’s mothering experiences can only be described as tragic; she buried three infant daughters, each christened Mary, and outlived all except one of her eleven children, including Elizabeth Gould. In old age Elizabeth Coxen suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and other vague bodily ‘complaints’, especially those brought on during winter. Ironically, during John’s and Elizabeth’s time in Australia, Mrs Coxen enjoyed robust health. But this was not the case with Elizabeth’s youngest daughter, Louisa Gould, six months of age when her parents departed England. Louisa suffered from an unnamed debilitating illness–a wasting disease, in Victorian medical terms–for a period of three months.

The following is a quotation from Edwin Prince, granted power of attorney over the Goulds’ business affairs during their absence:

I know you will be anxious to know how we all are after the winter: and on this point I am sorry to say my report must be far from favourable. […] Both your little ones have also been indisposed particularly Miss Louisa who in fact continues so delicate that I have deemed it my duty to speak to Mr Russell about her being sent into the Country which will be done as soon as he considers the season sufficiently advanced to produce a favourable result. You must not imagine there is any cause for alarm now though at one time Mr Cox assures me that both Mr Russell and himself did not think it possible she could survive. (Sauer: 46)

Prince signed off with a postscript, begging Gould not to ‘allude’ in his letters home to ‘what I have said about Mr Russell’ (Sauer: 47). From the tone of Elizabeth’s correspondence, it seems that although she was informed of her youngest daughter’s sickness, she wasn’t told of its serious extent, and nor the concerns of Louisa’s doctor. How might she have responded? How does somebody like me, living in the twenty-first century, hope to imagine the sorts of pressures and fears Victorian women faced? When Elizabeth left England for Australia, she had already buried two infant sons. She knew she would be separated from her three youngest children for at least two years, and worried continually that she might be detained for longer. It’s a challenging task to re-create the interiority of an 1830s adventurer and artist–expeditions such as the Goulds’ undertook were fraught with danger–willing to risk the very real possibility that she would never see her family again.

The construction of a relative self in the memoir is no less difficult [than the absolutist view of traditional autobiography]: the person writing now is inseparable from the person the writer is remembering then. The goal is to disclose what the author is discovering about these persons: But such a goal can arise only in the writing of the memoir, a discovery which then becomes the story. (Larson: 20)

Along with researching the Gouldian archive, to write my historical novel I had to learn the art of composing memoir. Thomas Larson’s The Memoir and the Memoirist encouraged self-reflective writing, which I began to practise, keeping a journal about my research experiences, a kind of exercise to loosen me up before exploring the narrative of Elizabeth Gould. I regarded my week-long trip to Sydney as an opportunity to engage in self-reflective writing outside of my usual work routine, hopefully providing a portal back into my stalled creative dissertation. Although no comparison can be drawn between my separation from my son and daughter for a week, and Elizabeth Gould’s two year long period of living apart from her three youngest children, it was all I had in terms of a window through which to view my thought-processes and perceptions away from normal family life. I determined to use some of my time creatively, as a writing exercise, a springboard to launch me back into the acrobatics of transforming the historical subject of Elizabeth Gould into a compelling fictional character.

Choice of subject often originates in early ideals or identifications and … it may be important for [the biographer] to accept as well as he can some deeper bias than can be argued out on the level of verifiable fact or faultless methodology. (Eakin: 197)

It was only in being able to take the trip to research Elizabeth Gould’s artworks that I began to detect new fracture lines of understanding about my own experiences as a parent and creative practitioner. The last time I was in Sydney, two years ago for the Sydney Writers’ Festival, marked a turning point in my identity as a mother. I was ready to emerge from the immersive fold of raising infants and toddlers and pick up the threads linking me to my former, intellectually-defined, self. Since that festival, I’ve been less confused, less guilty and less harried, as if something fundamental had shifted, as if I’ve finally gained a stable emotional perspective. Because prior to that stimulating conference of ideas I felt swamped–engulfed–as they say in psychiatry, by the responsibilities and steep learning curve of simply becoming a mother.

In some ways I chose to write about Elizabeth Gould for obvious reasons. The simple narrative is that my partner rescued a bird from a tennis court net. He asked me to buy a cage and find a book about caring for parrots. I borrowed the book from a bird-enthusiast friend, who loaned me Isabella Tree’s 1991 biography of John Gould, John Gould: The Bird Man. In Tree’s extraordinary narrative, I discovered the little-known role Elizabeth played in illustrating her husband’s early books. I found Elizabeth’s ability to manage a large family and demanding creative career intriguing and compelling, her early death inserting a note of tragedy into the story arc.

On day three of my trip I was given permission to view and photograph the short diary Elizabeth Gould wrote while travelling in the Hunter Valley in 1839. I picked up the cardboard box from the special collections desk. It was tied with thick ribbon, inside which notes had been tucked. I untied the ribbon and lifted the lid off the box to find a large object wrapped in acid-free tissue paper. It also had a ribbon attached. A note in the corner of the record read ‘do not issue.’ I undid the string and unfolded the layers of paper, revealing a leather-bound ‘letterbook’ belonging to John Gould. In the middle of the book, amongst copies of the ornithologist’s correspondence made by his secretary, Edwin Prince, was tucked a small booklet, about the size of a CD case. This was the travel diary Elizabeth kept while journeying by coach, ferry and steamer from Sydney to Maitland. The words, scrawled in ink and later pencil, were few, totalling some six double-sided leaves. The pages had been salvaged, hidden like a pressed flower inside her husband’s abandoned letterbook, and in this manner preserved for me to read almost two centuries later. The effort it had taken me to be granted permission to view the record, along with the process of physically unwrapping the layers of protective covering, the diary itself tucked inside an artefact filed under John Gould’s name, struck me as a metaphor for my search for Elizabeth Gould, the historical subject and the fictional creation.

Writing the first draft of Elizabeth Gould: A Natural History, I was overwhelmed by the circumstances of my point-of-view narrator’s wilful separation from her children. I felt both drawn to this historical character and befuddled by her enigmatic life choices. As a consequence, I over-wrote her sense of frustration, anxiety and guilt at the regretful abandonment of her children in order to travel to Australia. My empathic identification with my subject created a barrier to imagining Elizabeth Gould’s aesthetic and scientific discoveries while in Australia. It may seem obvious, but the insight I had during my research trip, that one’s relationship with one’s children passes through periods and stages, allowed me to relax into a deeper and more nuanced exploration of my character’s experiences as an artist, traveller and adventurer.

It was in viewing Elizabeth Gould’s colouring precision–how carefully she built up tone, her attention to a body part as tiny as a pardalote’s ankle, a kingfisher’s eye-ring–that I began to really gather gems for characterising her as a point of view narrator. It was in photographing detail of mandible bristles and feather barbs that I came to appreciate her personal investment in continually honing and developing her ability to depict Australian species with scientific accuracy and aesthetic grace. If a few of Elizabeth’s earliest efforts at lithography, like any beginner, were a little stiff and flat (McEvey 1973: 16), ten years later, in December1840, when the first plates for The Birds of Australia were released, she had made extraordinary progress as a zoological artist. This, to me, speaks directly, where Elizabeth’s correspondence and diary failed, of her passion, commitment and determination to succeed aesthetically. Collaborating with John Gould by accompanying him to Australia to draw the continent’s animals and plants was so much more than a curious pastime for Elizabeth Gould. She was as dedicated as her more talked-about husband to their artistic and scientific collaboration, evident in the extraordinary hand-coloured lithographs she designed to showcase the early nineteenth century’s most compelling Australian birdlife.

Notes

[1] See McEvey, Chisholm and Jackson

[2] See Chisholm and McEvey

Works cited

2011 (July) ‘Collector Chat: The Official Monthly Newsletter for Antiques and Collectables for Pleasure & Profit’, Speedie Graphics

Bowdler Sharpe, R 1893 An Analytical index to the works of the late John Gould, Sotheran, London

Chisholm, A.H. 1944 The Story of Elizabeth Gould, Hawthorne Press, Melbourne

Datta, Ann 1997 John Gould in Australia: letters and drawings: with a catalogue of manuscripts, correspondence, and drawings relating to the birds and mammals of Australia held in the Natural History Museum, London, Miegunyah Press, Carlton

Eakin, Paul John 1992 ‘Writing Biography: A Perspective from Autobiography’, in Ian Donaldson, Peter Read and James Walter (eds) Shaping Lives: Reflections on Biography, Australian National U, Canberra

Farber, Paul 1982 Discovering Birds: The Emergence of Ornithology as a Scientific Discipline, 1760-1850, Johns Hopkins UP, Baltimore

Jackson, Christine L 1975 Bird Illustrators: Some Artists in Early Lithography, H. F. & G. Witherby, London

Larson, Thomas 2007 The Memoir and the Memoirist: Reading and Writing Personal Narrative, Swallow P/Ohio UP

McEvey, Allan 1973 John Gould’s Contribution to British Art: A Note on Its Authenticity, Sydney University Press for the Australian Academy of the Humanities, Art Monograph 2, Sydney

McEvey, Allan 1967-68 ‘John Gould’s Ability in Drawing Birds’, in Ursula Hoff (ed) Art Bulletin of Victoria, The National Gallery of Victoria

Russell, Roselyn 2009 ‘Elizabeth Gould: The Mother of Australian Bird Study’, National Library of Australia, Canberra: http://www.nla.gov.au/pub/nlanews/2009/jun09/elizabeth-gould-mother-of-australian-bird-study.pdf

Russell, Roselyn 2011 The Business of Nature: John Gould and Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra

Sauer, Gordon 1998 John Gould the Bird Man: Correspondence Volume 2, 1839-1941,

Maruizo Martino, Mansfield Centre, CT

Tree, Isabella The Bird Man: The Extraordinary Story of John Gould, Ebury P, London

First published in Text Journal

when I was 19, sitting with 300 psych students making notes on week three’s ‘human sexuality’ lecture. Next to me slouched my best friend and flatmate, with whom I’d taken the previous semester’s ‘philosophy and sex’. We were both, back in then, in our different ways, utterly obsessed with sex. He spent a lot of time in his room, ‘studying’; I went out on the weekends and met boys. For whole evenings we dissected our crushes and pickups on the broken couch in the lounge, while in the kitchen enormous cockroaches scuttled over the water-damaged mustard cupboards for noodle crumbs. I lent him Anais Nin and he photocopied me anthropology papers about polyandry and wife-sharing. For human beings, monogamy was doomed to failure and with our hormone-soaked minds, we whole-heartedly agreed. Not that either of us knew the first thing about it.

when I was 19, sitting with 300 psych students making notes on week three’s ‘human sexuality’ lecture. Next to me slouched my best friend and flatmate, with whom I’d taken the previous semester’s ‘philosophy and sex’. We were both, back in then, in our different ways, utterly obsessed with sex. He spent a lot of time in his room, ‘studying’; I went out on the weekends and met boys. For whole evenings we dissected our crushes and pickups on the broken couch in the lounge, while in the kitchen enormous cockroaches scuttled over the water-damaged mustard cupboards for noodle crumbs. I lent him Anais Nin and he photocopied me anthropology papers about polyandry and wife-sharing. For human beings, monogamy was doomed to failure and with our hormone-soaked minds, we whole-heartedly agreed. Not that either of us knew the first thing about it.

pital. My name’s called in the waiting room and I’m led through double doors, shown into a small office. A vivacious nurse questions me about fasting, allergies, former operations. I’m weighed, ‘so they give you the right amount of anaesthetic,’ and handed blue-green scrubs for my hair and feet. I remove all clothing except my underpants and am tied into a gown. The nurse clips a nametag around my wrist, joking about not getting me muddled up with somebody else.

pital. My name’s called in the waiting room and I’m led through double doors, shown into a small office. A vivacious nurse questions me about fasting, allergies, former operations. I’m weighed, ‘so they give you the right amount of anaesthetic,’ and handed blue-green scrubs for my hair and feet. I remove all clothing except my underpants and am tied into a gown. The nurse clips a nametag around my wrist, joking about not getting me muddled up with somebody else.

Finished grooming the outer skin, I insert a measured length of dowel up through the neck and into the cervical cavity at the base of the skull, around which I wind cotton wool and then Dacron, or mattress-stuffing, which puffs out under the skin, plumping like tissue and giving a lifelike appearance. I then thread a needle and begin to stitch the incision running from clavicle to cloaca–the dual purpose opening through which the bird passes reproductive material and waste. I cross its feet at the ankles and use string to tie them around the dowel rod. A label is attached to the string, identifying the bird by scientific name, location, date, and specimen number, all corresponding to details recorded in the zoological register. Fine surgical gauze is then mummy-wrapped around the bird, beginning at the shoulders and moving down to the tail, to enable it to ‘set’ and dry, a process which takes about three weeks. After this, the specimen will keep its shape and can be stored flat in a collection drawer.

Finished grooming the outer skin, I insert a measured length of dowel up through the neck and into the cervical cavity at the base of the skull, around which I wind cotton wool and then Dacron, or mattress-stuffing, which puffs out under the skin, plumping like tissue and giving a lifelike appearance. I then thread a needle and begin to stitch the incision running from clavicle to cloaca–the dual purpose opening through which the bird passes reproductive material and waste. I cross its feet at the ankles and use string to tie them around the dowel rod. A label is attached to the string, identifying the bird by scientific name, location, date, and specimen number, all corresponding to details recorded in the zoological register. Fine surgical gauze is then mummy-wrapped around the bird, beginning at the shoulders and moving down to the tail, to enable it to ‘set’ and dry, a process which takes about three weeks. After this, the specimen will keep its shape and can be stored flat in a collection drawer.

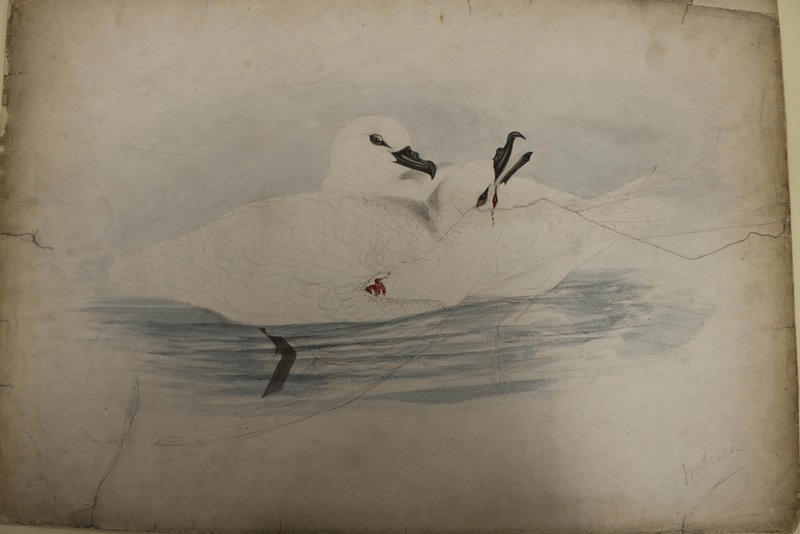

Gould Drawing Number: 2285

Gould Drawing Number: 2285 Cape Petrel

Cape Petrel

Figure 2. Study of flying fish, said to move like locusts, by Elizabeth Gould

Figure 2. Study of flying fish, said to move like locusts, by Elizabeth Gould Figure 3 Cape Petrel with blood from feeding Watercolour and pencil study by Elizabeth Gould

Figure 3 Cape Petrel with blood from feeding Watercolour and pencil study by Elizabeth Gould Figure 4. Spectacled Petrel study by Elizabeth Gould 1837

Figure 4. Spectacled Petrel study by Elizabeth Gould 1837

Figure 8. Wilson’s Storm Petrel study skins courtesy of the Queensland Museum

Figure 8. Wilson’s Storm Petrel study skins courtesy of the Queensland Museum