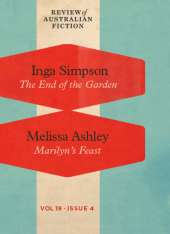

It’s lovely to have a new piece of fiction published. It’s been a long time. Check out the latest issue of Review of Australian Fiction, Volume 19, Issue 4, for my short story: “Marilyn’s Feast.”

It’s lovely to have a new piece of fiction published. It’s been a long time. Check out the latest issue of Review of Australian Fiction, Volume 19, Issue 4, for my short story: “Marilyn’s Feast.”

Thanks to Inga Simpson for partnering with me.

Marilyn’s Feast (preview)

Marilyn’s Feast (preview)

Marilyn scanned the labels for additives and chemicals but the ingredients lists were equally full of rubbish. How about a visual test? No such luck: the two vacuum-packed slices of prosciutto seemed identical. There was always the supermarket’s deli, though the thought of all that raw pink chicken and soft white fish jumbled amongst the cold cuts had her picturing salmonella cultures, listeria. She supposed she could drive to The Stuffed Truffle, get some freshly sliced. Was that going overboard?

A yellow tag beneath Coles’ gourmet range caught her attention. They were on special—still expensive. Bugger it. She grabbed three packages and crossed prosciutto off her list. In the meat aisle she chose the bulk pack of rump steak. Her recipe called for gravy beef, but the last time she used gravy beef she’d spent ages chopping out the gristly bits, dumping them in a plastic bag which she shoved into the bowels of the freezer. An attempt at environmental awareness had her boil it down for stock—waste not want not—but a foamy-scunge floated to the top of the saucepan and it smelt repulsive and she’d ended up flushing it down the toilet.

The bill amounted to a small fortune, the clerk passing her the long, carefully folded docket, which she screwed into a ball and threw under the cigarette counter.

John need never know.

She ordered lilies from the florists and at the liquor barn a mixed dozen of red, white and bubbly, plus a carton of discounted Mexican beer. In the car park she had trouble closing the boot and had to rearrange several of the environmental bags.

Her phone buzzed and she jerked to a stop at an orange traffic light, the driver in the car behind beeping his horn. She flipped open the casing but it was too late; the call had gone to voice mail. In the darkness of the garage she retrieved the text: Buster head cold. Have 2 cancel L. Nerves soured her stomach. What was she to do with all the alcohol? The extra food? She was ridiculous, out of control. The engine ticked like a timer about to go off but she stayed clipped into her seat, wondering if John would take the initiative and come out and help her unload.

Outside the study she smoothed her cords and shirt, jiggled the doorknob.

John was on Facebook. ‘There’s beers in the car,’ she began. ‘Not to mention a shit-load of heavy groceries.’

A tiny muscle in his cheek popped.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I didn’t mean to be rude. I’m just stressed about tonight.’

John stretched, his blue t-shirt revealing his navel hair. He shut the laptop.

‘You know I hate having to ask.’ She tasted sweat above her lips.

He came at the doorway side-on, all hip and shoulder and defence; she flattened herself against the frame, stomach pulled in tight, to let him through.

She shambled after him, a flightless bird, aware of her thighs rubbing, the elastic of her underpants slicing into her hips, feeling like her flesh had no borders. ‘I’ll get lunch ready, okay? Would you like a cup of tea?’

She was yet to print the online olive tapenade recipe. She dashed back to the computer, patting the mouse and making the screen flick to life. John had forgotten to log himself out of Facebook. Curious, but unaware of making any decision, she found herself – hand on mouse, eyes on screen – scrolling John’s friends. His writer buddies posted an awful lot—links to publishing news items, word counts, up and coming events, milestones. Below a video, loaded by a television producer mate, was a series of comments by a ‘friend’ called Meggie. Marilyn tried to put a face to the name but couldn’t remember John ever talking about her. Something in the postings’ gushy tone made her uneasy.

She listened down the hallway—John was still bringing in groceries—and with her left foot shut the door. Clicking onto the tab for ‘Messages,’ she worked her way down the screen until she came to Meggie’s thumbnail. Most of the thread’s commentary was inane. The girl was a student of some kind. She paged back to the original email:

Hi John, it was great to see you the other day. Thanks for making the effort to come over, I appreciated it. Thanks, also, for talking shop. It’s good to get some expert opinion. And support.

A few entries later, she discovered another post. For five minutes she read and calculated and tallied, piecing together scraps of detail until she had the meeting narrowed down to a particular afternoon last May. It was the first day of John’s week off and he’d mentioned several times that he wanted to go shopping for his friend Clayton’s fortieth birthday. It was so out of character she’d wondered if he wasn’t organising a surprise for her. But when he got back and she asked what he’d bought, the expression on his face was vague. He said he hadn’t found anything yet, that he’d have to have another look. She’d given the incident no further thought.

I’m a slow writer. Fast, when I have the idea sorted out, be it the outline, the chapter, the character sketch, but in the lead up to these flurried bursts of keyboard tapping, there are months, weeks, years – Toni Morrison calls it ‘playing in the dark’ – of uncertainty and unease. The requirement of much patience, of inventive healthy (and no-so much), antidotes to that humming motor of anxiety. What surprises me, over and over, are the number of possibilities for the next big project that need to be sifted through before I can settle upon the one that has all of the required parts.

I’m a slow writer. Fast, when I have the idea sorted out, be it the outline, the chapter, the character sketch, but in the lead up to these flurried bursts of keyboard tapping, there are months, weeks, years – Toni Morrison calls it ‘playing in the dark’ – of uncertainty and unease. The requirement of much patience, of inventive healthy (and no-so much), antidotes to that humming motor of anxiety. What surprises me, over and over, are the number of possibilities for the next big project that need to be sifted through before I can settle upon the one that has all of the required parts.![160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca[1][1]](https://melissaashleycomau.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca11.jpg?w=274&h=361) I do think the memoir project is a keeper, though not for now. The on-the-road jag is dead to me. But the novel of the Sun King and the Old Regime, keeps flashing in the peripherals of my daily life; as I fall asleep, as I drive, drinking a glass or wine (or two), reading my students’ drafts, such that I’m going to give it a chance. I’m saying yes to its long courtship. For it has everything and more to keep me occupied, entertained. After a long wait, I’m thrilled to be back to my desk, the agony (I do not exaggerate) of midwifing my first novel forgotten, eager to fill in some new blanks.

I do think the memoir project is a keeper, though not for now. The on-the-road jag is dead to me. But the novel of the Sun King and the Old Regime, keeps flashing in the peripherals of my daily life; as I fall asleep, as I drive, drinking a glass or wine (or two), reading my students’ drafts, such that I’m going to give it a chance. I’m saying yes to its long courtship. For it has everything and more to keep me occupied, entertained. After a long wait, I’m thrilled to be back to my desk, the agony (I do not exaggerate) of midwifing my first novel forgotten, eager to fill in some new blanks.

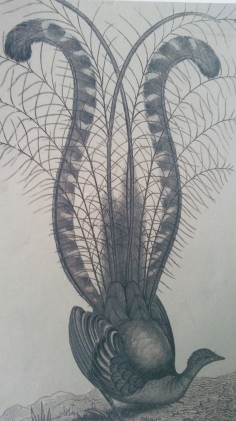

Elizabeth Gould was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover and helpmate to a passionate and demanding genius, and as a devoted mother who gave birth to eight children. In a society obsessed with natural history and the discovery of new species, Elizabeth Gould was at its glittering epicentre. Her artistry breathed life into hundreds of exotic finds, from her husband’s celebrated discoveries to Charles Darwin’s famous Galapagos Finches.

Elizabeth Gould was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover and helpmate to a passionate and demanding genius, and as a devoted mother who gave birth to eight children. In a society obsessed with natural history and the discovery of new species, Elizabeth Gould was at its glittering epicentre. Her artistry breathed life into hundreds of exotic finds, from her husband’s celebrated discoveries to Charles Darwin’s famous Galapagos Finches. Fired by Darwin’s discoveries, in 1838 Eliza defied convention and her own grave misgivings about leaving all but one of her children behind in London in the care of her mother by joining John on a trailblazing expedition to the untamed wilderness of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales to collect and illustrate Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.

Fired by Darwin’s discoveries, in 1838 Eliza defied convention and her own grave misgivings about leaving all but one of her children behind in London in the care of her mother by joining John on a trailblazing expedition to the untamed wilderness of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales to collect and illustrate Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.