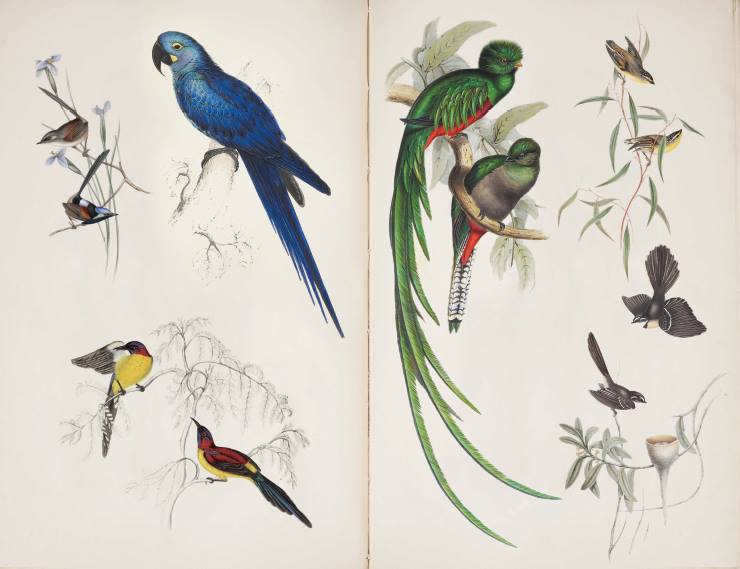

“Beak gamboge yellow; head covered with long filamentous plumes forming a rounded crest; from the shoulders spring a number of lance-shaped feathers, which hang gracefully over the wings; from the rump are thrown off several pairs of narrow flowing plumes, the longest of which, in fine adults, measure from three feet to three feet four inches; the others gradually diminishing in length towards the rump, where they again assume the form of the feathers of the back ; these plumes, together with the whole of the upper surface, throat and chest, are of a most resplendent golden green; the breast, belly and vent are of a rich crimson scarlet ; the middle feathers of the tail black ; the six outer ones white for nearly the whole length, their bases being black, feet brown.”

This is John Gould’s description of the resplendent quetzal, taken from the letterpress accompanying his illustration of the species in his Monograph of the Trogons, (1858-1875. second edition). The resplendent quetzal, Pharomachrus mocinno, is a Central American trogon that resides in the region’s remote cloud forests. One of the world’s most stunning birds, it features prominently in Mayan mythology and not only is it Guatemala’s national bird, the country’s local currency also bears its name. The resplendent quetzal’s long tail feathers were a Mayan status symbol, worn only by chiefs and high ranked warriors. Killing or harming a quetzal was said to bring bad luck and for this reason, after special hunters removed its tail feathers, the bird was released back into the wild. Legend has it that the male resplendent quetzal’s breast feathers turned scarlet keeping vigil at the side of a Mayan chief as he bled to death from the attack of a Conquistador.

On Thursday I had the pleasure of paying a visit to the Queensland Museum to photograph the resplendent quetzal with my sister, Vikki Lambert, for some of the artwork for The Birdman’s Wife. In 1836 Elizabeth and John Gould created a hand-coloured lithograph of the male and female resplendent quetzal, one of their most stunning plates. The print was highly unusual in that the Goulds joined two folio sheets together in order to fully render the male’s magnificent tail plumage; in a mature adult the tail plumes are three times the length of its body. Elizabeth’s hand-coloured lithograph does full justice to the quetzal’s bizarre, unforgettable form, which of course, is only fitting.

In writing The Birdman’s Wife, I tried to portray the exhilaration Elizabeth Gould must have felt after the plate’s completion. How impatient, how excited she must have been to share her masterpiece with the bird aficionados who subscribed to the folios she produced with her husband. The lithograph was a landmark achievement, unsurpassed in its day – the aesthetic and scientific potential of lithography only really came into its own in 1830, with the publication of Edward Lear’s (of limerick fame) monograph of the parrot family. Elizabeth used a technique of applying powdered metallic dust to the completed watercolour, to capture the iridescence of the quetzal’s plumage when held under light.

Very generously, The Queensland Museum library granted me permission to photograph an original plate, from the Goulds’ Monograph of the Trogonidae, or Family of Trogons (1835-1838). The monograph, superseded by a second edition in 1858, is extremely rare, with only two copies held in Australian libraries. The resplendent quetzal, notoriously difficult to encounter in its natural habitat, proved a challenge to photograph, requiring many adjustments of position and lighting to adequately render its brilliance. With the patience and assistance of librarian Meg Lloyd, and the the perseverance of my photographer, Vikki, after several hours, we finally succeeded.

The curator of the museum’s zoology collections, Heather Janetski, retrieved a precious study skin of the resplendent quetzal from the museum’s holdings for us to photograph as well. The specimen was collected in the 1870s, its faded field tag penned in a careful, flowing script. To prevent insect infestation, 19th century ‘stuffers’ used a lethal combination of arsenic and lead; thus in handling the skin, I had to wear gloves. I had the oddest sensation cradling the resplendent quetzal specimen, keeping still for the perfect shot; it felt as if I where nursing a days-old infant. Which relates in a lovely way to John Gould’s observation in the text accompanying Elizabeth Gould’s wonderful plate – male and female quetzals are said to mewl across their forest canopies during mating season, making a sound like a newborn child.

My dream for more than a decade, was to have a novel published. I am very fortunate to have signed with Affirm Press, who have worked tirelessly — many, many thanks to Christa Moffett, Karen Cook, Kathryn Lafferty and Fiona Henderson — for all the work you have put into finding, funding and designing these exquisite endpages featuring the artworks of Elizabeth Gould. (The indigo macaw is Edward Lear’s.) I could not be more pleased and excited!

My dream for more than a decade, was to have a novel published. I am very fortunate to have signed with Affirm Press, who have worked tirelessly — many, many thanks to Christa Moffett, Karen Cook, Kathryn Lafferty and Fiona Henderson — for all the work you have put into finding, funding and designing these exquisite endpages featuring the artworks of Elizabeth Gould. (The indigo macaw is Edward Lear’s.) I could not be more pleased and excited!