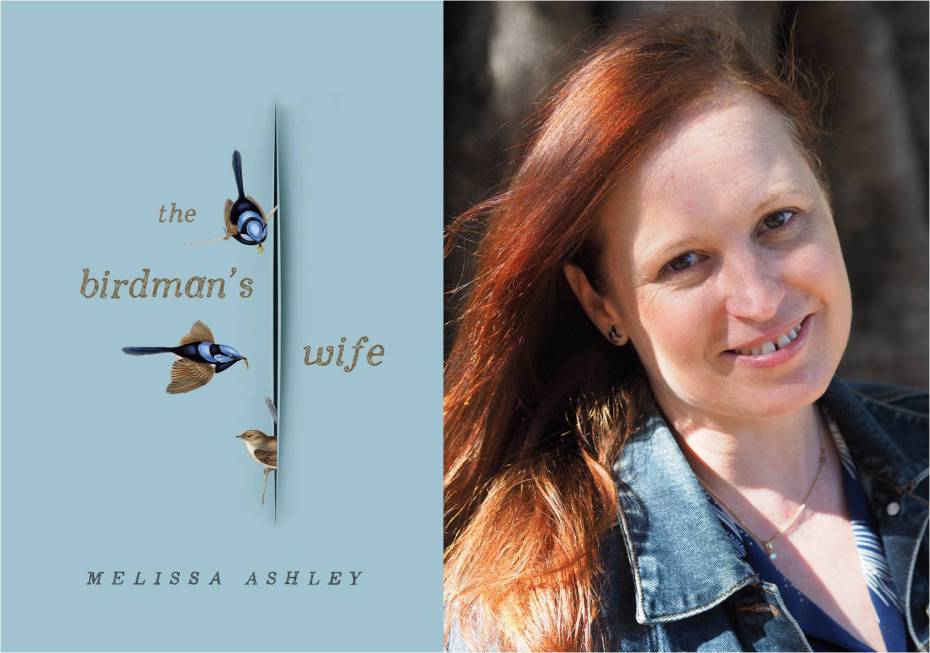

Author: Melissa Ashley

Good Reading Magazine interviews Melissa Ashley: Meet the woman responsible for John Gould’s Fame

Good Reading Magazine

Elizabeth Gould’s artistry and technical skill as an illustrator breathed life into hundreds of newly discovered species, and was crucial modern ornithology and classification. She illustrated the species of finches that gave rise to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and produced hundreds of the lithographs of birds that made her husband, John, famous. In The Birdman’s Wife, Melissa Ashley has imagined the life of Elizabeth as a mother, birdwatcher and artist, giving well-deserved recognition to this incredible historical figure. Melissa tells gr about her passion for Australian birdlife, her dealings with taxidermy, and how falling in love with a poet lead her to write this book.

Why do you think Elizabeth Gould’s story and skill as an illustrator have been largely uncelebrated, and what made you decide to dedicate an entire book to rectifying this lack of recognition?

John Gould, the famous 19th ornithologist, created one of the most enduring brands in natural history as ‘The Birdman’ and the ‘father’ of Australian ornithology and is renowned for creating the most sublime images of birds the world had ever seen before. But few people know that his wife, Elizabeth Gould, was the artist who illustrated and designed more than 600 of the exquisite hand-coloured images he is famous for. Yet her legacy has been overshadowed by his fame. Almost two hundred years of analysis of John Gould and his contributions to ornithology and zoological illustration have created a colossal figure. Conversely, time and time again, Elizabeth has been consigned to his shadow. Elizabeth was viewed as either John Gould’s faithful and supportive wife, or his willing assistant and acolyte. Onto these interpretations were projected all kinds of stereotypical feminine qualities, that she was delicate, polite, elegant and deferent. Some critics even go so far as to suggest that she sacrificed her very life for her husband’s pursuits.

But the real Elizabeth was a woman of substance and a woman ahead of her time, juggling her work as an artist with her role as wife and mother to an ever-growing brood of children. Yet her creative output was extraordinary. She was a passionate and adventurous spirit, defying convention by embarking on a two-year expedition to the Australian colonies with her husband to collect and illustrate our unique birds and plants. At a time when the world was obsessed with discovering natural wonders, Elizabeth was as at its epicentre, working alongside legends like Edward Lear and Charles Darwin. Yet in many of the books about John Gould it would be impossible to find this woman. At last in The Birdman’s Wife I have been able to tell her amazing story and overturn some of the outdated misconceptions about her.

What motivated you to imagine and evoke Elizabeth’s life with fiction rather than as a biography?

It all started when I fell in love with a poet, and with his poem about a bird. We became avid birdwatchers together. Writers, too. When he rescued a ringneck parrot and we adopted it as a pet, a friend gave me a book about caring for parrots and a biography about John Gould. That was how I discovered that his wife, Elizabeth, created the beautiful images of birds he wrote about in his exquisitely illustrated folios. She was portrayed as such a shadowy figure yet her work as an artist was so key to his fame and the history of birds that I became enthralled with her. I began researching Elizabeth’s life in earnest and the more I learned about her, the more determined I became to uncover her story.

I’ve always loved stories about women who are overlooked by history, and I find creative artistic relationships fascinating – Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley; Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning – so Elizabeth and John Gould’s intimate creative relationship added an extra spark of interest. Elizabeth Gould was such an intriguing enigma that I became convinced that she would be the ideal protagonist for an historical novel and so I made her the subject of my PhD in creative writing. Writing a novel rather than biography allowed me to fill in the gaps of her narrative, to imagine and bring to life what it might have felt like to be a mother to six children, a busy career woman and an adventuress in the early 19th century. It’s not possible to achieve the level of lyricism and emotional depth I wanted to bring to the story in a biography. For me, it was never a question of writing biography. From the get-go I wanted to write a fictional reimagining and revitalisation of her incredible experiences and personality.

How did you go about imagining her voice and personality to the extent that you were able to focalise through her? What was she like?

I’m a researcher by training and I love nothing more than digging into files and archives. For Elizabeth’s story that meant 1830s London and Australia; ornithology, zoological illustration, voyages of exploration, childbearing practices. I came to a stage where I felt I had spent enough time with printed books. I needed to follow in the footsteps of my heroine and get out into the field, go birdwatching, learn bird-stuffing and, ideally, to handle archival materials that Elizabeth Gould made herself, which I was finally able to do in the State Library of NSW. The discovery of her letter book in John Gould’s papers helped me to make the jump from the biographical Elizabeth to imagining her emotional journey, her personal experiences and challenges, and finding her voice as the narrator of The Birdman’s Wife.

Elizabeth was a naïve young woman when she fell in love with a passionate and ambitious genius but she came into her own as a woman, an artist and a mother. She was fierce and loyal, a loving mother and a loving partner. She was a talented artist, with an artist’s flair not only for the visual but what lies beneath. She loved poetry and literature and the symbolism of birds rather than just the science behind them. Her letters showed she was was clever and witty, and her strength of character is clear in her ability to get on with life for the sake of her family after losing two of her children. Elizabeth’s experiences as a working mother will certainly resonate with many modern readers but her achievements, her warmth and humour, her loving nature and her willingness to take risks, so unusual for a woman of her time, make her an irresistible and exciting character for a novel.

What forms of research were the most useful in yielding details about Elizabeth? Did you discover anything that surprised you?

I researched by reading biographies, histories of the discovery of Australian birds, and also went on field trips to the Upper Hunter Valley and Hobart, where Elizabeth spent most of her two year expedition in Australia. Thanks to a travel grant from the University of Queensland, I was able to visit a little town in Kansas called Lawrence, where the largest Gouldian archive in the world is held. There I found countless resources, manuscripts, original versions of Elizabeth and John’s beautiful folios, and a swathe of correspondence from researchers into the Goulds’ lives. I discovered that the Goulds’ son, Charles, a character in The Birdman’s Wife, wrote a book called Mythical Monsters, where he tried to argue that creatures like the hydra and the gorgon had really existed and were now extinct. I also found documents related to the deaths of Elizabeth’s sons, John Henry Gould and Franklin Gould – characters in the novel as well – who both died of dysentery while at sea. They perished in separate incidents and the detailed reports from the chaplains and surgeons aboard their ships regarding the medicines and religious rites they received helped me to write about Elizabeth’s experience of childbed fever.

What do you think drew the Goulds – and yourself – to the investigation and illustration of birdlife?

My passion for birds and how they fascinate and inspire us. I am an avid birdwatcher and I am fascinated by antique etchings and prints of birds; I love the illustrations’ awkward grace. In 2004, the discovery of a cache of 56 paintings of Australian birds and plants by George Raper, a midshipman and navigator on the First Fleet, seized my imagination. The watercolour paintings were uncovered in England during an inventory of the estate of Lord Moreton, the Earl of Ducie. Intrigued by the illustration of a laughing kookaburra, one of the evaluators brought the buried collection to light. Once part of Sir Joseph Banks’ First Fleet materials, the collection had passed into the Ducie family and lain untouched for two hundred years. This was a truly astounding find. Although Raper’s paintings were naïve, his attention to the details and colours of the birds’ wings and feathers was extraordinary. By this time my birdwatching had intensified into a near obsession, and I began to travel great distances to encounter new species, which I would excitedly add to my ‘life list’, a record of birds seen for the very first time. The excitement of this pursuit led to me wonder what it might have felt like for George Raper and his fellow First Fleet bird enthusiasts’ when they encountered Australia’s unique birds, so utterly different to the species of Britain and Europe, for the first time.

The appeal of delving into Elizabeth Gould’s forgotten history, of trying to imagine how it must have felt for them to see, paint and collect species that had never been encountered before, connected to my own thrill when twitching a new species of bird for the first time. Elizabeth began illustrating birds for John well before they embarked on their publishing venture. So John was already aware of her great skill. The crucial experience for John and Elizabeth was meeting 18-year-old Edward Lear. The young artist was going to publish a monograph on parrots, vowing to illustrate every caged parrot in England. Upon viewing his magnificent lithographs of macaws and black cockatoos, Gould – already making a good living as a taxidermist and museum curator – became inspired to undertake his own publishing and illustrating venture, employing Elizabeth as his artist. Elizabeth was a crucial part of John’s enterprise from the very beginning. Indeed, I think it is safe to say that if Elizabeth wasn’t willing or such a skilled artist, Gould would never have attempted the project.

Are many of the species brought to life by Elizabeth’s artistry now extinct?

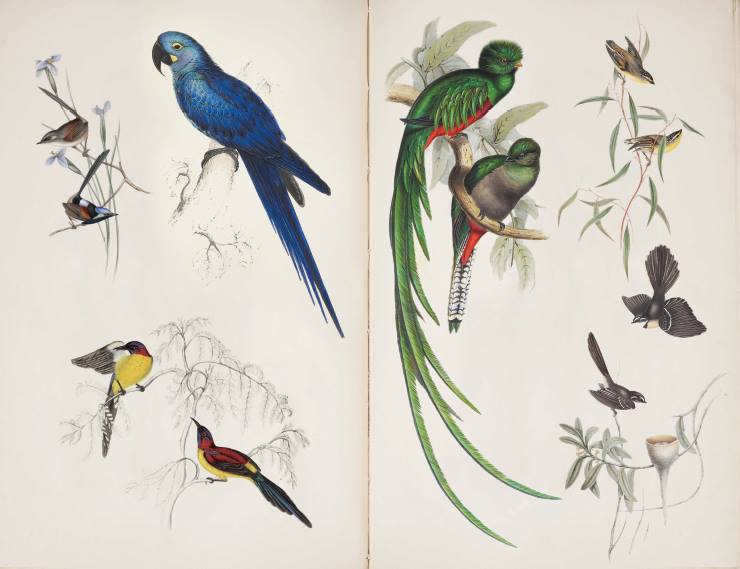

There are two that I can think of; the Norfolk Island Kaka, a ground parrot like the Kea from New Zealand. Never particularly abundant on the island – it had been hunted for food by Polynesians who travelled to Norfolk Island to gather food – as well as the starving penal colony that arrived on the island in 1788 and further decimated the scant population. The last kaka to perish was a caged pet, expiring in London in 1851. Elizabeth’s lithograph of the species is very special, both in an artistic and a scientific sense. Not only is the illustration utterly beautiful – it’s featured in the endpapers of The Birdman’s Wife – but it’s one of the last records of this extinct species.

The other is the Huia, a New Zealand endemic. This black, yellow-beaked bird was hunted to extinction thanks to a 19th century passion for its feathers, worn by women – like ostrich plumage – in their fashionable hats. King George was seen with a Huia feather in his hat, which ignited demand for the sleek black feathers. Although John Gould killed species for science, he only took what was needed. He strongly disapproved of using bird feathers for fashion. On his expedition to Australia he criticised the settlers’ cruel treatment of black swans, which were trapped and killed in large numbers for their downy under-feathers, for use in pillows and other insulation.

You learned to produce taxidermied bird skins at Queensland University –could you describe this process briefly? Do you view taxidermy as a rather morbid practice?

Not at all. A bit strange and smelly by all means. A strong stomach is required. I took a behind the scenes tour of the Queensland Museum’s zoological collection, thinking that this would be a great opportunity to view the scientific side of taxidermy, and also to see some taxidermied birds up close. The preparation of scientific birdskins for the musuem’s collections are carried out by volunteers. At the end of the tour, one of them challenged me to come along and learn more about taxidermy. And so I became a volunteer trainee bird-stuffer – as they referred to it in the 19th century – submitting myself to the pungent and visceral task of preparing scientific study skins.

I would enter the zoological vertebrate laboratory of a Wednesday morning and take up my stool at a shared worktable. Neatly arranged at my place was a stuffing kit—toothbrush, Dacron (more commonly used to stuff mattresses), paper towels, cornflour, clamps, forceps, scalpel, bonecrusher—and a plastic bag containing a thawed specimen from the museum’s enormous storage freezer: a black-shouldered kite, a barn owl or grey petrel, its thick skin making it easier to remove the body or ‘meat’, as Gould’s stuffers referred to a specimen’s tissue and bones. Slicing into skin, removing muscle and fat, separating joints and scraping ligaments from bone, with my hands and senses I learned the processes John Gould followed to prepare specimens for Elizabeth to sketch.

Which illustration of Elizabeth’s is the most brilliant?

I have to say my favourite illustration is the resplendent quetzal, a trogon from Central America. To this day the Guatemalans still name their currency after the species. Elizabeth illustrated the resplendent quetzal from a stuffed skin around 1836, and I devoted part of a chapter to exploring her almost mystical experience in attempting to capture and paint a faithful likeness of this incredible bird. Quetzals were believed to have magical qualities by the ancient Mayans and were revered as living gods. It was forbidden to kill a quetzal and only the most powerful chiefs were permitted to wear its glorious tapering tail feathers. High priests travelled into the remote cloud forests to capture the males and pluck tail feathers before releasing them to grow more.

It was a challenge to render the brilliance of the resplendent quetzal in words so I’m happy to say that readers of The Birdman’s Wife can fully appreciate the beauty it beauty by seeing Elizabeth’s painting in the endpapers. We have also featured it on a bookmark.

What are some of your favourite Australian bird species to observe? Is there a particularly rare species on your bird-watching bucket list that you’d be thrilled to spot in the wild?

One of my favourite Australian birds, the beloved and easily recognisable superb fairy wren – the male has such an iridescent blue and black upper body – is featured as the cover of The Birdman’s Wife, as well as on the cloth cover of the case of the book.When researching the novel at the John Gould Ornithological Collection in the Spencer Research Library in Kansas, I came across the original pencil design that Elizabeth made of the beautiful species. I love the life in the lithograph, the male bringing a worm to the juvenile in its nest, and think it’s a great example of Elizabeth’s illustrative genius.

One of the most fun parts of birdwatching is using it as an excuse to travel to remote places. I once drove 800 kilometres west of Brisbane to a bird sanctuary to see four of our magnificently coloured arid parrots: the mulga, the ringneck, the pink cockatoo and Bourke’s parrot. I have a chapter in The Birdman’s Wife about a funny little bird known as the plains wanderer. It’s a rare species, found in arid South Australia, and has an ancient lineage with no living relatives. It was only recently, with the aid of DNA, analysis that ornithologists were able to agree upon its classification in the taxonomic tree of birds. I would dearly love to see this strange little critter in the wild.

Could you share with us a favourite sentence or teaser paragraph from The Birdman’s Wife?

‘Drawing was my central preoccupation: perfecting my designs directed the compass of my hours. Pencils, my sloped desk, a study skin, its eyes replaced by cotton wool, were all the materials I required. The plumage brushed and set in place, I flipped the specimen onto its back and sketched the feet, imagining the creature flitting about, incubating eggs, defending territory. Later, as I grew accustomed to my subject’s morphology and was ready to experiment with composition, I mused on other thoughts. My mind drifted. For a time I was so taken by the work of looking – of switching my eyes from the materiality of the bill to the intricacy of the cere – little else existed. It was a kind of marvelling, because in trying to replicate a bird’s form with my brush, I came to admire and to know it. I painted and I studied and, in this constant striving, became me.” (pp. 329)

The Birdman’s Wife is published by Affirm Press.

Source: Meet the woman responsible for John Gould’s Fame Good Reading Magazine

AUTHOR OF THE MONTH: Melissa Ashley

Thank you ausromtoday.com for featuring me on your gorgeous website.

AUTHOR OF THE MONTH: Melissa Ashley What at first began as research for a PhD dissertation on Elizabeth Gould has now eventuated into your debut novel, The Birdman’s Wife. What sparked…

The Birdman’s Wife has landed!

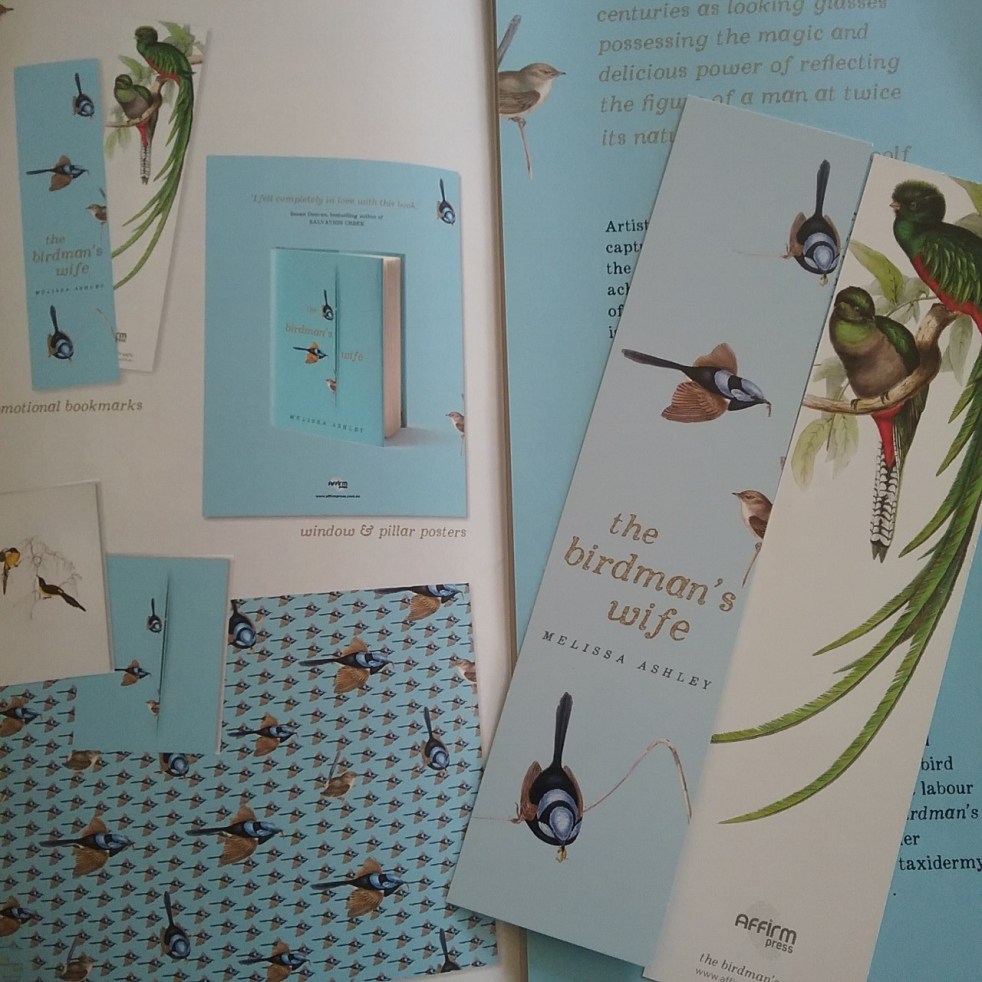

Merchandise!

On Friday I received the fantastic news that The Birdman’s Wife has come back from the printer. A copy for me has been express posted to my address, due to arrive either Monday or Tuesday. All writers know the excitement of waiting for their contributor’s copies to turn up–dented, rain-damaged, flawless–listening out for the postie, trying not to be distracted beavering away on a new project. Grants, offers, cheques, contracts, they all arrive via post. When I was younger, notification of publication or rejection was received by snail mail too, and I became unconsciously tuned to the red and fluoro yellow flash of the postie. I knew I was being productive when I was listening out all the time. It always feels great to have a few pieces circulating.

So of course, today, amongst various jobs, I had an ear out. The postie came by at 12.30 to deliver a bank statement and some propaganda from the council. Disappointed but not surprised, I went back to marking. What would you know, but half an hour later, a second postie bike flashed by and then stopped, idling before the postbox, digging about in his panniers. This time a parcel was left behind.

The gods had smiled on me! I waited until he was out of sight and then closed the computer and straightened my dress. No matter what, I said to myself, you’ll remember this moment forever. Are you ready? My stomach flipped as I opened the door, no doubt whatsoever in my mind that my book was here. What would it look like? Would it be all I had dreamed of and more? Should I take a photo of the unopened packet for posterity?

Just do it, I said to myself. You don’t need to share every-bloody-thing! This one’s for you.

I opened the letterbox and lifted out a smallish package. Hmmm. Wasn’t it supposed to be a bit bigger? I checked the sender’s address: it was from my publisher. I bent the packet this way and that -my book’s a hardcover- and it flexed! Hmmm.

The wait (the second most important trait of a writer) continues. With any luck, The Birdman’s Wife will be in my hot little hands tomorrow. In the meantime, my wonderful publisher has sent me some merchandise to enjoy, which of course I can’t resist sharing.

“Marilyn’s Feast”: Review of Australian Fiction

It’s lovely to have a new piece of fiction published. It’s been a long time. Check out the latest issue of Review of Australian Fiction, Volume 19, Issue 4, for my short story: “Marilyn’s Feast.”

It’s lovely to have a new piece of fiction published. It’s been a long time. Check out the latest issue of Review of Australian Fiction, Volume 19, Issue 4, for my short story: “Marilyn’s Feast.”

Thanks to Inga Simpson for partnering with me.

Marilyn’s Feast (preview)

Marilyn’s Feast (preview)

Marilyn scanned the labels for additives and chemicals but the ingredients lists were equally full of rubbish. How about a visual test? No such luck: the two vacuum-packed slices of prosciutto seemed identical. There was always the supermarket’s deli, though the thought of all that raw pink chicken and soft white fish jumbled amongst the cold cuts had her picturing salmonella cultures, listeria. She supposed she could drive to The Stuffed Truffle, get some freshly sliced. Was that going overboard?

A yellow tag beneath Coles’ gourmet range caught her attention. They were on special—still expensive. Bugger it. She grabbed three packages and crossed prosciutto off her list. In the meat aisle she chose the bulk pack of rump steak. Her recipe called for gravy beef, but the last time she used gravy beef she’d spent ages chopping out the gristly bits, dumping them in a plastic bag which she shoved into the bowels of the freezer. An attempt at environmental awareness had her boil it down for stock—waste not want not—but a foamy-scunge floated to the top of the saucepan and it smelt repulsive and she’d ended up flushing it down the toilet.

The bill amounted to a small fortune, the clerk passing her the long, carefully folded docket, which she screwed into a ball and threw under the cigarette counter.

John need never know.

She ordered lilies from the florists and at the liquor barn a mixed dozen of red, white and bubbly, plus a carton of discounted Mexican beer. In the car park she had trouble closing the boot and had to rearrange several of the environmental bags.

Her phone buzzed and she jerked to a stop at an orange traffic light, the driver in the car behind beeping his horn. She flipped open the casing but it was too late; the call had gone to voice mail. In the darkness of the garage she retrieved the text: Buster head cold. Have 2 cancel L. Nerves soured her stomach. What was she to do with all the alcohol? The extra food? She was ridiculous, out of control. The engine ticked like a timer about to go off but she stayed clipped into her seat, wondering if John would take the initiative and come out and help her unload.

Outside the study she smoothed her cords and shirt, jiggled the doorknob.

John was on Facebook. ‘There’s beers in the car,’ she began. ‘Not to mention a shit-load of heavy groceries.’

A tiny muscle in his cheek popped.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I didn’t mean to be rude. I’m just stressed about tonight.’

John stretched, his blue t-shirt revealing his navel hair. He shut the laptop.

‘You know I hate having to ask.’ She tasted sweat above her lips.

He came at the doorway side-on, all hip and shoulder and defence; she flattened herself against the frame, stomach pulled in tight, to let him through.

She shambled after him, a flightless bird, aware of her thighs rubbing, the elastic of her underpants slicing into her hips, feeling like her flesh had no borders. ‘I’ll get lunch ready, okay? Would you like a cup of tea?’

She was yet to print the online olive tapenade recipe. She dashed back to the computer, patting the mouse and making the screen flick to life. John had forgotten to log himself out of Facebook. Curious, but unaware of making any decision, she found herself – hand on mouse, eyes on screen – scrolling John’s friends. His writer buddies posted an awful lot—links to publishing news items, word counts, up and coming events, milestones. Below a video, loaded by a television producer mate, was a series of comments by a ‘friend’ called Meggie. Marilyn tried to put a face to the name but couldn’t remember John ever talking about her. Something in the postings’ gushy tone made her uneasy.

She listened down the hallway—John was still bringing in groceries—and with her left foot shut the door. Clicking onto the tab for ‘Messages,’ she worked her way down the screen until she came to Meggie’s thumbnail. Most of the thread’s commentary was inane. The girl was a student of some kind. She paged back to the original email:

Hi John, it was great to see you the other day. Thanks for making the effort to come over, I appreciated it. Thanks, also, for talking shop. It’s good to get some expert opinion. And support.

A few entries later, she discovered another post. For five minutes she read and calculated and tallied, piecing together scraps of detail until she had the meeting narrowed down to a particular afternoon last May. It was the first day of John’s week off and he’d mentioned several times that he wanted to go shopping for his friend Clayton’s fortieth birthday. It was so out of character she’d wondered if he wasn’t organising a surprise for her. But when he got back and she asked what he’d bought, the expression on his face was vague. He said he hadn’t found anything yet, that he’d have to have another look. She’d given the incident no further thought.

“As for me, most days I make an effort to do good.”

“Thanks, for the trouble you took from her eyes, I thought it was there for good, so I never tried.”

My daughter and I always squabble about which music to play during the drive to school. I made her suffer Jeff Buckley’s Hallelujah this morning, tired of repeats of the Hill Top Hoods’ Nosebleed Section. Waving me goodbye, I watched her move off, thinking of friends, swaying from side to side as she walked. I studied her, as I often do. How she looks at me. How she negotiates a sharp curve. Her clinging to me at the shopping centre. Two years ago, we discovered that she is losing her eyesight. She can no longer read, resorting to audio texts to get her through class lessons. To put herself to sleep at night. Like me. But her peripheral vision is still strong enough for her to navigate the familiar grounds of school.

My daughter turned twelve this week, and her enjoyment of the attention lavished upon her has been unexpected. My sisters and brother started their families at the same time, six years after my son was born. My children’s seven cousins are aged from 9 months to 3 years. For the last year or so, whenever our families gathered together, my daughter would disappear into another room or space, lost and confused, unable to speak and interact. At her birthday picnic on Sunday, one of those perfect Brisbane August days, her laughter tinkled out over the river. She lay on her stomach in the grass, eyes closed, enjoying the sun on her hair. She horsed around as her cousins climbed on her back, doing their best to squash her, toppling off.

Driving home this morning, inspired by Buckley, I played Famous Blue Raincoat, realising that, after the two most difficult years of my life, my emotions have settled enough for me to contemplate the future. I have spent so many moments at the steering wheel crying. Eagle-eyeing my daughter through the day, trying to comfort her late at night, swallowed by the immensity of her loss. I could only take it in in pieces. It’s the reflection, the acceptance and regret in Cohen’s song that gets me.

And what can I tell you my brother, my killer

What can I possibly say?

I guess that I miss you, I guess I forgive you

I’m glad you stood in my way

Cohen’s song made me order a novel from overseas, several years ago, by Samantha Harvey. Dear Thief. It was, by far, the best book of that reading year. A story of betrayal inspired by Famous Blue Raincoat.

“I suppose the world is constantly producing things of wonderment, every moment, at every scale, and one time in every million or so our minds will be such that we are open to seeing it. To see the silver effervescing of the dust was as beautiful a sight as any mountain or waterfall; but then, when I saw it, I was in love and as happy as a human being can be. Or course this helped. The world is heavily changed by the way we perceive it; in all my reticence and doubt, this is one thing even I haven’t been able to dispute.”

Samantha Harvey, Dear Thief

Each morning, directed by my psychologist, I am supposed to record my mood, to help gauge if I have to intervene with a bath, meditation, a call to a friend, a walk by the river, it’s a brace to hold me back from falling. My relationship broke down too. It was a long one, and, although I was proud that I could keep going, underneath I was deeply shocked. All I had known and thought secured, had suffered a terrible shift. My son’s home from school today, sick with a hacking cough and high temperature. He needs me. And that’s okay. I can be there for him. I haven’t been anywhere for so long that the return is extraordinary.

An (almost) unbearable wait

In the lead up to the publication of my first novel, I’ve attempted to keep sane by easing myself every now and again into the murky waters of a new writing project. It hasn’t been easy, in the midst of a tight editing and publicity schedule, to find the necessary mental space to contemplate, let alone begin, the obsessive process of coaxing a new work to life.

I’m a slow writer. Fast, when I have the idea sorted out, be it the outline, the chapter, the character sketch, but in the lead up to these flurried bursts of keyboard tapping, there are months, weeks, years – Toni Morrison calls it ‘playing in the dark’ – of uncertainty and unease. The requirement of much patience, of inventive healthy (and no-so much), antidotes to that humming motor of anxiety. What surprises me, over and over, are the number of possibilities for the next big project that need to be sifted through before I can settle upon the one that has all of the required parts.

I’m a slow writer. Fast, when I have the idea sorted out, be it the outline, the chapter, the character sketch, but in the lead up to these flurried bursts of keyboard tapping, there are months, weeks, years – Toni Morrison calls it ‘playing in the dark’ – of uncertainty and unease. The requirement of much patience, of inventive healthy (and no-so much), antidotes to that humming motor of anxiety. What surprises me, over and over, are the number of possibilities for the next big project that need to be sifted through before I can settle upon the one that has all of the required parts.

Because I’m a stickler for research, it takes me at least six months of immersion in a subject before I’m even ready to contemplate plot. Before I start writing, I feel a strong need to take an indefinite holiday or go on wild shopping sprees (I hate shopping). And, once I have completed a draft, I need nine months’ or so of a break – teaching, catching up on contemporary novels, daydreaming, being a mum and friend – before building the confidence to return to the raw file.

I have to keep other pieces of writing on the go, to stop losing confidence, to stop mourning the months of scant production. Will I ever write again? Have I forgotten how? I write essays, short stories, once upon a time I wrote poems, but no more, as I pan and filter for the next big project.

Writing’s a funny old beast in that you continually relearn, or is it re-experience? – how it actually works. It’s tricky and slippery, there’s no forcing a chapter or scene when it’s not quite ready, but when that little firefly of readiness appears, all must be put aside to follow its jagged flight.

To arrive at a point of confidence in committing to a new project I need to be utterly sure I can sit with the themes, story, setting and characters for several years. In the last four years I’ve contemplated writing a memoir, which I have fully outlined and made copious notes for, an on-the-road contemporary novel about a woman fleeing her life, which I wrote 60,000 words of a draft before deciding not to resuscitate. And, a historical novel I thought about researching before I began the novel I have recently finished. The setting is late 17th century France. The characters are a group of aristocratic women who contributed to the development of the novel, the memoir, the travel narrative, and the literary fairy tale. They were best-sellers in their day, their books translated into other languages, and published in many editions. But in the Enlightenment these women’s extraordinary texts were slowly erased from the canon. Which of course only makes their histories more tantalising, their adventures and narratives more compelling. I’m looking forward finding their pearls and fountains and ogres and spells and oranges and towers and rubies and fairies.

![160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca[1][1]](https://melissaashley.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca11.jpg?w=274&h=361) I do think the memoir project is a keeper, though not for now. The on-the-road jag is dead to me. But the novel of the Sun King and the Old Regime, keeps flashing in the peripherals of my daily life; as I fall asleep, as I drive, drinking a glass or wine (or two), reading my students’ drafts, such that I’m going to give it a chance. I’m saying yes to its long courtship. For it has everything and more to keep me occupied, entertained. After a long wait, I’m thrilled to be back to my desk, the agony (I do not exaggerate) of midwifing my first novel forgotten, eager to fill in some new blanks.

I do think the memoir project is a keeper, though not for now. The on-the-road jag is dead to me. But the novel of the Sun King and the Old Regime, keeps flashing in the peripherals of my daily life; as I fall asleep, as I drive, drinking a glass or wine (or two), reading my students’ drafts, such that I’m going to give it a chance. I’m saying yes to its long courtship. For it has everything and more to keep me occupied, entertained. After a long wait, I’m thrilled to be back to my desk, the agony (I do not exaggerate) of midwifing my first novel forgotten, eager to fill in some new blanks.

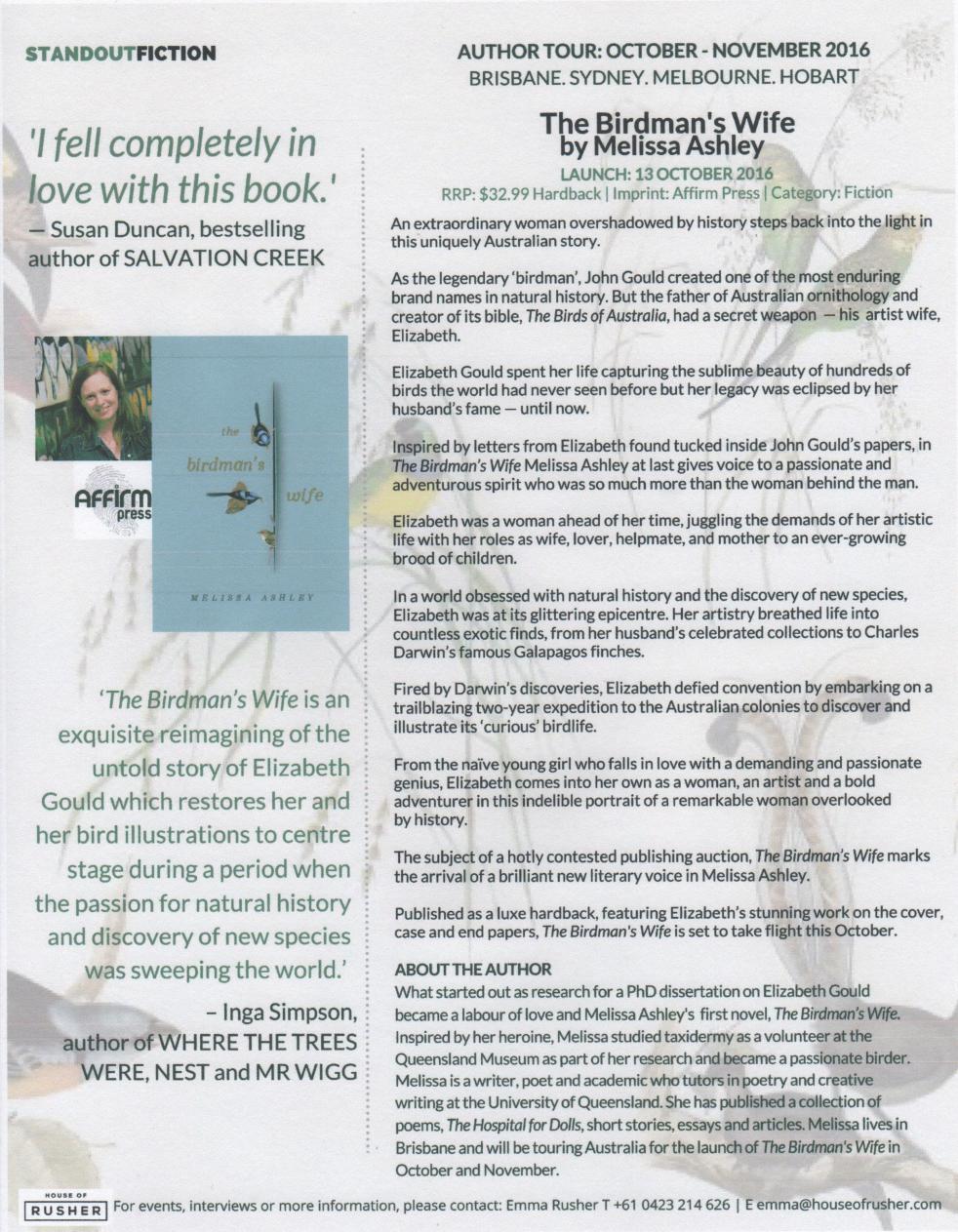

The Birdman’s Wife

Affirm Press, October 2016

ISBN 9781925344998

Pre-order at Simon & Schuster

John Gould created the most magnificent works on birds the world as ever seen. But the celebrated ‘birdman’ had a secret weapon – his artist wife, Elizabeth. Inspired by a diary found tucked inside her famous husband’s papers, The Birdman’s Wife imagines the fascinating inner life of Elizabeth Gould, who was so much more than just the woman behind the man.

Elizabeth Gould was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover and helpmate to a passionate and demanding genius, and as a devoted mother who gave birth to eight children. In a society obsessed with natural history and the discovery of new species, Elizabeth Gould was at its glittering epicentre. Her artistry breathed life into hundreds of exotic finds, from her husband’s celebrated discoveries to Charles Darwin’s famous Galapagos Finches.

Elizabeth Gould was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover and helpmate to a passionate and demanding genius, and as a devoted mother who gave birth to eight children. In a society obsessed with natural history and the discovery of new species, Elizabeth Gould was at its glittering epicentre. Her artistry breathed life into hundreds of exotic finds, from her husband’s celebrated discoveries to Charles Darwin’s famous Galapagos Finches.

Fired by Darwin’s discoveries, in 1838 Eliza defied convention and her own grave misgivings about leaving all but one of her children behind in London in the care of her mother by joining John on a trailblazing expedition to the untamed wilderness of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales to collect and illustrate Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.

Fired by Darwin’s discoveries, in 1838 Eliza defied convention and her own grave misgivings about leaving all but one of her children behind in London in the care of her mother by joining John on a trailblazing expedition to the untamed wilderness of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales to collect and illustrate Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.

From a naive and uncertain young girl to a bold adventurer determined to find her own voice and place in the world, The Birdman’s Wife offers an indelible portrait of an extraordinary woman overlooked by history, until now.

Sneak Preview: Sumptuous Artwork

The Birdman’s Wife: Artwork

In her eleven year career working as principal artist for her husband John Gould, Elizabeth Gould drew, painted and lithographed some 650 hand-coloured lithographs to illustrate the couple’s magnificent folios, featuring many of the world’s most beautiful bird species. Elizabeth, who was not a professionally trained artist, learned lithography from Edward Lear, who not only invented the limerick but was also one of the greatest natural history illustrators of the time. In discussing Elizabeth’s artworks, I had many requests and suggestions that it would be wonderful to include some of her hand-coloured lithographs in my novel.  My dream for more than a decade, was to have a novel published. I am very fortunate to have signed with Affirm Press, who have worked tirelessly — many, many thanks to Christa Moffett, Karen Cook, Kathryn Lafferty and Fiona Henderson — for all the work you have put into finding, funding and designing these exquisite endpages featuring the artworks of Elizabeth Gould. (The indigo macaw is Edward Lear’s.) I could not be more pleased and excited!

My dream for more than a decade, was to have a novel published. I am very fortunate to have signed with Affirm Press, who have worked tirelessly — many, many thanks to Christa Moffett, Karen Cook, Kathryn Lafferty and Fiona Henderson — for all the work you have put into finding, funding and designing these exquisite endpages featuring the artworks of Elizabeth Gould. (The indigo macaw is Edward Lear’s.) I could not be more pleased and excited!

The Birdman’s Wife will be produced in hardcover, the inside cover featuring Elizabeth Gould’s complete hand-coloured lithograph of the superb fairy wrens and their young, which are shown flying out of the front cover on the dust jacket. I can’t wait to have the final copy in my hot little hands! Please enjoy!