Last week I had the great privilege of being invited to perform as an artist at the 2017 Perth Writers’ Festival (23-26 February) to promote my first novel, The Birdman’s Wife, put into print by the incredible independent Australian publisher, Affirm Press.

I have been very lucky in being invited to speak at a huge range of gigs: Newtown Festival; The Big Bookclub at the Avid Reader; Riverbend Books; QLD Museum; Mitchell Library; Farrells’ Bookstore in Hobart; Book Face; and a local environmental group. These events went really well (to my nervous relief). Terrified of public speaking, I was surprised to discover much enjoyment in signing books and meeting readers, discovering their various links to Elizabeth Gould’s story. Some were bird-watchers, some historians, others artists in their own right.

I have been very lucky in being invited to speak at a huge range of gigs: Newtown Festival; The Big Bookclub at the Avid Reader; Riverbend Books; QLD Museum; Mitchell Library; Farrells’ Bookstore in Hobart; Book Face; and a local environmental group. These events went really well (to my nervous relief). Terrified of public speaking, I was surprised to discover much enjoyment in signing books and meeting readers, discovering their various links to Elizabeth Gould’s story. Some were bird-watchers, some historians, others artists in their own right.

Having spent many years (too many to confess) as an eager punter at writers’ festivals, someone who would look in awe at the authors’ taking up each panel and speaking intelligently and eloquently about their books, I used to wonder at their nerves. I panicked, fearful of how they managed to follow each others’ conversations, how they weren’t intimidated by the huge crowds, how they didn’t have a nervous breakdown before and after each event.

To prepare myself, I read all of the books of my fellow panelists, supplied by their publishers. I had no idea being a published writer entailed such perks. But, come the week I was flying to Perth, I felt myself consumed by a horrid stomach-full of nervous energy.

To prepare myself, I read all of the books of my fellow panelists, supplied by their publishers. I had no idea being a published writer entailed such perks. But, come the week I was flying to Perth, I felt myself consumed by a horrid stomach-full of nervous energy.

The first way that I spoke back to such intense emotion was to go shopping. New dresses, new earrings, hell, a new handbag even, to match my shoes. I couldn’t quite concentrate on my writing in the days precipitating my flight.

It was my first visit to Perth, and the festival organisers were brilliant, securing a lovely hotel room, shuttle buses, cash for food, and a bunch of other writers to get to know. Before my first gig, I met the beautiful Nadia L King, author of Jenna’s Truth, blogger, reviewer, instagram star and all-round supporter of writers.

The following day, I was so nervous about my impending first conversation, with the erudite Bernice Barry, author of a biography on Georgiana Molloy, a 19th century botanist from Western Australia, I wasn’t sure if I would make it to the outdoor space where I was to perform. And it was really hot, the 36+ degree temperature (not unlike the whole of Brisbane’s heatwave summer) following me all the way to Perth.

The following day, I was so nervous about my impending first conversation, with the erudite Bernice Barry, author of a biography on Georgiana Molloy, a 19th century botanist from Western Australia, I wasn’t sure if I would make it to the outdoor space where I was to perform. And it was really hot, the 36+ degree temperature (not unlike the whole of Brisbane’s heatwave summer) following me all the way to Perth.

To my great relief and gratitude, Martin Hughes, CEO of Affirm Press, flew in to accompany me, to talk me up and talk down my nerves before I stepped in front of the microphone and crowds. My first gig was a full house and it went well, despite my discomfort at being out of a familiar place, and several paramedics turning up 55 minutes into our conversation to cart off several members of the audience who had succumbed to the heat. We stopped immediately, though I felt concerned about the temperature forecast for the following day: over 40 degrees.

As if in some sort of compensation, an audience member had sketched Bernice, Barbara Horan, our lovely chair, and myself, while we spoke. Afterwards, the artist came up to the stage and introduced herself, asked us all to autograph her sketch. What a gift.

I signed a few books, and then scurried away for a cigarette, my rapidly beating heart slowed, at least for the moment. I had a great dinner with Martin, laughs and drinks, all precipitated by a confused wander through the streets of Perth’s CBD (neither of us has much of a sense of direction).

I signed a few books, and then scurried away for a cigarette, my rapidly beating heart slowed, at least for the moment. I had a great dinner with Martin, laughs and drinks, all precipitated by a confused wander through the streets of Perth’s CBD (neither of us has much of a sense of direction).

Nevertheless, I couldn’t sleep much that night. I worried incessantly about my two gigs the following day. One of which was with my literary heroine, Hannah Kent. Would I turn to jelly in her presence? And then I moved on and fixated on the belief that I was not comfortable talking about The Birdman’s Wife without notes for the proscribed ten minutes the panel required. Once our chair, the lovely Geraldine Blake, and Martin reassured me that I could present in the manner which made me most comfortable, my nerves gripped onto another unknown. Due to the fame of Hannah, I panicked that we were about to perform in an indoor Roman arena. Would I get ‘the chokes’ like Howard Moon from The Mighty Boosh and humiliate myself entirely? Or fall over a mike lead or spill my water and electrocute Hannah or some other unanticipated embarrassment? Exposed as a buffoon, the butt of everyone’s jokes.

Somehow — it really is a blur –I got a hold of my nerves and turned up the following morning to meet Hannah Kent, author of Burial Rites and The Good People. To gush over Jessie Burton, writer of the bestselling novels The Miniaturist and The Muse. I sweated in a most unladylike fashion in their company, pressing my legs together (the toilet line was looong), trying to not fan-girl them too badly. Though I could not help raving about their mastery of structure, plot, dialogue, character, lyricism. When I stilled my jabbering jaws, I marvelled as they engaged in pre-gig laughs about jetlag from visiting Iceland, New York. I nodded and grinned, trying to not appear insane, shaking hands pinned behind my back.

Jessie-a trained actor-and Hannah, a consummate writer – spoke with intelligence, respect, humour and openness. I was proud that I managed to not stumble my own answers to Geraldine’s questions. I felt the warmth in the room that lit up their fans, turned out to see their favourite writers in the flesh. Afterwards, we traipsed over to the book-signing room; Martin reckoned I smashed it, and I felt pretty chuffed that I managed to save face. That was until the extraordinary Clementine Ford (deep bows) arrived and I noted that I was seated between her beautifully fierce self and my literary crush, Hannah Kent. Luckily my hand-bag carrier/publisher was lurking, and bade me make a hasty exit.

Both evenings I had dinner with my publisher. I think I told him about five times that I signed with Affirm Press because of their manifesto of building a relationship with their writers. They have integrity, guts, and are willing to take a risk with somebody whose writing they believe in. That evening, apart from trawling half of Perth’s CBD in search of a restaurant, I learned much about publishing, book sales, prizes, and literary passion. I returned to my hotel feeling looked after and reassured. Affirm Press believed in me.

Both evenings I had dinner with my publisher. I think I told him about five times that I signed with Affirm Press because of their manifesto of building a relationship with their writers. They have integrity, guts, and are willing to take a risk with somebody whose writing they believe in. That evening, apart from trawling half of Perth’s CBD in search of a restaurant, I learned much about publishing, book sales, prizes, and literary passion. I returned to my hotel feeling looked after and reassured. Affirm Press believed in me.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t long before my anxiety reared up and grasped me by the throat. To calm my nerves, Martin distracted me by asking about the poem I loved best in all the world. It was in fact resonating through my brain all weekend, written by the maddest of mad poets, Robert Lowell. I dare not share Waking in the Blue (my real favourite) and instead confessed a penchant for the mysterious Skunk Hour:

Skunk Hour

For Elizabeth Bishop

Nautilus Island’s hermit

heiress still lives through winter in her Spartan cottage;

her sheep still graze above the sea.

Her son’s a bishop. Her farmer

is first selectman in our village,

she’s in her dotage.

Thirsting for

the hierarchic privacy

of Queen Victoria’s century,

she buys up all

the eyesores facing her shore,

and lets them fall.

The season’s ill--

we’ve lost our summer millionaire,

who seemed to leap from an L. L. Bean

catalogue. His nine-knot yawl

was auctioned off to lobstermen.

A red fox stain covers Blue Hill.

And now our fairy

decorator brightens his shop for fall,

his fishnet’s filled with orange cork,

orange, his cobbler’s bench and awl,

there is no money in his work,

he’d rather marry.

One dark night,

my Tudor Ford climbed the hill’s skull,

I watched for love-cars. Lights turned down,

they lay together, hull to hull,

where the graveyard shelves on the town. . . .

My mind’s not right.

A car radio bleats,

‘Love, O careless Love . . . .' I hear

my ill-spirit sob in each blood cell,

as if my hand were at its throat . . . .

I myself am hell;

nobody’s here--

only skunks, that search

in the moonlight for a bite to eat.

They march on their soles up Main Street:

white stripes, moonstruck eyes’ red fire

under the chalk-dry and spar spire

of the Trinitarian Church.

I stand on top

of our back steps and breathe the rich air--

a mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail

She jabs her wedge-head in a cup

of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail,

and will not scare.

All weekend, I wanted desperately to connect with my fellow writers but I was so overwhelmed by my professional responsibilities that it was simply not possible. I would have gushed, stuttered and knocked something over — I had already done all of this in front of my work colleague and friend Elspeth Muir, with whom I caught the plane — and decided I would be better off saving myself for the next festival.

By the time I got to my final gig, a conversation with Kate Summerscale, author of The Wicked Boy, a biography of a 13 year old boy who stabbed his mother to death, spent 17 years in a mental asylum and then emigrated to Australia to become a decorated ANZAC medic, my brain had nearly imploded. Despite Susan Wyndham’s excellent facilitation as chair, a week of intense anxiety resulted in a challenging panel. I felt my responses to anticipated questions running away from my consciousness before I had even started speaking. Yes, I rambled somewhat.

I burst into embarrassing tears following my last panel, and yet, despite my red eyes and blubbering, I felt as if I had pushed myself to the very limits of my abilities with regard to public speaking. I was sorta proud, despite my feelings of utter humiliation. I think many writers feel this. It’s just how we are.

I burst into embarrassing tears following my last panel, and yet, despite my red eyes and blubbering, I felt as if I had pushed myself to the very limits of my abilities with regard to public speaking. I was sorta proud, despite my feelings of utter humiliation. I think many writers feel this. It’s just how we are.

That evening I had a few too many (deserved) champagnes, which led to a remarkable opportunity. I hung out with Deng Adut, a former child soldier from South Sudan who runs a human rights legal practice and has been honoured as a New South Welshman of the year, one of the real superstars of the festival.

All in all, my first writers’ festival was an incredible experience. I’m still thinking about it three days later. At the airport, I ran into Elspeth Muir, author of Wasted, a memoir about alcohol consumption in Australia and a family tragedy, recently long-listed for the Stella Prize, who I work with at the University of Queensland. It seems my intense nerves are not unique. We commiserated about speaking alongside literary superstars, about our guts and relief, laughing, spilling coffee, giggling and riffing off one another, so much so that we almost missed our flight home.

I have several more festivals this year, and am so relieved I survived my first. An initiation in no small sense of the term. Six months ago, after ten years’ effort, I published my first novel. It was a labour of love, and I thought that once I had got on the other side of the publisher’s door, all would be well. Little did I know that a whole other world of sales and publicists and editors and talks lay in wait. But I did it. I’m not sure if I will ever be totally comfortable with public speaking. But I’m still here, I signed a few books and my heart’s still beating. Next time, I’ve decided, I’m going to meet some writers!!

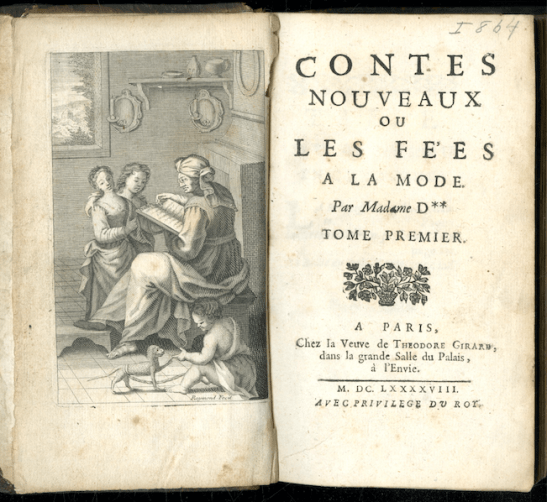

Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy — who’d been married off at 15 to an abusive man three decades her elder — slipped messages of resistance into her popular stories, risking jail in the process.

Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy — who’d been married off at 15 to an abusive man three decades her elder — slipped messages of resistance into her popular stories, risking jail in the process.

![160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca[1]](https://melissaashley.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca1.jpg?w=242&h=319) Most revolutions begin quietly, in narrative. Take, for instance, fairytales. The popular understanding is that fairytales evolved exclusively from oral folktellers – from the uneducated “Mother Goose” nurse, passing into the imaginations of children by centuries of fireside retellings.

Most revolutions begin quietly, in narrative. Take, for instance, fairytales. The popular understanding is that fairytales evolved exclusively from oral folktellers – from the uneducated “Mother Goose” nurse, passing into the imaginations of children by centuries of fireside retellings.

I have been very lucky in being invited to speak at a huge range of gigs: Newtown Festival; The Big Bookclub at the Avid Reader; Riverbend Books; QLD Museum; Mitchell Library; Farrells’ Bookstore in Hobart; Book Face; and a local environmental group. These events went really well (to my nervous relief). Terrified of public speaking, I was surprised to discover much enjoyment in signing books and meeting readers, discovering their various links to Elizabeth Gould’s story. Some were bird-watchers, some historians, others artists in their own right.

I have been very lucky in being invited to speak at a huge range of gigs: Newtown Festival; The Big Bookclub at the Avid Reader; Riverbend Books; QLD Museum; Mitchell Library; Farrells’ Bookstore in Hobart; Book Face; and a local environmental group. These events went really well (to my nervous relief). Terrified of public speaking, I was surprised to discover much enjoyment in signing books and meeting readers, discovering their various links to Elizabeth Gould’s story. Some were bird-watchers, some historians, others artists in their own right. To prepare myself, I read all of the books of my fellow panelists, supplied by their publishers. I had no idea being a published writer entailed such perks. But, come the week I was flying to Perth, I felt myself consumed by a horrid stomach-full of nervous energy.

To prepare myself, I read all of the books of my fellow panelists, supplied by their publishers. I had no idea being a published writer entailed such perks. But, come the week I was flying to Perth, I felt myself consumed by a horrid stomach-full of nervous energy.

The following day, I was so nervous about my impending first conversation, with the erudite Bernice Barry, author of a biography on Georgiana Molloy, a 19th century botanist from Western Australia, I wasn’t sure if I would make it to the outdoor space where I was to perform. And it was really hot, the 36+ degree temperature (not unlike the whole of Brisbane’s heatwave summer) following me all the way to Perth.

The following day, I was so nervous about my impending first conversation, with the erudite Bernice Barry, author of a biography on Georgiana Molloy, a 19th century botanist from Western Australia, I wasn’t sure if I would make it to the outdoor space where I was to perform. And it was really hot, the 36+ degree temperature (not unlike the whole of Brisbane’s heatwave summer) following me all the way to Perth.

I signed a few books, and then scurried away for a cigarette, my rapidly beating heart slowed, at least for the moment. I had a great dinner with Martin, laughs and drinks, all precipitated by a confused wander through the streets of Perth’s CBD (neither of us has much of a sense of direction).

I signed a few books, and then scurried away for a cigarette, my rapidly beating heart slowed, at least for the moment. I had a great dinner with Martin, laughs and drinks, all precipitated by a confused wander through the streets of Perth’s CBD (neither of us has much of a sense of direction). Both evenings I had dinner with my publisher. I think I told him about five times that I signed with Affirm Press because of their manifesto of building a relationship with their writers. They have integrity, guts, and are willing to take a risk with somebody whose writing they believe in. That evening, apart from trawling half of Perth’s CBD in search of a restaurant, I learned much about publishing, book sales, prizes, and literary passion. I returned to my hotel feeling looked after and reassured. Affirm Press believed in me.

Both evenings I had dinner with my publisher. I think I told him about five times that I signed with Affirm Press because of their manifesto of building a relationship with their writers. They have integrity, guts, and are willing to take a risk with somebody whose writing they believe in. That evening, apart from trawling half of Perth’s CBD in search of a restaurant, I learned much about publishing, book sales, prizes, and literary passion. I returned to my hotel feeling looked after and reassured. Affirm Press believed in me. I burst into embarrassing tears following my last panel, and yet, despite my red eyes and blubbering, I felt as if I had pushed myself to the very limits of my abilities with regard to public speaking. I was sorta proud, despite my feelings of utter humiliation. I think many writers feel this. It’s just how we are.

I burst into embarrassing tears following my last panel, and yet, despite my red eyes and blubbering, I felt as if I had pushed myself to the very limits of my abilities with regard to public speaking. I was sorta proud, despite my feelings of utter humiliation. I think many writers feel this. It’s just how we are.

Not long after I sold the rights for The Birdman’s Wife to Affirm Press, I was delighted to be offered a publishing contract from Wavesound, a new audiobook imprint dedicated to making Australian titles available in alternative formats to print. Wavesound is an imprint of Audible, the world’s largest publisher of audiobooks. All of Wavesound’s audiobooks are recorded locally in Sydney, and employ Australian actors.

Not long after I sold the rights for The Birdman’s Wife to Affirm Press, I was delighted to be offered a publishing contract from Wavesound, a new audiobook imprint dedicated to making Australian titles available in alternative formats to print. Wavesound is an imprint of Audible, the world’s largest publisher of audiobooks. All of Wavesound’s audiobooks are recorded locally in Sydney, and employ Australian actors.