I drifted towards the back of the workshop, my attention caught by a menagerie of shorebirds – a godwit, several sandpipers, curlews, dotterels, herons and varities of plover. For a heart-stopping moment the display tricked my eyes. It seemed the birds had flown into the room via a secret passage and, like children, settled before the warmth of the flames in the hope of being treated to a story. But as I drew closer I could see that the birds were perched on wooden boards, each miming its own dramatic scene. The sandpiper probed for molluscs. One of the plovers preened his shoulder. The heron reared to strike. The curlew held a shell in the barber’s tongs of its beak. The darter had drawn his long neck into a loop. (4)

This passage, early in this first novel by Melissa Ashley, displays Elizabeth Coxen’s keen imagination, sensitivity, and observational skills. The reader quickly realises she is a singular figure, a woman of warmth, sympathy, artistic ambition, intelligence. Coxen goes on to become the previously little known wife of John Gould, the famous English ‘birdman’ and naturalist of the nineteenth century. Ashley, a published poet and scholar in creative writing, has given us a picture of what she imagines Elizabeth to be as a human being and a skilled and dedicated artist, and it is a magnificent achievement.

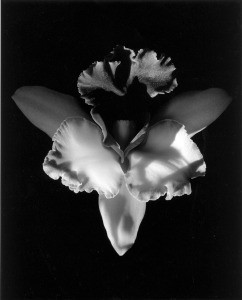

The author has researched her material thoroughly, even becoming a volunteer at the Queensland Museum and learning how to prepare ornithological specimens. This makes her descriptions of the preparations of the birds in her novel thoroughly convincing, as when Elizabeth is required to prepare the body of a brush turkey for its skeleton to be displayed. And the descriptions of her drawing and painting the prepared birds sometimes take the breath away, as with the quetzal, who ‘sported iridescent sheens in its plumage, like silk from China, gossamer and spider’s webs, droplets of water catching the light’ (94). The details of how the work was done, and the ingredients used, remind the reader of how difficult it was: ‘… my powders spilled across the table and I poured in the wrong amounts of water. …. For the yellow I used an Indian pigment made by feeding Brahmin cows the leaves of mango trees, then intensifying the colour of the animal’s urine by adding chemicals’ (96). The hours of work strained her eyesight, made her body ache; her husband drove himself from dawn to dusk as well, but she notes that he sometimes forgot that others did not have his stamina. These personal aspects of her characters are well described throughout.

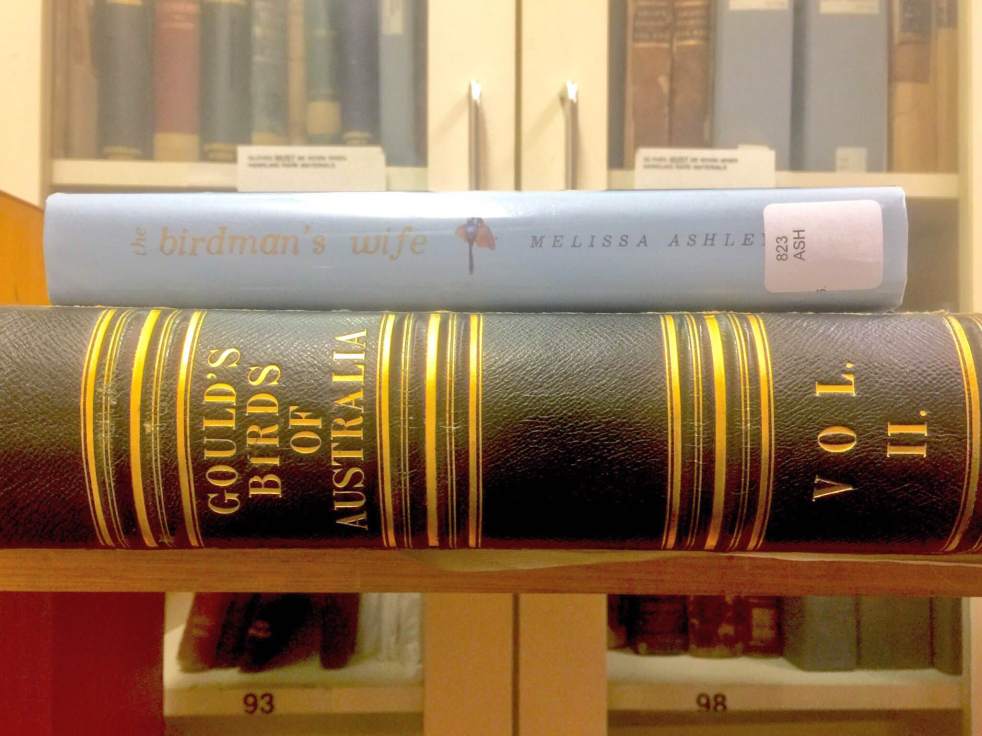

The author explains at the back of her book why she became fascinated by the subject, which began with a poet and his poem about a particular bird, that eventually grew into an interest in Elizabeth Gould through being loaned Isabella Tree’s biography The Birdman: The Extraordinary Story of the Victorian Ornithologist John Gould (1991). Here she learned how important Elizabeth was to Gould’s ambitious goals: she ‘designed and completed some 650 hand-coloured lithographs of the world’s most beautiful bird species’ (378) while also raising a large family, and travelling to Australia for two years to work with her husband on compiling specimens and illustrating them for The Birds of Australia, that extraordinary multi-volumed work of scientific and artistic excellence. But her name and her work were not fully recognised, the lithographs usually being co-signed with her husband, and his name was more prominent generally. He apparently exploited Edward Lear, erasing his name from plates he reproduced for his publications, according to Peter Levi in his Edward Lear: A Biography (1995). But Ashley does not overplay this, preferring to imply the less attractive aspects of Gould’s character and practice through neat and gentle exchanges of dialogue, or the more robust scene towards the end of the novel, when Gould disapproves of the portrait of his wife executed by Richard Orleigh (an invented character as the real portraitist was unknown). It is implied he fears social approbation for allowing his wife to appear in a more active, less feminine role, of earning a living by art, something that might also affront his idea of himself as the provider for the household. This is skilfully accomplished, and shows the reader Elizabeth’s frustration and disappointment with her husband’s attitude, but also her resolution to deal with it by affirmation of her vocation: ‘In my heart, I knew I was an artist, no matter the appearances my husband needed to keep up to meet social conventions’ (327).

The novel follows the life of the couple from 1828, from the moment they meet in their early twenties. Edward Lear features as a much loved drawing companion and friend to Elizabeth, as well as a revered artist, and Charles Darwin praises her work, using a number of her lithographs for his book on the Beagle expedition. We follow them through the major episodes of their life together, including that perilous and demanding trip to and within Australia, but also see the private life through the eyes of Elizabeth. The descriptions of them eating cakes during their courting, the passages showing Elizabeth’s grief at the loss of loved ones, the sheer terror of a storm at sea, the friendship between Elizabeth and Lady Franklin, engender feelings of delight, sorrow, pathos, horror. Ashley knows how to tell a story, develop characters, write involving and natural-sounding dialogue, describe the unusual and the everyday alike.

A feature I noticed was the inclusion, every now and then, of Elizabeth’s reservations about the numbers of birds (and other animals) killed by her husband and his assistants in order to preserve and examine and record them. Another character may remind her that it is for science, and she agrees, but the uneasiness remains. And it passes on to her daughter Lizzie who expresses disapproval at the dead birds arriving at their home after the two year long adventure in Australia. I do not know if the actual Elizabeth Gould expressed these concerns, but it is entirely compatible with her character in this novel that she would. And an interesting reminder, or stretch out to the present times, of our impact on the world and its creatures.

The other novel that I kept thinking of in relation to this one is Mrs Cook: The Real and Imagined Life of the Captain’s Wife (2003) by Marele Day, but of course there are many fictional works written around real figures in history, such as Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell series, and Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang (2000). Some are more fictionalised than others, but Ashley has chosen to maintain the facts as they are known and to give the reader a possible, plausible, and beautifully crafted intimate portrait of Elizabeth Gould, and her vital part in the production of the books under her husband’s name.

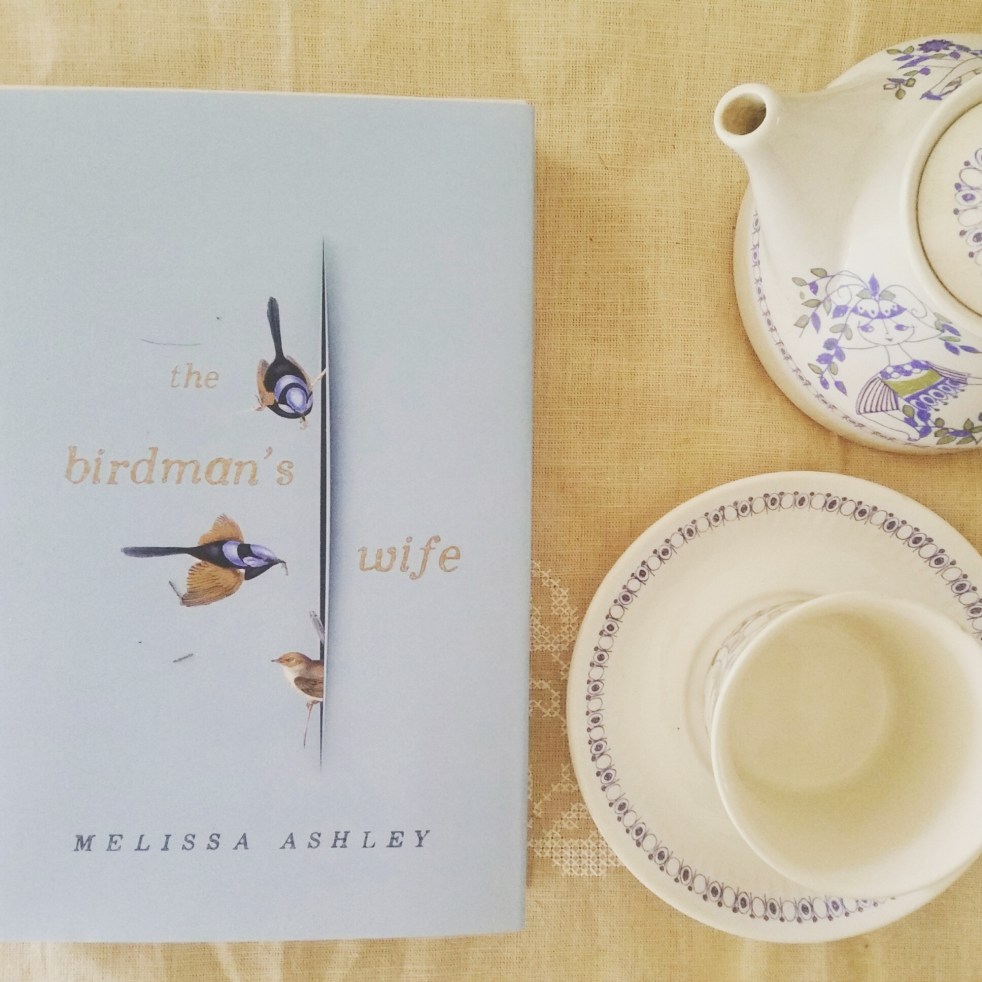

Not only is this book fine fiction, but it is a thing of beauty as an object. It will beckon the reader from the shelves with its pale blue cover featuring fairy wrens, and the surprises when the book is opened and dustcover removed. A fitting production for an outstanding first novel.

http://www.compulsivereader.com/2016/11/05/a-review-of-the-birdmans-wife-by-melissa-ashley/

About the reviewer: Sue Bond is a writer and reviewer living in Brisbane.

The first point I noted about The Birdman’s Wife is that Elizabeth Gould, not her husband John, the famous ornithologist, painted the pictures of birds I knew and loved as a child. While Elizabeth was credited by her initials, alongside John’s, for creating over 650 hand-coloured lithographs for a number of publications, including The Birds of Australia, very little is known about the artist; she was overshadowed by her larger-than-life husband. Melissa Ashley’s task, as she says in an author’s note, is to bring to life, through fiction, what the factual accounts have overlooked.

The first point I noted about The Birdman’s Wife is that Elizabeth Gould, not her husband John, the famous ornithologist, painted the pictures of birds I knew and loved as a child. While Elizabeth was credited by her initials, alongside John’s, for creating over 650 hand-coloured lithographs for a number of publications, including The Birds of Australia, very little is known about the artist; she was overshadowed by her larger-than-life husband. Melissa Ashley’s task, as she says in an author’s note, is to bring to life, through fiction, what the factual accounts have overlooked. Elizabeth’s curiosity about the natural world links her, across more than a century, to Meridian Wallace, the main female character in The Atomic Weight of Love, who goes bird-watching on her own and is not the slightest bit interested in playing with dolls. Meridian is a brilliant student who falls in love with a physics lecturer 20 years her senior, marries and then follows him to Los Alamos, postponing, then finally abandoning her graduate studies in ornithology. In the middle decades of the 20th century, Meridian is not forced to endure successive pregnancies – she never has children of her own – but she submits to the husband with whose intellect she first fell in love.

Elizabeth’s curiosity about the natural world links her, across more than a century, to Meridian Wallace, the main female character in The Atomic Weight of Love, who goes bird-watching on her own and is not the slightest bit interested in playing with dolls. Meridian is a brilliant student who falls in love with a physics lecturer 20 years her senior, marries and then follows him to Los Alamos, postponing, then finally abandoning her graduate studies in ornithology. In the middle decades of the 20th century, Meridian is not forced to endure successive pregnancies – she never has children of her own – but she submits to the husband with whose intellect she first fell in love.

Title: The Birdman’s Wife

Title: The Birdman’s Wife

The Birdman’s Wife is the debut novel of

The Birdman’s Wife is the debut novel of

The spoiler alert in this book review is that it is based on a real-life woman: Elizabeth Gould, the wife of an eminent ornithologist / taxidermist, John Gould. If you look up John Gould, you’ll find his Wikipedia entry, which says, “A bird artist”, describing his monographs as “illustrated by plates that he produced with the assistance of his wife, Elizabeth Gould”.

The spoiler alert in this book review is that it is based on a real-life woman: Elizabeth Gould, the wife of an eminent ornithologist / taxidermist, John Gould. If you look up John Gould, you’ll find his Wikipedia entry, which says, “A bird artist”, describing his monographs as “illustrated by plates that he produced with the assistance of his wife, Elizabeth Gould”.

when I was 19, sitting with 300 psych students making notes on week three’s ‘human sexuality’ lecture. Next to me slouched my best friend and flatmate, with whom I’d taken the previous semester’s ‘philosophy and sex’. We were both, back in then, in our different ways, utterly obsessed with sex. He spent a lot of time in his room, ‘studying’; I went out on the weekends and met boys. For whole evenings we dissected our crushes and pickups on the broken couch in the lounge, while in the kitchen enormous cockroaches scuttled over the water-damaged mustard cupboards for noodle crumbs. I lent him Anais Nin and he photocopied me anthropology papers about polyandry and wife-sharing. For human beings, monogamy was doomed to failure and with our hormone-soaked minds, we whole-heartedly agreed. Not that either of us knew the first thing about it.

when I was 19, sitting with 300 psych students making notes on week three’s ‘human sexuality’ lecture. Next to me slouched my best friend and flatmate, with whom I’d taken the previous semester’s ‘philosophy and sex’. We were both, back in then, in our different ways, utterly obsessed with sex. He spent a lot of time in his room, ‘studying’; I went out on the weekends and met boys. For whole evenings we dissected our crushes and pickups on the broken couch in the lounge, while in the kitchen enormous cockroaches scuttled over the water-damaged mustard cupboards for noodle crumbs. I lent him Anais Nin and he photocopied me anthropology papers about polyandry and wife-sharing. For human beings, monogamy was doomed to failure and with our hormone-soaked minds, we whole-heartedly agreed. Not that either of us knew the first thing about it.