‘Just Kids’, by Patti Smith

I was first introduced to Robert Mapplethorpe  when I was 19, sitting with 300 psych students making notes on week three’s ‘human sexuality’ lecture. Next to me slouched my best friend and flatmate, with whom I’d taken the previous semester’s ‘philosophy and sex’. We were both, back in then, in our different ways, utterly obsessed with sex. He spent a lot of time in his room, ‘studying’; I went out on the weekends and met boys. For whole evenings we dissected our crushes and pickups on the broken couch in the lounge, while in the kitchen enormous cockroaches scuttled over the water-damaged mustard cupboards for noodle crumbs. I lent him Anais Nin and he photocopied me anthropology papers about polyandry and wife-sharing. For human beings, monogamy was doomed to failure and with our hormone-soaked minds, we whole-heartedly agreed. Not that either of us knew the first thing about it.

when I was 19, sitting with 300 psych students making notes on week three’s ‘human sexuality’ lecture. Next to me slouched my best friend and flatmate, with whom I’d taken the previous semester’s ‘philosophy and sex’. We were both, back in then, in our different ways, utterly obsessed with sex. He spent a lot of time in his room, ‘studying’; I went out on the weekends and met boys. For whole evenings we dissected our crushes and pickups on the broken couch in the lounge, while in the kitchen enormous cockroaches scuttled over the water-damaged mustard cupboards for noodle crumbs. I lent him Anais Nin and he photocopied me anthropology papers about polyandry and wife-sharing. For human beings, monogamy was doomed to failure and with our hormone-soaked minds, we whole-heartedly agreed. Not that either of us knew the first thing about it.

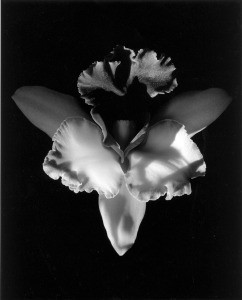

I’ll never forget the high contrast monochrome of Mapplethorpe’s flower photographs. I felt absorbed, excited and enthralled by his blatant celebration of sex organs. The red capillaries in the pitcher plant, the labial folds of the orchid. Plant genitalia conjuring human genitalia, but removed from any interpersonal context. Stripped bare in the studio setting, they appeared vulnerable. Was it their extraordinary interaction with light or was it the fragility of the flowers’ soon to be withered flesh? There was an intimacy in each of Mapplethorpe’s portraits, a stripped back essence that separated the beloved from his parts, that got down to celebrating the basics of attraction and lust and fucking, in whatever its guises. Similes, excerpted from the cultural zones of neurosis and guilt.

Before moving onto Mapplethorpe’s infamous self-portraits, the lecturer gave a preamble, to provide the unformed student mass with a bit of socio-cultural background as to why the photographer depicted himself (a) with devil’s horns, and (b) in BDSM attire with a bullwhip sticking out of his anus. When the slides were finally unveiled, I found myself unmoved by Mapplethorpe’s self-depictions. Having the portrait explained in words before I had the chance to see it, robbed me of the emotional jolt Mapplethorpe wished to provoke. When questioned for a response, my flatmate had little more than a grunt to express his experience. Indeed, when I pestered him further for an opinion he completely clammed up. We were both from Catholic families but were throwing off our upbringings in very different ways. I acted out. He honed the weapons of Western rationalism to cut his way out of the frankincense-thick labyrinth of bodily guilt and denial his religion had trapped him inside. Unlike me, he was innocent, which meant that he had no real way of responding to the portrait’s meaning, his only avenue repression.

I can’t recall if they were shown in the lecture, but in my 20’s I became interested in, if a little intimidated by, Mapplethorpe’s nudes. I loved his project of making the greed for flesh, the energy of lust and libido, explicit. Some of the photographs went too far for my tastes, but others drew me in. I would gaze at a perfectly sculpted deltoid, buttock or abdominal pack for long moments. Not the most subtle young woman, I stuck Black and White magazine reprints of the less provocative nudes all over the walls of my rented room, alongside my painstakingly hand-copied verses of The Wasteland.

Twenty years later, I returned to Mapplethorpe, via Patti Smith’s memoir ‘Just Kids’. I was never a fan of Patti Smith’s music. I didn’t hate it, but I hadn’t grown up a listener and it passed me by. When I sought out Horses, the moment where I might connect had long passed. It was impossible for me to become enthralled, having spent my late 20’s taking in spoken word and slam poetry performances in an endless round of smoky cafes and pubs. In a Vanity Fair article, I’d stumbled upon Smith’s prose, which was poetic and fresh, muscular and surprising. It opened the lock on my interest in her as a writer.

‘Just Kids,’ makes a study of Manhattan in the seventies, of the pre-gentrification neighbourhoods that bohemians, artists and rockers like Smith and Mapplethorpe lived and created in. Arriving in New York, not long after adopting out her infant daughter, Smith was poor and ill resourced, vulnerable and occasionally destitute. She was naïve and dreamy, trusting and intuitive, a natural poet. However she found friends, places to kip, jobs, which over time, became less degrading. Through it all she worked on her art. I loved the openness of Smith’s personality in her willingness to explore any form or media for self-expression, without proper training and instruction, sometimes even without materials. She’d steal, beg and scavenge the baubles, feathers, glues and paints that her projects required.

‘Just Kids’ is everything you want in the memoir of a rock star poet and so much more. The prose is beautifully written and the narrative is authentic, considered, fascinating, generous, and revealing, all the while keeping a little mystery to itself. Many previously unpublished photographs of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, documenting the intimacies of their relationship, are included. I’d read one of Smith’s anecdotes and stare for long moments at the corresponding picture, trying to absorb just what an electrifying couple she and Mapplethorpe made–charismatic, cool, gamine and gauche–all in the one pose. There was a shot of them emerging from a rundown circus on Coney Island; of them lying on a messy bed in their louse-infested apartment in Chelsea; of Smith, alone, surrounded by her favourite objects and items: a piece of jewellery, records, books, a favourite shawl or jacket. I pored over the photographs, as if by gazing at them for long enough, I might connect Smith’s voice on the page with the extraordinary visuals made by her younger self.

An unexpected pleasure in ‘Just Kids’ was Smith’s decision to write generously and graciously about those who had betrayed, hurt or injured her deeply. This included Mapplethorpe, with whom she formed her first, unforgettable intimate relationship. Mapplethorpe’s exploration of his sexuality was complex. Maintaining an intimate relationship with Smith, he wasn’t always honest with her about other lovers. ‘Just Kids’ conclusion voices the impact of Mapplethorpe’s death on Smith–he died of AIDS in 1996. I’m not ashamed to admit that I cried. ‘Just Kids’ is one of those books that I carried around the house with me for a couple of days, reading while I ate, ignoring my kids, the mundane world suspended for the duration of the narrative. Although Smith didn’t have a Catholic upbringing, her explanation of Mapplethorpe’s struggle with the religion he’d been born into and his sexual identity, as seen in his self-portrait as the devil incarnate, filled in the gap I’d felt when I’d first encountered the image.

Finishing Smith’s book, I revisited Mapplethorpe’s photographs of perfect bodies on Google images and experienced a kind of melancholy. So many of Mapplethorpe’s models exhibit a sort of fascist beauty, the symmetry of form admired by the collector, the objectifying aesthete who searches out and then hoards an exquisitely formed object. Mapplethorpe’s interest in the mechanistic human body, its lust-inducing powers, its strength and harmony of form, its awe-inspiring curves and flexion, can no longer be viewed by me without an awareness of the extraordinary vulnerabilities of our bodied selves. Their unpredictable messages and preoccupations, as if the skin and what lies beneath has its own set of intelligences, its own systems of appraisal. As if it cannot help itself.

My friend, living out his anthropology theory, gave monogamy a go but failed. In his suffering, he nurses hope. My pain’s different. I’m writing a dissertation, which I find alternately absorbing, frustrating and stressful. Before I begin each day, I go to the gym, and subject my body to an intense workout. I can’t help but go hard, unable to stop until I feel an exhilarating endorphin surge. This activity, which I’ve discovered late, is playing out as an intense thrill. It’s almost like an illicit relationship. It’s reconnected me with a body that for so long has felt like little more than hands that cook and tidy, legs that climb stairs, a back that aches at bedtime. A vitality borne out of effort and sacrifice. Sexuality used to be such a dominant force, such a huge part of my identity; looking back at Mapplethorpe’s beautiful nudes I feel a pain that nearly makes me wince.