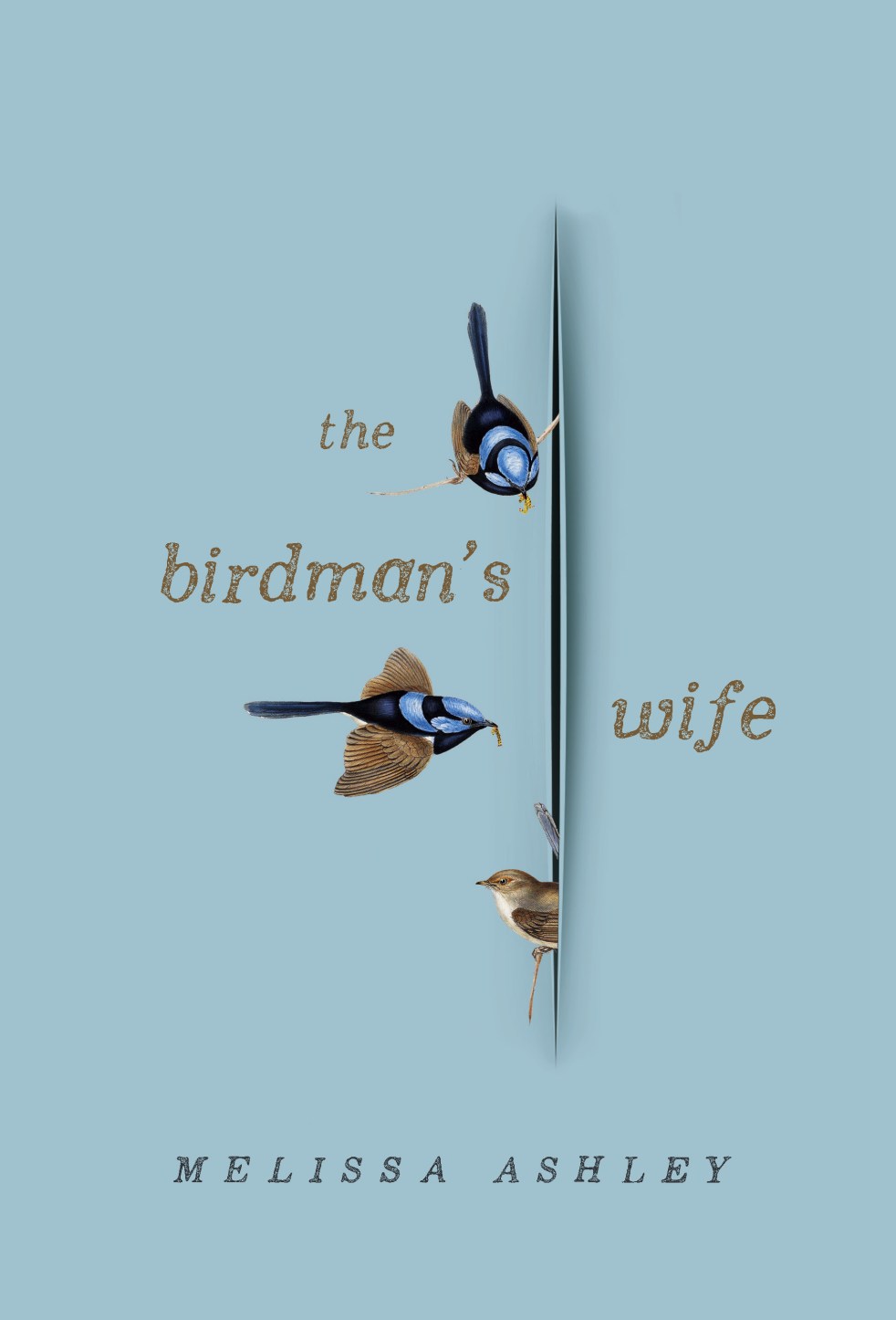

The Birdman’s Wife by Melissa Ashley

Affirm Press, 2016

‘The Birdman’s Wife’ is the timely resurrection to prominence of Elizabeth Gould, a fine artist and wife of John Gould, a noted Ornithologist in Regency England. The book tells Elizabeth’s story through courtship, marriage and motherhood, focusing on her work as an artist. As a work of ‘historical fiction,’ the time and multiple settings are so well researched and depicted that they come alive, including the figures of Edward Lear, Charles Darwin and Sir John and Lady Franklin. The Regency world in all its contradiction and change is seen in the lives and rise of the Goulds and their family.

Elizabeth Gould: a modern woman?

It was a clever strategy of Ashley’s to imagine her heroine, Elizabeth Gould, in a modern way, as a woman much like today’s professional mother who had to do it all. Elizabeth is a worker, mother, provider, lover – all pre-modern obstetrics, telephone, and even ocean liner. This depiction encourages readers to identify with Elizabeth, despite the large historical gap and her added assistance of servants, governess and cooks (and even mother and relation to look after assorted children while the Gould’ voyaged to Australia). This stance also allows Elizabeth to voice other ideas narratively, in keeping with modern views regarding the abundant specimens captured during her husband’s expeditions.

It allows Ashley to offer criticism of the practice through the character and also to have Elizabeth liberate some prized captives. To this reader there were parallels between the treatment of the native animals in Australia and that of the Aboriginals. That they were all treated as specimens to be used as the English saw fit, without any qualms of conscience. The unnecessary deaths of Australian animals, captured for the return voyage to England, was particularly hard to bare and written so deftly as to ride that fine balance between the ‘enlightened’ of the modern reader and outdated, immoral 19th century modes of behaviour. The character of Elizabeth at least, shows remorse for such savage waste.

Loss, family and sea travel

Ashley handled the loss of Elizabeth’s early children with great sympathy, compassion and depth, which helped bring the character to life and importantly again differentiate her from the relentless desire to ‘collect’ and ‘possess,’ as seen in her husband.

The voyage to Australia and the rendering of convict era Tasmania was well done and the difficulty for families being separated by hemispheres pre reliable communication added to the layering of the character of Elizabeth. The novel presented five Elizabeth’s: mother, wife, artist, sister and friend, and each role allowed Ashley to further develop and round out her heroine. The interactions between Elizabeth and her brother in Australia were made more moving, knowing she would probably never see him again after she returned to England.

Ashley has a great knowledge regarding birds and taxonomy and this depth and experience comes through on every page, especially the sections when dissections are occurring in the UK, on the voyages, and in Australia. The respect Ashley has for Elizabeth and her life and challenges is also evident and richly shown throughout.

Collecting: a construct of time, place and ideology

Fortuitously, I read the book while on holidays in Tasmania, where it was partly set. As an aside, while in Launceston, I saw ‘The Art of Science – Nicholas Baudin’s Voyagers 1800-1804’ an art exhibition of French explorers of Australia and their artworks from their voyages. I attended a lecture and was interested to learn that the French didn’t kill and return stuffed specimens for benefactors as the English (Gould et al) did, they drew and painted them only. Interestingly of course, they also only visited Australia, never ‘claiming’ it as their colony. The French expeditions predated the Gould’s.

One of the biggest insights for me from the novel was the act of collecting itself and what was entailed in the Gould expeditions. The detail Ashley provided of the sheer number of specimens killed shocked me. I think I’d always assumed they were all more like the French explorers, who drew from nature, rather than killing and preserving to take back trophies for museums or individual rich collectors.

Art and research creating layered characterisation

Scenes are cleverly written, offering layers of characterisation for multiple characters simultaneously. For example, the portrait painting scenes where the reader learns perhaps more about John Gould and his insecurities, cunning and political maneuvers, than they do of Elizabeth.

It’s hard to choose, but my favourite scenes were those depicting Elizabeth lost in her art, in the sheer ecstasy of creating and seeing something appear and fuse together on her blank page, born from her sheer talent and vision. The near possession Elizabeth experiences while creating the Resplendent Quetzal causes a very moving communion with her deceased children.

Reading the author’s note I was filled afresh with admiration at Ashley’s achievements in rendering Elizabeth Gould, having only eight pages of her diary remaining to act as a decoder for her thoughts and voice. Everything else was gleaned from years of research and study in Australia and America towards Ashley’s PhD. That layering of information and detail is rendered with dexterity.

Book Production Values: Congrats Affirm!

I can’t complete the review without reference to the production values of the book. I’m sure there’s many an Australian author and publisher in awe of this thing of wonder: a hard cover first novel. The beautiful Wedgwood or Robin’s Egg blue with its reproduction of Elizabeth Gould’s nested Fairy-Wrens feeding around a ‘tear’ invite or lure the reader further. Inside there are many illustrations featured in the book, including the pivotal Resplendent Quetzal.

This is an important work of redress allowing a woman of note to step out into the light again from where she had been hidden and neglected behind the plumage of her husband. Thank you Melissa Ashley for letting Elizabeth Gould ruffle some feathers again. I look forward to Melissa’s next book.

For more go to:

http://www.sarahridout.com.au/blog/2017/2/14/i6b3j0x8wst07xktdf68vafiaon8z1