http://www.betterreading.com.au/news/book-of-the-week-the-birdmans-wife-by-melissa-ashley/

Author: Melissa Ashley

Compulsive Reader: Review of The Birdman’s Wife by Sue Bond

I drifted towards the back of the workshop, my attention caught by a menagerie of shorebirds – a godwit, several sandpipers, curlews, dotterels, herons and varities of plover. For a heart-stopping moment the display tricked my eyes. It seemed the birds had flown into the room via a secret passage and, like children, settled before the warmth of the flames in the hope of being treated to a story. But as I drew closer I could see that the birds were perched on wooden boards, each miming its own dramatic scene. The sandpiper probed for molluscs. One of the plovers preened his shoulder. The heron reared to strike. The curlew held a shell in the barber’s tongs of its beak. The darter had drawn his long neck into a loop. (4)

This passage, early in this first novel by Melissa Ashley, displays Elizabeth Coxen’s keen imagination, sensitivity, and observational skills. The reader quickly realises she is a singular figure, a woman of warmth, sympathy, artistic ambition, intelligence. Coxen goes on to become the previously little known wife of John Gould, the famous English ‘birdman’ and naturalist of the nineteenth century. Ashley, a published poet and scholar in creative writing, has given us a picture of what she imagines Elizabeth to be as a human being and a skilled and dedicated artist, and it is a magnificent achievement.

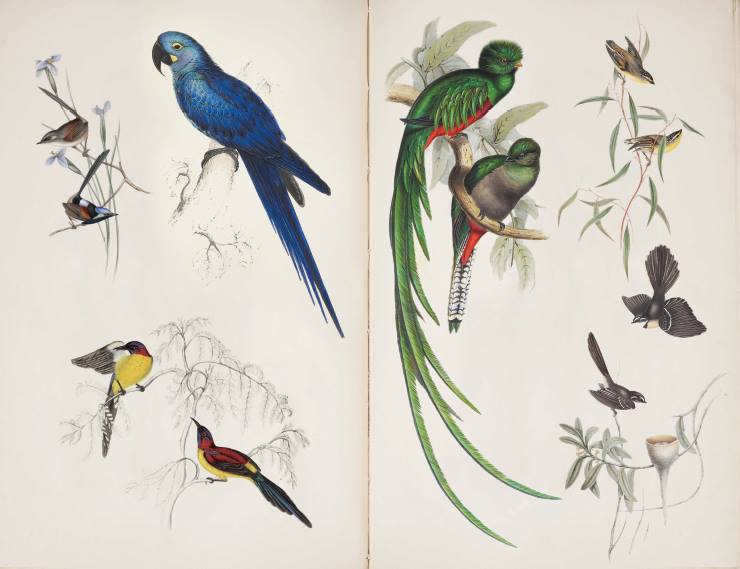

The author has researched her material thoroughly, even becoming a volunteer at the Queensland Museum and learning how to prepare ornithological specimens. This makes her descriptions of the preparations of the birds in her novel thoroughly convincing, as when Elizabeth is required to prepare the body of a brush turkey for its skeleton to be displayed. And the descriptions of her drawing and painting the prepared birds sometimes take the breath away, as with the quetzal, who ‘sported iridescent sheens in its plumage, like silk from China, gossamer and spider’s webs, droplets of water catching the light’ (94). The details of how the work was done, and the ingredients used, remind the reader of how difficult it was: ‘… my powders spilled across the table and I poured in the wrong amounts of water. …. For the yellow I used an Indian pigment made by feeding Brahmin cows the leaves of mango trees, then intensifying the colour of the animal’s urine by adding chemicals’ (96). The hours of work strained her eyesight, made her body ache; her husband drove himself from dawn to dusk as well, but she notes that he sometimes forgot that others did not have his stamina. These personal aspects of her characters are well described throughout.

The author explains at the back of her book why she became fascinated by the subject, which began with a poet and his poem about a particular bird, that eventually grew into an interest in Elizabeth Gould through being loaned Isabella Tree’s biography The Birdman: The Extraordinary Story of the Victorian Ornithologist John Gould (1991). Here she learned how important Elizabeth was to Gould’s ambitious goals: she ‘designed and completed some 650 hand-coloured lithographs of the world’s most beautiful bird species’ (378) while also raising a large family, and travelling to Australia for two years to work with her husband on compiling specimens and illustrating them for The Birds of Australia, that extraordinary multi-volumed work of scientific and artistic excellence. But her name and her work were not fully recognised, the lithographs usually being co-signed with her husband, and his name was more prominent generally. He apparently exploited Edward Lear, erasing his name from plates he reproduced for his publications, according to Peter Levi in his Edward Lear: A Biography (1995). But Ashley does not overplay this, preferring to imply the less attractive aspects of Gould’s character and practice through neat and gentle exchanges of dialogue, or the more robust scene towards the end of the novel, when Gould disapproves of the portrait of his wife executed by Richard Orleigh (an invented character as the real portraitist was unknown). It is implied he fears social approbation for allowing his wife to appear in a more active, less feminine role, of earning a living by art, something that might also affront his idea of himself as the provider for the household. This is skilfully accomplished, and shows the reader Elizabeth’s frustration and disappointment with her husband’s attitude, but also her resolution to deal with it by affirmation of her vocation: ‘In my heart, I knew I was an artist, no matter the appearances my husband needed to keep up to meet social conventions’ (327).

The novel follows the life of the couple from 1828, from the moment they meet in their early twenties. Edward Lear features as a much loved drawing companion and friend to Elizabeth, as well as a revered artist, and Charles Darwin praises her work, using a number of her lithographs for his book on the Beagle expedition. We follow them through the major episodes of their life together, including that perilous and demanding trip to and within Australia, but also see the private life through the eyes of Elizabeth. The descriptions of them eating cakes during their courting, the passages showing Elizabeth’s grief at the loss of loved ones, the sheer terror of a storm at sea, the friendship between Elizabeth and Lady Franklin, engender feelings of delight, sorrow, pathos, horror. Ashley knows how to tell a story, develop characters, write involving and natural-sounding dialogue, describe the unusual and the everyday alike.

A feature I noticed was the inclusion, every now and then, of Elizabeth’s reservations about the numbers of birds (and other animals) killed by her husband and his assistants in order to preserve and examine and record them. Another character may remind her that it is for science, and she agrees, but the uneasiness remains. And it passes on to her daughter Lizzie who expresses disapproval at the dead birds arriving at their home after the two year long adventure in Australia. I do not know if the actual Elizabeth Gould expressed these concerns, but it is entirely compatible with her character in this novel that she would. And an interesting reminder, or stretch out to the present times, of our impact on the world and its creatures.

The other novel that I kept thinking of in relation to this one is Mrs Cook: The Real and Imagined Life of the Captain’s Wife (2003) by Marele Day, but of course there are many fictional works written around real figures in history, such as Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell series, and Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang (2000). Some are more fictionalised than others, but Ashley has chosen to maintain the facts as they are known and to give the reader a possible, plausible, and beautifully crafted intimate portrait of Elizabeth Gould, and her vital part in the production of the books under her husband’s name.

Not only is this book fine fiction, but it is a thing of beauty as an object. It will beckon the reader from the shelves with its pale blue cover featuring fairy wrens, and the surprises when the book is opened and dustcover removed. A fitting production for an outstanding first novel.

http://www.compulsivereader.com/2016/11/05/a-review-of-the-birdmans-wife-by-melissa-ashley/

About the reviewer: Sue Bond is a writer and reviewer living in Brisbane.

Review: The Birdman’s Wife by Melissa Ashley and The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church by Dorothy Johnston

http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/review-the-birdmans-wife-by-melissa-ashley-and-the-atomic-weight-of-love-by-elizabeth-j-church-20161103-gshg3x.html

The first point I noted about The Birdman’s Wife is that Elizabeth Gould, not her husband John, the famous ornithologist, painted the pictures of birds I knew and loved as a child. While Elizabeth was credited by her initials, alongside John’s, for creating over 650 hand-coloured lithographs for a number of publications, including The Birds of Australia, very little is known about the artist; she was overshadowed by her larger-than-life husband. Melissa Ashley’s task, as she says in an author’s note, is to bring to life, through fiction, what the factual accounts have overlooked.

The first point I noted about The Birdman’s Wife is that Elizabeth Gould, not her husband John, the famous ornithologist, painted the pictures of birds I knew and loved as a child. While Elizabeth was credited by her initials, alongside John’s, for creating over 650 hand-coloured lithographs for a number of publications, including The Birds of Australia, very little is known about the artist; she was overshadowed by her larger-than-life husband. Melissa Ashley’s task, as she says in an author’s note, is to bring to life, through fiction, what the factual accounts have overlooked.

The Birdman’s Wife is written in the first person and Elizabeth’s interior life is well, at times poignantly, expressed. Readers first meet her in 1828, at the Zoological Society in London, where John Gould has rented rooms and Elizabeth’s brother, Charles, is working for him as a stuffer. Elizabeth and John, who has invited her to sketch from his collection, immediately strike a rapport. Meeting in the workshop is significant because the narrative is full of descriptions of killing, dismembering, stuffing and displaying birds and other animals. Elizabeth mainly draws from dead ones, though the times when she does manage to sketch from life are a joy to her. Not only killing, but capturing and attempting to keep wild creatures as pets – almost all of them die – is related as a common and unquestioned practice. Though Elizabeth shows more compassion than most, these scenes reveal her as a woman of her times. Her marriage to John, however, is depicted as a genuine partnership and collaboration.

All the female characters in The Birdman’s Wife are delicately and sensitively drawn, from Elizabeth’s mother to Daisy, her first maid after she is married, to Lady Franklin, wife of the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, who befriends Elizabeth, recognising a kindred spirit, after the Goulds arrive at Hobarton. At the end of Elizabeth’s life – she died aged 37, of puerperal fever after the birth of her eighth child – she comes to realise what being an artist has meant to her, in lyrical passages that combine her love of nature and keen observance of bird life with the special place she has created for herself. “I painted and I studied and, in this constant striving, became me.”

Elizabeth’s curiosity about the natural world links her, across more than a century, to Meridian Wallace, the main female character in The Atomic Weight of Love, who goes bird-watching on her own and is not the slightest bit interested in playing with dolls. Meridian is a brilliant student who falls in love with a physics lecturer 20 years her senior, marries and then follows him to Los Alamos, postponing, then finally abandoning her graduate studies in ornithology. In the middle decades of the 20th century, Meridian is not forced to endure successive pregnancies – she never has children of her own – but she submits to the husband with whose intellect she first fell in love.

Elizabeth’s curiosity about the natural world links her, across more than a century, to Meridian Wallace, the main female character in The Atomic Weight of Love, who goes bird-watching on her own and is not the slightest bit interested in playing with dolls. Meridian is a brilliant student who falls in love with a physics lecturer 20 years her senior, marries and then follows him to Los Alamos, postponing, then finally abandoning her graduate studies in ornithology. In the middle decades of the 20th century, Meridian is not forced to endure successive pregnancies – she never has children of her own – but she submits to the husband with whose intellect she first fell in love.

During decades of frustration and regret, Meridian does not abandon scientific study, but faithfully observes and records an extended family of crows. Her description of a crow funeral is particularly moving. Both authors are skilled at depicting their protagonists as many-layered, complex women, whose thirst for knowledge, and for the creative expression of that knowledge, survive against overwhelming odds.

John Gould is sufficiently present in Ashley’s novel, a believable mixture of qualities, beside whom Alden Whetstone in Elizabeth J. Church’s novel seems an enigmatic character. Whetstone is invited to work on the Manhattan Project, then stays on at Los Alamos after the war. Of necessity, his work is secret, but his change from the scientist who delighted in teaching and sharing his ideas, to a grumpy, punitive husband, is harder to fathom.

Meridian finally finds fulfilment in helping young women realise their potential. The Atomic Weight of Love spans tumultuous decades – Hiroshima, the Vietnam War, the women’s movement – but the author glosses over the many changes these events brought to people’s lives, not only those people who were involved in them directly.

Both novels contain many fine descriptions of the natural world, and are beautifully produced. The Birdman’s Wife is a delight to handle, a hardback with the endpapers displaying some of Elizabeth Gould’s finest work.

Dorothy Johnston’s latest novel is Through a Camel’s Eye.

Talking Elizabeth Gould with Louise Maher on Afternoons, ABC 666

While most people were placing bets for the Melbourne Cup, I had great fun this afternoon talking about The Birdman’s Wife and the incredible life and artistry of Elizabeth Gould. Click on the link below to listen to the podcast. Thanks ABC 666 and Louise Maher and her great team.

Audiobooks return the pleasures of reading to the print and visually impaired

Not long after I sold the rights for The Birdman’s Wife to Affirm Press, I was delighted to be offered a publishing contract from Wavesound, a new audiobook imprint dedicated to making Australian titles available in alternative formats to print. Wavesound is an imprint of Audible, the world’s largest publisher of audiobooks. All of Wavesound’s audiobooks are recorded locally in Sydney, and employ Australian actors.

Not long after I sold the rights for The Birdman’s Wife to Affirm Press, I was delighted to be offered a publishing contract from Wavesound, a new audiobook imprint dedicated to making Australian titles available in alternative formats to print. Wavesound is an imprint of Audible, the world’s largest publisher of audiobooks. All of Wavesound’s audiobooks are recorded locally in Sydney, and employ Australian actors.

While readers may be aware of audiobooks as a new form of media by which to enjoy reading, few realise that for the print-impaired, audiobooks are the only means of accessing our culturally significant local and national stories.

At the age of 10, my 12 year old daughter was diagnosed with cone-rod dystrophy, a degenerative retinal condition that affects both her central and peripheral vision. Diseases of central vision, known as macular dystrophies in children, and macular degeneration in adults, make reading particularly difficult, as the fine focus needed to engage with print is severely degraded. For some, larger print titles are the answer, but for many, with significant central vision damage like my daughter, the only way to access written texts is via an audio channel. (If she does try to read very large text, it is by scanning words with her peripheral vision. This causes headaches and dizziness, which as you can imagine, destroys all pleasure of losing oneself in the imaginary world of a book.)

Unfortunately, there is a world-wide poverty in accessing audio books for the visually impaired. Indeed, only 5% of texts make it into audio formats. For my daughter, this means that contemporary literature by Australian authors suitable for her age group is often not available. For example, she cannot always access class texts in a suitable format, and instead has them read out to her by classmates or her teacher. My daughter is and always has been an avid reader. She is currently making her way through Anne of Green Gables. She has read Harry Potter several times over and is keen to begin The Lord of the Rings, but there many recently published titles that her friends enjoy that she simply cannot access. And this is why an imprint like Wavesound’s commitment to publishing unique Australian stories in audio formats is so important.

The audiobook of The Birdman’s Wife was published in the same week that the printed text was released. With Wavesound and other imprints, there is no lag – determined by market popularity, for instance – in accessing an audio title. For the print-impaired reader, this means that having the same diverse choices as any other reader to engage with culturally relevant local and national stories is made possible.

Another bonus to able and impaired readers is that while you can purchase your own copy of an audiobook to listen to at your leisure, you can also access audiobooks on a downloadable format from your council library – far more convenient than popping into the physical version to borrow the printed title.

I am filled with gratitude that Wavesound has taken the step of making The Birdman’s Wife into an audiobook. Natasha Beaumont’s beautiful narration gives a very different reading experience, rich, lush and nuanced, which can be enjoyed by all readers, not just the print-able. Although my daughter is a little young to connect with The Birdman’s Wife, I look forward to the day when she tells me that she is ready to read the novel I dedicated to her.

To hear a sample of Natasha Beaumont’s gorgeous narration of The Birdman’s Wife, follow the link below (it will take you to the audible website). Enjoy!

http://www.audible.com.au/pd/Fiction/The-Birdmans-Wife-Audiobook/B01M1SETYE

Book Review – ‘The Birdman’s Wife’

Title: The Birdman’s Wife

Title: The Birdman’s Wife

Author: Melissa Ashley

Genre: Fiction (historical)

Release Date: 1st October, 2016

Rating: ★★★★★

“Artist Elizabeth Gould spent her life capturing the sublime beauty of birds the world had never seen before. But her legacy was eclipsed by the fame of her husband, John Gould. The Birdman’s Wife at last gives voice to a passionate and adventurous spirit who was so much more than the woman behind the man.

Elizabeth was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover, helpmate, and mother to an ever-growing brood of children. In a golden age of discovery, her artistry breathed wondrous life into countless exotic new species, including Charles Darwin’s Galapagos finches.

In The Birdman’s Wife a naïve young girl who falls in love with an ambitious genius comes into her own as a woman, an artist and a bold adventurer who defies convention by embarking on a trailblazing expedition to the colonies to discover Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.”(Simon & Schuster)

So I need to first get out of the way my gushing over the cover. While I’m happy to have read this book, my one regret is that I read it in digital format; as soon as next payday rolls around I’ll be taking myself off to get a hardcopy of it. There are some of Elizabeth Gould’s illustrations in the book and after seeing photos of it on Twitter, I really feel like I missed out. So if you’re going to read this, you must get your hands on a physical copy.

The inside of the book was just as lovely as the outside. Melissa Ashley’s writing is beautiful and really evoked a sense of time and place both in London and in Australia, the latter in particular:

“I recall the Australian eucalypts stretching their coppery limbs towards the sun, the cedars boasting girths the width of a coach. I remember the parrots of that great continent, painted every hue of the rainbow, whole clouds squawking past, and a sky so huge you could see it curve at the edges.”

The narrative felt natural and not at all forced, and it made it easy for me to settle in and block the world out for a little while. This was an especially big thing for me, as the narrative is from a first person perspective which I sometimes find difficult to read, mostly because the voice doesn’t always seem real. But this was never an issue when reading The Birdman’s Wife.

I found the life of Elizabeth Gould completely fascinating and she truly was an admirable woman. She was an artist, wife, mother, and convention breaker in a time when her expected place was in the home. Although this is a fictionalised account, it doesn’t change the fact that it’s a real shame that Elizabeth is less well-known than her husband. While it was quite fortunate that she married a man who recognised that she had talent and he enabled her to put that talent to use, the reality was that they were a team and without her artwork and dedication he may not have been successful as he was.

The book gets quite detailed in relation to the collection and taxidermy of the birds, which I personally found interesting, but it may not be everyone’s cup of tea. I actually thought it provided a great contrast between Elizabeth and John: she taking the less destructive route of recording the birds through art (that being said, her drawings were largely based on specimens collected by John); while he was the embodiment of the typical Georgian/Victorian attitude towards conservation, i.e., they hadn’t given it a lot of thought at that point – at least not to the extent that we think about it today. That’s not to say that he killed needlessly, but he certainly had more of a focus on collecting than observing.

I had a great time reading this book. Not only was it a pleasure to read, but it catered to my love of nature and my growing interest in natural history. The Birdman’s Wife is probably the worst nightmare for the little birds I share my home with, but I really enjoyed learning about taxidermy practices, as well as Elizabeth’s own methods for painting (particularly the mixing of colours). It’s also worth reading the author’s note at the end, as Ashley tells the story of how her book came about and the things she did as part of her research, including spending some time as a trainee taxidermist to learn all the ins and outs of the occupation. It really was just as interesting as the book itself.

Many thanks to Simon & Schuster and NetGalley for providing me with a review copy.

Taking Five with Melissa Ashley

Melissa Ashley’s meticulous attention to detail is on show in her first novel, The Birdman’s Wife, which explores the life and relationships of artist Elizabeth Gould. AWM intern TJ Wilkshire spent some time with Melissa to discuss birds, art, poetry, and secret women’s history.

Your debut novel tells the story of Elizabeth Gould, wife of John Gould, the famous ornithologist. Can you tell us what inspired you and how that spark of inspiration drove you to write an entire novel?

It was a bit of a long and convoluted path, with a number of interests that pulled together, until the point of writing Elizabeth’s story became almost inevitable. Elizabeth and John Gould’s intense creative relationship intrigued me from the very beginning, not least because it reflected a similar relationship in my own life as a writer. My love of birds was first inspired by my love for a poet, and his poem about a black-faced cuckoo shrike. An aspiring writer myself, I had never heard of this common bird, and its enigmatic presence in the poem sparked in me a desire to learn all about the birds that sang and preened in my Brisbane backyard. Curiosity is a powerful motivator and, during the next decade and a half, my interest in Australia’s birds steadily increased until I began birdwatching in earnest.

Tied to my hobby was a fascination for antique etchings and prints of birds; I loved the illustrations’ awkward grace. In 2004, the discovery of a cache of 56 paintings of Australian birds and plants by George Raper, a midshipman and navigator on the First Fleet, seized my imagination. The watercolour paintings were uncovered in England during an inventory of the estate of Lord Moreton, the Earl of Ducie. Intrigued by the illustration of a laughing kookaburra, one of the evaluators brought the buried collection to light. Once part of Sir Joseph Banks’ First Fleet materials, the collection had passed into the Ducie family and lain untouched for two hundred years. This was a truly astounding find. Although Raper’s paintings were naïve, his attention to the details and colours of the birds’ wings and feathers was extraordinary. By this time my birdwatching had intensified into a near obsession, and I began to travel great distances to encounter new species, which I would excitedly add to my ‘life list’, a record of birds seen for the very first time. My fellow poet, now a birdwatcher too, and I drove to Queensland’s far western mulga region, explored the Mallee in South Australia, endured the rough currents of the Southern Ocean, peering through binoculars and camera lenses to chase the intense experience of sighting a new species. The excitement of this pursuit led to me wonder what it might have felt like for George Raper and his fellow First Fleet bird enthusiasts’ when they encountered Australia’s unique birds, so utterly different to the species of Britain and Europe, for the first time.

The appeal of delving into Elizabeth Gould’s forgotten history, for me, was intimately connected to the thrill of twitching never-before-seen birds, although it had a rather more prosaic beginning. One summer afternoon, my birding partner rescued an Indian ringneck parrot perched on the net of a tennis court. He phoned, full of excitement, asking me to find a book about caring for parrots and to buy a cage to house it. A friend loaned me a book about caring for parrots, along with a biography of John Gould by Isabella Tree. In Tree’s fascinating biography, I discovered Elizabeth Gould, who played a fundamental role in the creation of John Gould’s publishing empire.

In her decade-long career, Elizabeth designed and completed some 650 hand-coloured lithographs of the world’s most beautiful bird species. Her ability to manage a demanding artistic career capturing the sublime beauty of hundreds of exotic birds for her husband’s celebrated collections, including illustrating Charles Darwin’s Galapagos finches; to care for an ever-growing brood of children; and defy convention to join John on a two-year expedition to the Australian colonies, intrigued me enough to take up the thread of her thinly sketched character and follow wherever it led. I thought that readers might find her story as interesting as I did, and enrolled in a creative writing PhD in order to be given the financial support, time and guidance by the expert staff at the University of Queensland’s School of Communication and Arts, to hone and develop the project.

Can you tell us a little bit about your writing processes? How did you move from writing poetry to writing a full novel? Was it harder than you expected? Previously to this novel you wrote poetry. Has poetry informed the kind of language you have written in your novel?

My writing process is very slow. I hope it speeds up in my next novel, a work of historical fiction also. I would say getting started with the real narrative, the fictional voice, of Elizabeth Gould, as opposed to cataloguing and presenting the material in a more biographical way, was the most challenging aspect of writing the novel. I was very concerned about being faithful to the historical and archival record of Elizabeth’s life. I over-compensated, in a way, with my fear that I would not seem authentic in my knowledge about Australian birds, the places I set the novel in, the time and environment, the cultural setting. I’m a researcher by training and there is nothing more that I love than digging into files and archives. For Elizabeth’s story that meant 1830s London and Australia; ornithology, zoological illustration, voyages, childbearing and rearing practices. I’d outlined the plot but there comes a point when a writer begins to feel an itch to start the first scene of the first chapter. I came to a stage where I felt that I had spent enough time with printed books. I felt that I needed to get out into the field, to go birdwatching, to learn bird-stuffing, to handle archival materials that Elizabeth Gould made herself. These more tactile and adventurous experiences really helped me to make that jump from the biographical Elizabeth, to imagining her emotional journey, her personal experiences and challenges, as the narrator of The Birdman’s Wife.

Just to add to that, I’m a fiction writer, not a scientist or historian, so these evocative ‘field’ experiences really helped to unlock my imagination.

When you were writing about Elizabeth Gould, did you start to form a relationship with her? Did you get to know her like a friend during your research of her? When the novel was finally finished, how did you then separate yourself from Elizabeth to then begin the editing process?

I think I did. It might sound a little cliché, but, particularly towards the end of the book, I felt very sad about her early death. My publisher, on numerous occasions, accidentally calls me ‘Elizabeth’, which always makes me smile. I love writing about artists, it doesn’t matter what form of art, but visual art and writing has a particular appeal, and women’s hidden stories. I am also a mother, trying to juggle everyday life with kids, and keep my imagination flowing, trying to find time to write, so that was a big draw for me, in identifying with Elizabeth, who had eight children. (I only have two, and that is challenge enough!)

How did you build a novel around Elizabeth’s life? Were there certain points in her life you wanted to focus on more than others?

How did you build a novel around Elizabeth’s life? Were there certain points in her life you wanted to focus on more than others?

That’s a very pertinent question. I was really concerned about being faithful to the historical facts, the historical record of Elizabeth’s life. That said, I did not always agree with the biographical interpretation of the sort of person she was. She was often, or always, presented as John Gould’s subordinate, whether it was as his obedient and supportive wife, or as a mere ‘assistant’ to his publishing house and ornithological pursuits. The real situation was somewhat different. John and Elizabeth Gould had very separate talents and skills, and yet they came together in the wonderful hand-coloured folios they produced together. I like to think that they were more, as a couple of creatives and scientists, than they were individually. John Gould would never had embarked upon his ambitious project to illustrate the world’s most exotic and interesting birds without Elizabeth’s drawing and painting skills. He was a hopeless sketcher. So, he has a lot to thank her for.

I wanted to portray the interior, emotional aspects of Elizabeth’s life. So it was a matter of interpreting certain events and circumstances, for instance, leaving her three young children behind in order to travel to Australia to make artworks of our lovely birds, how courageous she was in doing this, but also, what a sacrifice it was for her. She really missed her children. And then there is the poignant or horrible irony even, of her unexpected death, a year and a day after her return to England to work on The Birds of Australia.

I also really wanted to focus on her development as an artist. How she grew from making almost awkward images – very meticulous but also rather stiff in composition – of birds in her first folio, A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains, to become a fully-fledged artist, who produced iconic and extraordinary paintings and lithographs of the world’s most beautiful birds, including many wonderful images of Australia’s unique species. As science evolves, with DNA testing and research, more and more is learned about the Australian continent’s place in the evolution of the class of birds as a whole. Indeed, some of our birds exhibit behaviours, such as co-operative breeding, that are very ancient, and connected to our harsh, arid environment.

Were there any scenes of particular parts of the book that were challenging to write for any reason?

Getting started was the most difficult part of the novel. It was drafted about five times, and as it was revised for publication, what to include in the set-up of Elizabeth’s story involved much thought and experimentation. That said, the last third of the novel was relatively easy and fun to write. Once I reached a certain point, I followed where Elizabeth’s led me. In order to do this, I had to go to Hobart, where she stayed for nine months, to envision and become confident about that place to write about it with conviction. That research trip, about 18 months into the project, shifted a sort of hump, where the narrative took over the attention to biographical detail.

You can read more about Melissa Ashley and The Birdman’s Wife here.

TJ Wilkshire is a twenty-something Brisbane based artist and writer. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Writing and English Literature and is currently studying the WEP Masters at the University of Queensland. Her work focuses on birds and she hopes to one-day turn into one. Wilkshire’s poetry has been published in Peril and Uneven Floor, and won the NotJack Competition.

The Birdman’s Wife by Melissa Ashley: Elizabeth Gould’s forgotten talent

Caroline Baum

Spectrum October 14, 2016

The birds came first. Melissa Ashley was a twitcher before she decided to write The Birdman’s Wife, a historical novel that brings Elizabeth Gould out of the shadow of her husband John, Australia’s most celebrated ornithologist.

A New Zealander, Ashley, 43, came to Australia aged eight with her parents as the eldest of four children. As an adult living in inner-city Brisbane, she worked in disability care, helping deaf people talk on the phone before technology took over that role. She first became interested in birds when her poet partner wrote a poem about a black-faced cuckoo shrike. Ashley had also published a collection of poems, A Hospital For Dolls, in 2003 and decided that in order to share her partner’s other enthusiasm, she would join a birdwatching group.

The Birds of Australia, Mitchell Library. Photo by Edwina Pickles

“I seemed to spend all my time focusing my binoculars,” she says of her amateur beginnings. But she caught the bug and was soon going out with more seasoned watchers to count waterfowl as part of a data-gathering project and spending holidays interstate to spot highly prized species, including going to Far North Queensland and paying a guide to find a golden bowerbird in its natural habitat. “I became obsessed with my bird list to the point of competing with my partner.” Even her four-year-old daughter shared her interest: “She made herself wings and ran around the house flapping her arms.”

After the poet flew the nest, Ashley remained a committed birder (her website is called Satin Bowerbird). Her favourite species are the fairy wren she sees frequently in her backyard, featured in an exquisite painting by Elizabeth Gould on the cover of her novel, and the royal albatross – a scene-stealing presence in an entirely imagined episode in the book, but which Ashley has yet to see for herself.

As a self-confessed research nerd Ashley is happiest fossicking about in archives and says she enjoyed writing the scenes on board the ship that brings the Goulds to Australia because she loved learning the nautical terminology.

“It was The Birdman, Isabella Tree’s biography of John Gould that drew me to Elizabeth,” she says. “She made her such an enigma. I wondered how it felt to be pregnant every nine months, to lose two children, to leave family behind to join her husband’s expedition to Australia, to develop her skill as an artist and become such an essential part of Gould’s fame and success while being so under-acknowledged.”

Elizabeth Gould designed and completed 650 superb hand-coloured lithographs of the world’s most beautiful bird species, including Charles Darwin’s Galapagos finches, before dying at the age of just 37. As well as being her husband’s secret weapon, she became close friends with Lady Jane Franklin, another woman remarkable for her curiosity and initiative in the Victorian era, as wife of the Governor of Tasmania. And she formed a professional friendship with the eccentric artist Edward Lear, who joined the Goulds for seven years due to his impecunious circumstances. “He was an ally to Elizabeth in that he teased John slightly about being a bit of a miser and very demanding.”

These secondary characters act as a foil to John Gould, who comes across as relentlessly energetic, ambitious and entrepreneurial. In real life, he was no match for his his wife’s artistic skill, despite his fame for the book Birds of Australia. Ashley says she too lacks drawing ability.

Not to be deterred, Ashley took up a dare from an unusual source, a volunteer taxidermy group member at the Queensland Museum. In order to fully appreciate Elizabeth Gould’s talents for making dead, stuffed specimens come alive on the page, Ashley learned the basics of the craft. “I needed to look at plumage, beaks, claws,” she says.

It was a fitting decision, given that Elizabeth’s brother Charles worked for John Gould as a taxidermist and introduced the couple. John Gould employed a team of so called-stuffers; Ashley joined the volunteers’ circle for a year. “It was terrible to start with, my fingers bled from the sewing. It’s quite a business, you get the specimens out of a giant freezer and use scalpels to cut them open to and remove the innards, including removing the meat out of the wings, which is very fiddly, and then you fill the body cavity with Dacron and cotton wool before stitching them up to be wrapped in gauze like a shroud.

“The best part was the stories the others told about the dangers involved in collecting fresh specimens of roadkill. One volunteer had almost fallen into the carcass of a rotting humpback whale. Another had given her med-student daughter a taxidermied rat she had dressed in a tiny coat and equipped with a doll-sized stethoscope. It was like a sewing circle although the smell was pretty terrible and made me retch.”

Fortunately, she was not faced with the task of stuffing an albatross. “The scene in which the albatross is captured is a turning point for Elizabeth as a character, when she questions the killing of all those birds and ultimately accepts it. But I could not let the albatross be killed; it felt taboo. And although Elizabeth made 10 plates of seabirds, she never did an albatross.”

Thanks to a serendipitous connection with a fellow volunteer, Ashley met a descendant of Elizabeth Gould’s nephew and was shown precious photographs of the homestead where Elizabeth stayed with her brother, who had come out to Australia as a pastoralist. These leads whetted her appetite for further scholarly research.

Writing the novel as part of a PhD at the University of Queensland meant Ashley was able to deepen her investigation and speculation over four years during which she wrote five drafts of the manuscript. It was as a member of a scholarly nature-themed reading group that she met fellow novelist Inga Simpson, who would become a mentor. “She took me under her wing,” says Ashley, seemingly unaware of the pun. She was also inspired by Elizabeth Gilbert’s novel The Signature of All Things, about a heroine of great scientific curiosity, which she read halfway through writing The Birdman’s Wife.

As part of her research Ashley was lucky to have access to unpublished memoirs by Elizabeth and John’s daughter, the marvellously named Eliza Muskett Moon, held in the world’s biggest Gould collection at the University of Kansas.

At Sydney’s Mitchell Library she was able to view the so-called “pattern plates” or templates that Elizabeth painted as a guide for the colourists her husband employed. After making a case to the special collections department, she was eventually given permission to look at the precious originals of Elizabeth’s diary, which were brought up from a natural-disaster-resistant safe.

“It was only eight pages and it was buried deep inside a cache of John Gould’s letters as if it had no significance in its own right. In fact it was indexed under his name,” says Ashley of the journal that Elizabeth wrote documenting her impressions of a two-week visit to Sydney, Newcastle and Maitland. As diary keeping was a popular occupation for a woman of her rank, one can only assume that Elizabeth wrote similar accounts of her travels to Tasmania, where she spent a year, and her time in the Upper Hunter Valley staying with her brother, but they have not survived. Only a dozen of her letters exist, while her husband’s correspondence runs to many thousands of letters.

Ashley’s achievement is even more impressive given that she is a single mother with two children, one of whom is losing her eyesight. “Thank goodness for audio books,” she says. Ashley has not written a poem for 13 years. “It’s as if I grew out of it,” she says, with a laugh that she quickly stifles as if to say such a thing were indecent.

She is already at work on her next novel, also a work of historical fiction, this time about a 17th-century aristocratic French woman who wrote fairytales pre-dating her well-known compatriot Charles Perrault and the Grimm Brothers.

“Once again I can immerse myself in research,” she says, acknowledging that “it may be a form of procrastination”. And again, she has chosen as her subject a woman written out of the history books. “That is my lifelong passion. I’ve tried writing contemporary fiction but I feel lost when it comes to writing about today. I seem to relate more to the past, but still want to address issues that are relevant today.”

The Birdman’s Wife is published by Affirm Press at $32.99.

And another thing: Ashley participated in a competitive “twitchathon” searching for 200 birds across Brisbane but was disqualified for getting a speeding ticket.

Launch, The Birdman’s Wife, Avid Reader, 13 October, 2016

Thank you to everyone who came along to the launch of The Birdman’s Wife at Avid Reader. It was a wonderful evening with much love in the room. I had the time of my life!

Thank you to everyone who came along to the launch of The Birdman’s Wife at Avid Reader. It was a wonderful evening with much love in the room. I had the time of my life!

I’ve posted the beautiful speech Inga Simpson wrote to launch The Birdman’s Wife into the world.

Launch speech for Melissa Ashley’s The Birdman’s Wife. 13 October 2016 Avid Reader by Inga Simpson

Melissa’s beautiful book, The Birdman’s Wife, has already had a quite a bit of attention around the place but as we all know, a book isn’t really launched until it’s launched at Avid Reader, among friends and family and your fellow Queensland writers. So thank you to Avid for having us and to all of you for coming along.

A lot of you here already know Melissa but for those who don’t, she has began her writing life as a poet, publishing a collection called The Hospital For Dolls, which was very well received. She has also published stories, essays and articles. But luckily for us, she has made the move to novelist, realising that we have more fun, lead happier lives, and earn more money. She recently completed her PhD in creative writing and teaches at UQ. The Birdman’s Wife was part of that PhD. It is her first novel. And what a beautiful novel it is.

I was was really chuffed when Melissa asked me to launch this book. Not just because I’m fond of birds but because I know this story. And I know what a journey it has been for Melissa: the research, the writing, and the book’s path to publication. I met Melissa at UQ. We were both doing PhDs, there was some common ground in our research, around natural history and environmentalism, and we had a supervisor in common, who thought we should talk. I’m really glad we did. As some of you know, doing a PhD is a major journey in itself, and part of the process – because it takes such a long time – seems to be the universe throwing you some major life events during your candidature just to see how much you can take. The upside is the conversation, camaraderie, support – the friendship of your fellow students. And I really admire Melissa’s strength in getting through her PhD journey, and am so pleased with this happy ending, that makes it all worthwhile, that this story, The Birdman’s Wife, has found its way out into the world.

So the story. A Birdman’s Wife is a fictional biography of Elizabeth Gould, the wife of the famous 19th Century ornithologist, John Gould. He was and still is known worldwide as ‘The Birdman’ and ‘The Father of Australian Ornithology,’ renowned for creating the most detailed and beautiful hand-coloured lithographs of birds the world had seen. But few people know that his wife, Elizabeth, was the principal artist. It was Elizabeth who created more than 600 of the hand-coloured plates published in Gould’s luxury bird folios.

Vanessa Page making me giggle.

Like many of the birds Elizabeth drew, the more colourful male got all the glory and attention. The Birdman’s Wife pulls her out of the workroom and onto the world’s page. She was a remarkable artist, and a remarkable woman, ahead of her time. Elizabeth defied the conventions of the day, leaving behind her three youngest children to join John on a two year expedition to Australia to collect, study and illustrate our unique bird species.

In many ways this is a familiar story, a woman in the shadow of her husband, juggling her art with her roles as mother, wife, business partner. It still resonates today. Finding the time and focus to write is still a struggle for many women, negotiated around other careers, and our roles as mothers, wives and partners. It’s still harder for us to believe in our work, in ourselves, and to put to ourselves in the spotlight.

Elizabeth Gould lived during a time when the world was obsessed with discovering and classifying the natural wonders of the new world. She was right at the centre of it, working with Edward Lear, John Gilbert, and Charles Darwin, who was so impressed by her art works that he invited her to illustrate his Galapagos finches.

Suzy, Tara and Lizzie, bookclub queens

I’m big on verbs, doing words, as effective description, and I couldn’t help but admire the way that so many of the verbs in this book relate to birds: winging, fluttering, flitting, flying, nesting, plucking. And in a book about a bird illustrator, that’s exactly as it should be.

Melissa’s research for this book has been meticulous and extraordinary – paralleling the work Elizabeth put into her illustrations. The historical and natural history contexts and details, particularly in relation to birds, taxidermy, and her drawing and printing processes. Melissa actually learned taxidermy herself, which I’m hoping she’ll tell us a bit about.There are plenty of gloriously gruesome details in relation to taxidermy in the book: removing slivers of flesh, stuffing stomachs, and stitching up the holes left by shotgun pellets.

Fiona and James of Avid Reader holding down the fort

Melissa is a bit of twitcher, a birdwatcher that is, and her live bird descriptions are the highlight of this book for me. Just beautiful and again, a fitting match for Elizabeth’s drawings. From green parrots tottering across the grass warbling to each other as they dig for seed, to the superb fairy wren with his feet curled on a branch “like a miniature coat-hanger’s hook.” Melissa describes the male fairy wrens making high-pitched trills, while the females make “quieter weaving whispers” in response. And that’s so true of fairy wrens – but I wonder if it isn’t perhaps also a metaphor, too, for women artists.

There’s another parallel, I think, in the timing of this book. A tapping into the Zeitgeist. Like in Elizabeth Gould’s day, the world is currently very interested in natural history. Not so much discovering new species, but trying to stop them slipping into extinction. Trying to reconnect with nature.

So, although set during the 1800s, The Birdman’s Wife speaks to us today. Melissa has brought to life a voice from the past, Elizabeth Gould’s voice. This book has, at its heart, a sense of wonder at the natural world and for the creative process – of passion and creativity that needs to be expressed – just as fiercely by women as men.

And on that note, I’d like to call Melissa into the spotlight, and declare The Birdman’s Wife officially launched!

Review: The Birdman’s Wife by Cass Moriarty

The Birdman’s Wife is the debut novel of Melissa Ashley, published by Affirm Press. It has arrived on the literary scene accompanied by a good deal of promotion and publicity – and for good reason. The Birdman’s Wife is a fascinating historical study, a meticulous and well-documented scientific report, an emotional story, and an engaging read.

The Birdman’s Wife is the debut novel of Melissa Ashley, published by Affirm Press. It has arrived on the literary scene accompanied by a good deal of promotion and publicity – and for good reason. The Birdman’s Wife is a fascinating historical study, a meticulous and well-documented scientific report, an emotional story, and an engaging read.

Elizabeth Gould was a wife and mother, an artist and illustrator, a tenacious, curious, dedicated and adventurous woman. She was the Birdman’s Wife, the Birdman of course being John Gould, the famous father of ornithology, who spent much of the second half of the 1800’s collecting, displaying, cataloguing and publishing wildlife, most particularly native birdlife from the wilds of Australia. John Gould’s life and intellectual pursuits are well-documented; there are countless books by him and about him that depict his scientific endeavours. Less known is the invaluable contribution that his wife Elizabeth gave to his projects. In fact, while she was alive it seems it really was more a case of ‘their’ projects, for evidence points to Elizabeth playing a vital role in the studies they conducted.

In this novel, Melissa Ashley has pored over countless primary and secondary sources, she has travelled near and far, she has rolled up her sleeves and got her hands dirty experiencing taxonomy, she has hunted down descendants and family history, all in order to shine a spotlight on the talents and achievements of Elizabeth Gould. She has spun fiction from the base threads of fact, and what has resulted is a compelling and intriguing insight into Elizabeth’s mind, her actions, her emotions, her family life and her work.

Any book such as this automatically has a spoiler alert: any cursory internet search will reveal that Elizabeth Gould died after bearing her eighth child, at the young age of only 37. And yet this fact does not detract from the intense suspension and pace of the novel; it does not dissuade the reader from frantically turning the pages in order to discover what happens next. And so very much did happen in her relatively short life, and because the novel is written in such an engaging and interesting style we are immediately drawn to the voice of Elizabeth as it rises from the pages from over 150 years earlier; from the very first chapter we care deeply about this woman and her dreams, we fall in love with her, we fret with her about her children, we worry over the quality of her work, we feel her fear and trepidation as she embarks on the epic voyage that will change her life.

Elizabeth meets John Gould by chance. They marry, and discover they have much in common, including a love for animal and birdlife, and a desire to share their knowledge of creatures with others – John through his words and Elizabeth through her drawings. John skins and stuffs specimens; his wife illustrates them, capturing their essence, their colours, their peculiar poses or habits or characteristics. Her magnificent illustrations breathe life into her husband’s lifeless specimens. Together they produce definitive manuals on Australia’s birdlife after a two-year period of study here, the pair travelling (five months by sea) with their eldest son, and leaving their other children in the care of Elizabeth’s mother. She produced over 650 hand-coloured lithographs; she was asked to paint Charles Darwin’s Galapagos Finches. Nearly all of these works were signed by both her husband and herself, as was common at the time, but it was Elizabeth’s talent that really brought the beauty and uniqueness of many species to light.

Access to Elizabeth’s diary and correspondence have allowed Melissa to imagine the details and minutiae of her daily life. Her love for her children – the terrible wrench of leaving them in order to accompany her husband on his travels to the southern continent! Her feminist thoughts, bound by her Victorian constraints. Her artistic ambition, overshadowed always by her husband’s drive and reputation.

This book will appeal to artists, to environmentalists, to bird-lovers, to scientists and to taxonomists. But it also has general appeal to readers, to lovers of a good story. The writing is well-researched, concise and captivating. The story is gripping and enthralling – even though we already know the facts and the ending! Melissa achieves this by making it about the journey, not about the destination. Each new child, every fresh illustration, all of the small, quiet personal achievements, and each major scientific discovery – all are celebrated and enjoyed with equal pleasure.

And as an additional bonus, the beautifully-bound hardback is complete with full-colour endpapers of Elizabeth’s renderings.

I was fortunate to hear Melissa speak at the Queensland Museum & Sciencentre about her research and her forays into the (smelly) world of taxonomy, about her tantalising glimpse of Elizabeth the woman and how she set about discovering the whole of her life story in technicolour. It is clear that Melissa harbours a great love and respect for the bird world, and for those who had the opportunity years ago to make startling discoveries and world-first observations. It is also clear that she has managed to unveil the story behind one of the great and intrepid female characters of history. Surely the phrase ‘behind every great man stands an even greater woman’ must have been coined about Elizabeth Gould. I have seldom found history to be so absorbing and so thrilling, and yet so familiar and so relevant.