Join Books Create Australia’s campaign to protect literary culture in Australia: our book industry, the livelihood of our authors and our unique Australian stories. Show your support today by signing Books Create Australia’s petition to The Hon. Scott Morrison, MP, to stop the parallel importation of books and save Australian literature.

https://www.facebook.com/pg/Bookscreate/about/?ref=page_internal

Quoted from Books Create Australia’s Facebook page:

“The Australian government has set an agenda to boost competition and encourage innovation by recommending changes to the way books are published that will put the local book publishing industry at risk.

Cheaper books sounds good … but at what cost to writers, culture and jobs? The unproven economic model suggested by the Productivity Commission does not guarantee cheaper books. Is the chance of getting 10% cheaper books worth it?”Key Issues:

1. Term of Copyright: recommended to change from death + 70 years, like the US and UK markets to 15 – 25 years from publication.

— This means anyone can publish a book that is pre-2001 without the person who wrote its involvement. Think Man Book Prize winners, like Peter Carey’s ‘True History of the Kelly Gang’, Tom Keneally’s ‘Schindler’s Ark’ and Stephanie Alexander’s ‘A Cooks Companion’.

2. Parallel Importation Rules: recommended to be abolished.

— Australia would no longer be playing on a level playing field. We would give away intellectual property rights without gaining any reciprocal rights with the world’s biggest book-creating nations – the USA and the UK – that maintain their own home market rights. Holding Australian rights to publish a book is the basis on which publishers invest $120M per annum in our local economy by partnering with and paying authors, hiring staff, printing and marketing books.

3. Fair use: recommend US-style fair use to enable large enterprises, including ISPs and educational institutions to use book content for free, without rewarding creators.

— Would we expect a desk and chair manufacturer to provide furniture for classrooms for free? This change has the potential to destroy Australian education publishing. How will it be viable to produce content?”

#bookscreate ideas

#bookscreate culture

#bookscreate innovation

#bookscreate jobs

#bookscreate futures

#bookscreate Australia

Not long after I sold the rights for The Birdman’s Wife to Affirm Press, I was delighted to be offered a publishing contract from Wavesound, a new audiobook imprint dedicated to making Australian titles available in alternative formats to print. Wavesound is an imprint of Audible, the world’s largest publisher of audiobooks. All of Wavesound’s audiobooks are recorded locally in Sydney, and employ Australian actors.

Not long after I sold the rights for The Birdman’s Wife to Affirm Press, I was delighted to be offered a publishing contract from Wavesound, a new audiobook imprint dedicated to making Australian titles available in alternative formats to print. Wavesound is an imprint of Audible, the world’s largest publisher of audiobooks. All of Wavesound’s audiobooks are recorded locally in Sydney, and employ Australian actors.

I’m a slow writer. Fast, when I have the idea sorted out, be it the outline, the chapter, the character sketch, but in the lead up to these flurried bursts of keyboard tapping, there are months, weeks, years – Toni Morrison calls it ‘playing in the dark’ – of uncertainty and unease. The requirement of much patience, of inventive healthy (and no-so much), antidotes to that humming motor of anxiety. What surprises me, over and over, are the number of possibilities for the next big project that need to be sifted through before I can settle upon the one that has all of the required parts.

I’m a slow writer. Fast, when I have the idea sorted out, be it the outline, the chapter, the character sketch, but in the lead up to these flurried bursts of keyboard tapping, there are months, weeks, years – Toni Morrison calls it ‘playing in the dark’ – of uncertainty and unease. The requirement of much patience, of inventive healthy (and no-so much), antidotes to that humming motor of anxiety. What surprises me, over and over, are the number of possibilities for the next big project that need to be sifted through before I can settle upon the one that has all of the required parts.![160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca[1][1]](https://melissaashley.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/160bcdabb99fe24ca648c273a751d9ca11.jpg?w=274&h=361) I do think the memoir project is a keeper, though not for now. The on-the-road jag is dead to me. But the novel of the Sun King and the Old Regime, keeps flashing in the peripherals of my daily life; as I fall asleep, as I drive, drinking a glass or wine (or two), reading my students’ drafts, such that I’m going to give it a chance. I’m saying yes to its long courtship. For it has everything and more to keep me occupied, entertained. After a long wait, I’m thrilled to be back to my desk, the agony (I do not exaggerate) of midwifing my first novel forgotten, eager to fill in some new blanks.

I do think the memoir project is a keeper, though not for now. The on-the-road jag is dead to me. But the novel of the Sun King and the Old Regime, keeps flashing in the peripherals of my daily life; as I fall asleep, as I drive, drinking a glass or wine (or two), reading my students’ drafts, such that I’m going to give it a chance. I’m saying yes to its long courtship. For it has everything and more to keep me occupied, entertained. After a long wait, I’m thrilled to be back to my desk, the agony (I do not exaggerate) of midwifing my first novel forgotten, eager to fill in some new blanks.

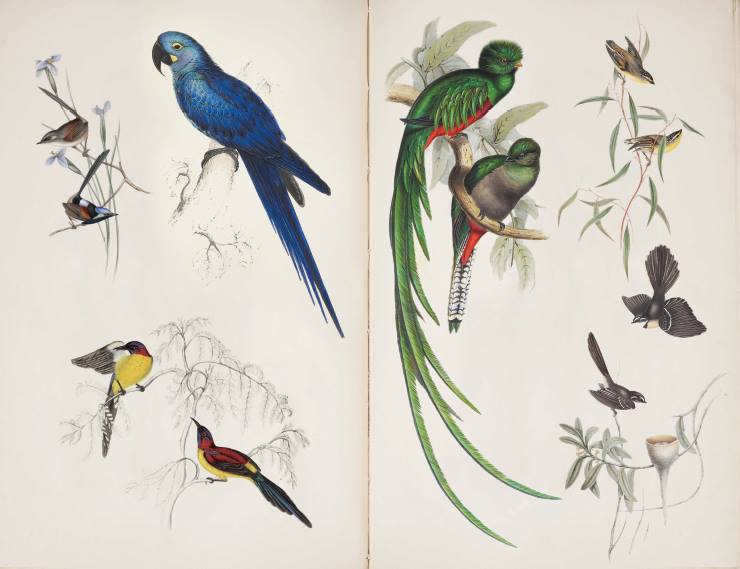

Elizabeth Gould was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover and helpmate to a passionate and demanding genius, and as a devoted mother who gave birth to eight children. In a society obsessed with natural history and the discovery of new species, Elizabeth Gould was at its glittering epicentre. Her artistry breathed life into hundreds of exotic finds, from her husband’s celebrated discoveries to Charles Darwin’s famous Galapagos Finches.

Elizabeth Gould was a woman ahead of her time, juggling the demands of her artistic life with her roles as wife, lover and helpmate to a passionate and demanding genius, and as a devoted mother who gave birth to eight children. In a society obsessed with natural history and the discovery of new species, Elizabeth Gould was at its glittering epicentre. Her artistry breathed life into hundreds of exotic finds, from her husband’s celebrated discoveries to Charles Darwin’s famous Galapagos Finches. Fired by Darwin’s discoveries, in 1838 Eliza defied convention and her own grave misgivings about leaving all but one of her children behind in London in the care of her mother by joining John on a trailblazing expedition to the untamed wilderness of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales to collect and illustrate Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.

Fired by Darwin’s discoveries, in 1838 Eliza defied convention and her own grave misgivings about leaving all but one of her children behind in London in the care of her mother by joining John on a trailblazing expedition to the untamed wilderness of Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales to collect and illustrate Australia’s ‘curious’ birdlife.

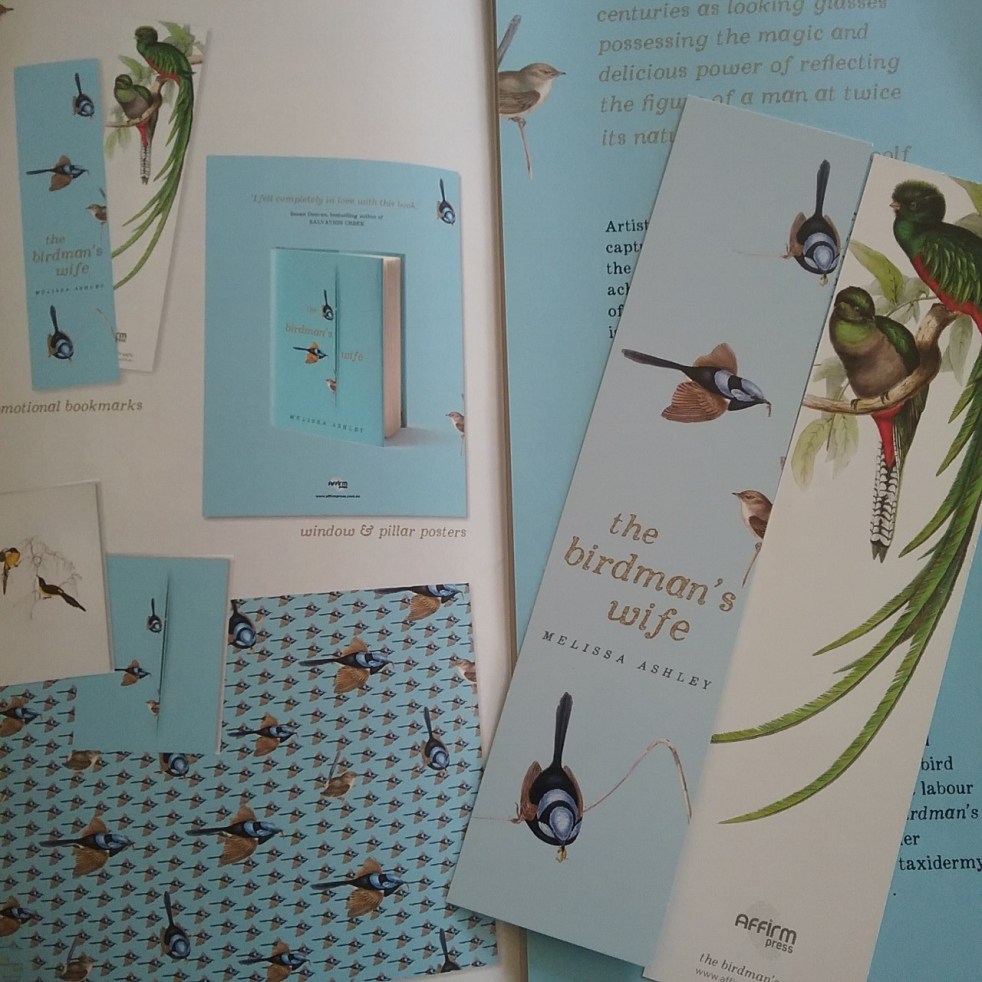

My dream for more than a decade, was to have a novel published. I am very fortunate to have signed with Affirm Press, who have worked tirelessly — many, many thanks to Christa Moffett, Karen Cook, Kathryn Lafferty and Fiona Henderson — for all the work you have put into finding, funding and designing these exquisite endpages featuring the artworks of Elizabeth Gould. (The indigo macaw is Edward Lear’s.) I could not be more pleased and excited!

My dream for more than a decade, was to have a novel published. I am very fortunate to have signed with Affirm Press, who have worked tirelessly — many, many thanks to Christa Moffett, Karen Cook, Kathryn Lafferty and Fiona Henderson — for all the work you have put into finding, funding and designing these exquisite endpages featuring the artworks of Elizabeth Gould. (The indigo macaw is Edward Lear’s.) I could not be more pleased and excited!