The Booktopia Book Gurus asks Melissa Ashley Ten Terrifying Questions

1. To begin with why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself – where were you born? Raised? Schooled?

I was born in New Zealand and at 7 years of age moved to Australia with my parents and siblings. We lived in Sydney for a short while, and then moved to Brisbane. I was moved around a lot as a child, attending more than 10 schools, and living in the same number of houses.

I think, in a way, this has helped me as a writer. It’s given me a sense of impermanence and adventure. A deep knowledge that there are many lives to be lived. And to not ever get too comfortable.

I glance back at my freewheeling childhood with a big grin, a wash of guilt and a bit of a shudder.

It was a mad blur of adventure: hanging out unsupervised near waterholes; burning around the neighbourhood on our 10 speed racers and BMX bikes sans helmets and sunscreen; riding go-carts down a street known as ‘killer hill’; jumping from the roof of the lower storey of a friend’s home into the swimming pool. We told ghost stories on the school oval and believed in aliens and spontaneous human combustion. We read Trixie Belden and Sweet Valley High and Judy Blume’s Forever.

Someone was always falling off their bike or skinning their knee – but we just got on with it. A scab or signed cast was a badge of courage, honour, pride.

2. What did you want to be when you were twelve, eighteen and thirty? And why?

When I was twelve I wanted to be a journalist. My lovely father bought me software for our brand-spanking new Commodore 64 computer – The Newsroom I think it was called – with templates and clipart to produce a broadsheet type document. And so I started writing a newspaper for our neighbourhood. It lasted a sum total of two issues and was called ‘The Aussie Informer.’ It was only years later that I cottoned on to why my mother suggested I try a different title.

At eighteen, fascinated by altered states, mysticism and psychosis, I decided my future lay in psychology. (I did some strange reading in grade 12 holed up in my bedroom playing Disintegrationby The Cure over and over.) I completed a double major in psychology as my undergrad degree but after a year volunteering at Lifeline, realised I was not cut out to be a counsellor.

At 30, I came to the end of my short career as a poet. My only book of poetry, The Hospital for Dollswas published around this time. For years I had believed that unless I had my first book out by 30, I was somehow not a REAL writer. But it was at 30 that I decided that fiction was for me. The lines of my poems kept getting longer and longer and suddenly they were blocks of prose. And I hung around too many real and talented poets to kid myself indefinitely. So I unlaced my poetry Doc Martins and began writing my first novel.

3. What strongly held belief did you have at eighteen that you do not have now?

That I knew it all!

4. What were three works of art – book or painting or piece of music, etc – you can now say, had a great effect on you and influenced your own development as a writer?

I love Bernini’s sculpture The Ecstasy of St Teresa; it’s in a little church in Rome. The very cheeky psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan once suggested that the expression on the saint’s face, rather than showing her overtaken by mystical bliss, was actually more mundane: she was having an orgasm. In high school, my artistic sister drew a wonderful detail, in stipple of St Theresa’s thrown-back head, and this made it stick in my mind. Travelling in Rome in my early 20s, I sought out the church in which the sculpture lived and was brought to tears. My love of its beauty has only deepened over the years.

Anne Sexton’s signature poem Her Kind, about being a female writer whose weird talent and uncertain social position makes her identify with witches. ‘I have gone out, a possessed witch’. Anne Sexton was a bewitching woman, drop dead gorgeous, sassy and seductive and I will never forget listening to a recording of her reading Her Kind at the State Library. I was shocked beyond words by her gravelly, cold, nasal voice. Yet what power it conveyed, what experience!

I absolutely adore Ovid’s tale of Apollo and Daphne; Apollo chases the nymph Daphne through the forest, wishing to carry her off. Determined to keep her freedom, Daphne transforms herself into a tree. The motif of the nymph’s fleshy body slowly transformed into bark and leaves, her hands and arms spreading into branches, still weaves through fairy tales, poetry and literature today. I can’t fully explain it, what fate, to become a tree in the woods, but the myth has a magnetic pull on my imagination. I suppose somewhere in my understanding of the archetype, I imagine her throwing off her mantle of leaves and emerging, transformed and powerful, a woman now, in command of herself and untouchable.

5. Considering the innumerable artistic avenues open to you, why did you choose to write a novel?

To be perfectly honest, I think it was some kind of irrational madness. An obsessive determination. AsSamuel Beckett famously observed: I’m simply no good at anything else. I think writing a novel is such an incredible challenge, a journey into the unknown, developing unique relationships with characters and story, it’s agony of course, but such indescribable magic when the scene or chapter you’ve been chasing, trying to wrestle into place, suddenly falls together. There is something mysterious about writing, it’s a lesson I have to learn again and again. It is sort of the key, I suppose. It’s like making beer, or firing ceramic. You have all the ingredients, you make the product, but then in the process or heating or fermenting, a little miracle occurs. You can never tell what the finished chapter or scene will be. And maybe this is what keeps people writing. This is such an incredible reward. Something satisfying between you and the page. So deep, so private, so exhilarating.

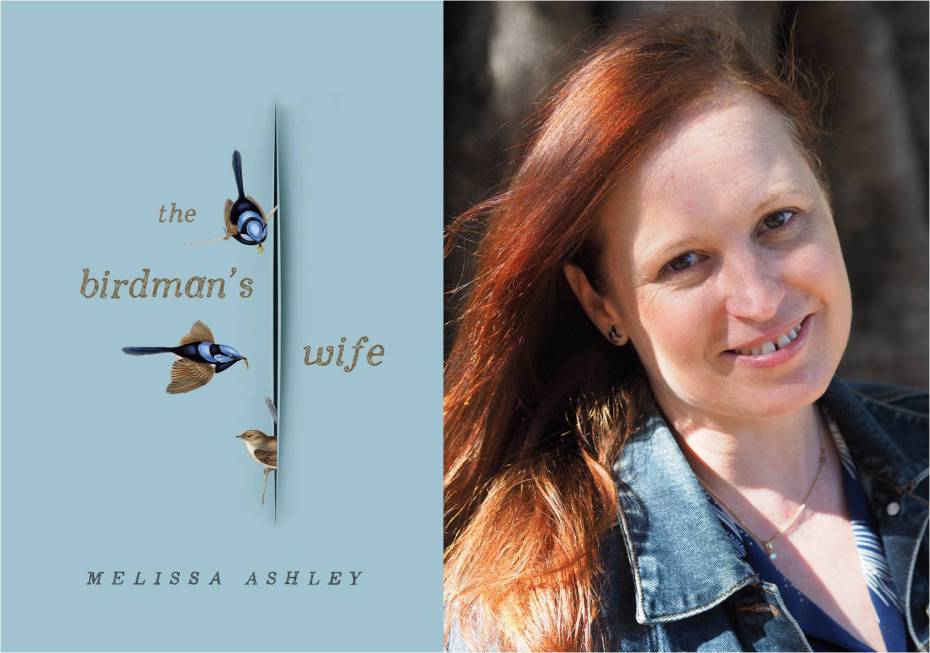

6. Please tell us about your latest novel…

John Gould, the famous 19th ornithologist known as ‘The Birdman,’ is renowned for creating the most sublime images of birds from all over the world. But few people know that his wife, Elizabeth Gould, was the artist who drew, illustrated, designed and lithographed more than 600 of the exquisite hand-coloured lithographs he produced. Yet her legacy has been overshadowed by her husband’s fame.

Elizabeth was a woman ahead of her time, juggling her work as an artist with her role as mother to an ever-growing brood of children. She was a passionate and adventurous spirit, defying convention by embarking on a two-year expedition to the Australian colonies with her husband to collect and illustrate our unique birds and plants. At a time when the world was obsessed with discovering natural wonders, Elizabeth was at its epicentre, working alongside legends like Edward Lear and Charles Darwin. The Birdman’s Wife tells her amazing story.

7. What do you hope people take away with them after reading your work?

A sense of delight and fascination – for the extraordinary woman Elizabeth was and the contribution she made by bringing to life the beauty of birds that people had never seen before – and a love of birds! A little window into the discovery of Australia’s wonderful birds.

- John Gould

- Elizabeth Gould

8. Whom do you most admire in the realm of writing and why?

It’s hard to narrow it down to one particular person. I admire writers like Stephen King and Joyce Carol Oates and Neil Gaiman who are incredibly prolific and productive. Envy really. But the writers I think I most love, are those whose imaginative worlds are rich and unique, a newly discovered planet, and life on these unique places stays with me for years and years.

Two of my favourite authors weave fairy tales into their novels: the late Angela Carter, author of The Bloody Chamber; and the wonderful A. S. Byatt, author of Possession.

9. Many artists set themselves very ambitious goals. What are yours?

I always worry about time. I’m in my forties, so I better get cracking. I would love to write a novel every three years. To publish more wonderful stories about fascinating characters. At present I’m entranced by historical fiction. But I love contemporary literature too, so who knows where the future will lead. There’s a memoir in me, I hope, I have the story, but I’m saving it for later down the track. Ah, carried away just thinking about it!

10. What advice do you give aspiring writers?

Don’t worry about your ‘natural talents’. Try not to think about time overly much. I have come to believe that one of the most important qualities of a writer is patience. Whether emerging or developed, the need for it never goes away. Keep trying, keep learning. Embrace criticism and feedback. Keep reading! At the end of the day, becoming a writer, continuing to write, making it a career, is about putting yourself forward, about not giving up. Tenacity. Determination. And lots and lots of writing and revising.

Thank you for playing, Melissa!

by Anastasia Hadjidemetri |October 7, 2016